Darkness of Unknowing

On Joy Williams' "99 Stories of God"

For now we see through a glass, darkly; but then face to face: now I know in part; but then shall I know even as also I am known. - 1 Corinthians 13:12

Had Joy Williams titled her collection, simply, Ninety-Nine Stories, it might have quietly but confidently found itself a comfortable place, perhaps alongside Donald Bartheleme’s Forty Stories, in the umbrellic shade cast by Salinger’s Nine Stories—for many the platonic ideal of American short fiction. But she did not. She named it Ninety-Nine Stories of God, and went off in a bewildering new direction.

Williams understands the power of a title. In fact, the titles trail the stories in this collection, capping off her strange microfictions, often in ways that recontextualize everything that came before.

On God

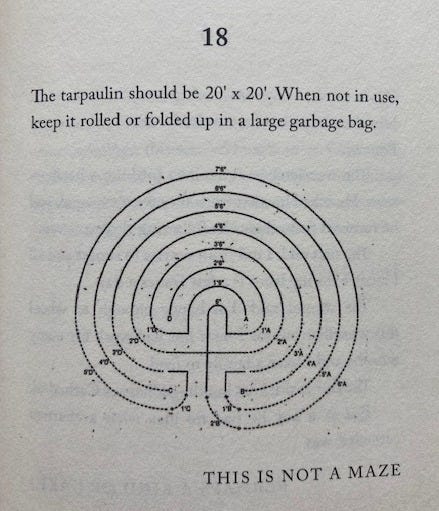

Invoking God in the collection’s title recontextualizes everything between its covers, challenging the reader to root out God in each of its ninety-nine tales while knowing full well that the word “God” carries with it amongst the least consensual reality of any word in the English language. A story that might move one reader to tears could, for another reader, be, just as deeply, unreadable blasphemy. According to the majority of reviews I came across, however, these stories largely just confounded readers, left them cold and/or confused. One Goodreader complained that, in reading, they “felt no connection to God”, which is partially by design. The book does not give readers much by which to orient themselves. It does not even include page numbers! Enter into it expecting a maze to be solved and you will only walk in circles until you arrive at a dead end. There is no map for the spiritual path, and the God we are dealing with here is no white-bearded cop in the sky, but something closer to Meister Eckhart’s conception of the Godhead.

In his book, Religion and Nothingness, Zen philosopher Keiji Nishitani breaks down what Eckhart means by the Godhead as “the point at which all modes are transcended.” Here “all modes” includes even the divine. For Eckhart, Creator is the form of God that is bared to creatures and seen from the standpoint of creatures, but it is not to be taken as what God is in himself, as the essence of God. As such, union with God does not take place with the Creator, but upon the Godhead, which is “not a never-never land” or a self-intoxicated isolation, but something closer to the Buddhist conception of śūnyatā, or the Emptiness at the root of being, and it is to be encountered in the practical activities of everyday life.

For Nishitani, union with God cannot occur through direct contemplation of God because God is beyond all intellectual understanding. It occurs in the Realization (and here Nishitani uses the word with two-pronged meaning: both understanding and making-real) within everyday life of the Nothingness of the Godhead.

But perhaps we are getting a little ahead of ourselves here. Until now, Gnostic Pulp has largely dealt in household names, insofar as any writer can make such a claim in these illiterate days. Joy Williams is not exactly obscure, but she is less a known quantity than the likes of Melville, PKD, Pynchon, and Ursula LeGuin, but this humble Substacker would put her on par with these, and any other name in the roster of American letters. Although, to be fair, I did not come to her through Ninety-Nine Stories. Had I, the collection may have left me somewhat cold as well, for it is undoubtedly a difficult nut to crack.

Upon my third and latest read, I approached the collection with a plan. Despite story #49’s warning, that we should not “define God in human language”, I devised a chart by which to subdivide the ninety-nine stories into categories. Although the collection kicks off with a bonafide miracle, presented without explanation, such stories (which I labeled “Extraordinary Events”) make up only ten percent of the collection.

By far, the majority of stories are what I call “Matter of Fact”, in which nothing discernibly extraordinary happens. That is, while any matter of exciting events may transpire, up to and including murder, nothing impossible to explain within the usual limits of reason takes place. Such stories take up half of the assemblage. The next most populous category is what I called “Artist at Work”, in which a famous artist, mystic, or, yes, even in one case, the Unabomber, act as a story’s prime interest.

Following closely behind, is “The Lord”. These are stories in which, you guessed it, The Lord is the protagonist. Next is “Extraordinary Events”, then “Theology”, and finally “Story Within a Story”, but let’s just show you the chart:

Lesley Jenike, writing in Ploughshares, offers the most piercing glimpse into this collection of any I came across. She identifies the second story, Noche, as a sort of skeleton key. Noche includes the two most prominent images in the Williams mythos: sunglasses and German shepherds. A Tarot card featuring Williams would be incomplete without these two pieces of imagery.

The story concerns a breeder of German shepherds who advertises herself as being from Sedona, “a place known far and wide for its good vibrations, its harmonic integrity,” but who, in reality, operates out of nearby Jerome, a former copper mining site now staving off total ghost town status by mining out its own history for tourism dollars. The town’s main claim to fame seems to be the 1917 Jerome Deportation, in which, following a period of labor unrest, 60 suspected members of the IWW were rounded up by armed vigilantes, loaded onto cattle cars, and “sent west” (Jerome, Arizona).

“In any case, the dog coming from Jerome rather than Sedona was telling, people thought.”

Although we are never actually given any insight into the dog’s behavior, which is implied to be in some way unsatisfactory, an explanation for it is offered: the fact that its owner wears sunglasses, day and night, indoors and out. “The dog never got to see her eyes.” Not only that, but the owner puts out a bowl of sunglasses anytime she has company over and has everyone dawn a pair so that the dog never gets to see anybody’s eyes.

“Joy Williams in her sunglasses might be a walking metaphor. It occurs to me that in Williams’ world, God is also wearing a pair of mirrored sunglasses, and after we tire of making funny faces at ourselves in His lenses, we start to panic. We wonder what He may be thinking, because without God’s eyes, how can we know whether or not He exists? Without His eyes, how do we know if we’ve won His approval, His fury or, even worse, His ambivalence?” (Jenkie)

Real Williams heads will, of course, think of her essay Hawk, one of her most well known and affecting pieces of writing. It is an essay in part about Glenn Gould, but mostly about Hawk, Williams’ own black German shepherd, who’d been with her since he was two months old. It is not difficult for a writer to pull the heartstrings of a dog-lover (especially one who has had his own black German shepherd since he was two months old (and is now pushing a decade!)). That much is well known. But Williams takes no cheap shots. She is a true and pure animal lover herself, a stout champion of the so-called natural world, and she writes briefly and honestly of her life with Hawk in a way that swells the heart. “I loved Hawk and Hawk loved me. It was the usual arrangement” (155). But eventually Williams takes sick and must kennel Hawk while attending to her own health. She takes him to a boarder where he has been before, and just as she is saying goodbye “he turned and looked at me and rose and fell upon me, seizing my breast. Immediately, as they say, there was blood everywhere…Hawk! I kept calling my darling’s name, Hawk!” (158).

In the course of things, Hawk has to be put down. He has changed and is no longer the same dog. There is never any clear indication of what happened. The owner of the kennel says brain tumor, but Williams’ vet does not think so. Why does the white whale tear off Ahab’s leg? Why does Hawk turn on his loving owner? There is no answer. “Something unspeakable and impossible and calamitous had happened” (163). It is this same inscrutability that haunts the ninety-nine stories here gathered.

Lord Help Us

The Lord is featured in fourteen of the ninety-nine stories, and, though He is immediately likable, He comes off more as a bumbling fool than an all-powerful creator. He is presented as aloof, confused, and disappointed. He prefers the company of animals to the world of men even though the animals would rather not have Him among them, and beg Him to spend more time among the species who is ravaging the planet, believing, perhaps, His influence would have some effect.

“But the Lord said He was lonely there.”

What are we to make of this God who in story #93, in a conversation with a pack of wolves, mourns the fact that human sentiment is set so much against them? He offers to take from them their taste for cattle, but the wolves appear wiser than Him and counter that it wouldn’t matter. They will just be killed for some other reason. This stumps The Lord and he apologizes.

“Thank you for inviting us to participate in your plan anyway, the wolves said politely.

The Lord did not want to appear addled, but what was the plan His sons were referring to exactly?”

What can such an ineffective God be but that vision we see reflected in His sunglasses and mistake for God? The Creator severed from the Godhead, God without śūnyatā. That is to say, our ego’s reflection, mis-recognized and elevated in our imagination, so that we place ourselves atop the planet’s hierarchy, and see the rest of its creation as under our dominion. God anthropomorphized, egoized; a God created in our image. The vulgarized idea of God who is used as the reasoning for our gross overstepping, and as a cudgel by those with all-too-human ambitions against the vulnerable. A sort of tulpa God.

How can such a figure, well-meaning or not, offer any answers? He is dizzied by the climate crisis, by the contamination of His living water (#10), by the vapid wastefulness of hotdog-eating-contests (#55), by the senseless killing of roosting bats (#73), and humanity’s vendetta against wolves (#93), for at the same time He is humanity’s guilty conscious projected outwards, on some level aware of its sins and the danger our own actions are putting us in.

This is the imagined God of a humanity who cannot take responsibility for its own sins, who longs for an outside force to save us from ourselves, or at least to punish our transgressions. This is the God David Berman sings about in Margaritas at the Mall.

How long can a world go on under such a subtle God?

How long can a world go on with no new word from God?

See the plod of the flawed individual looking for a nod from God

Trodding the sod of the visible with no new word from God.

This desire to do nothing but drink margaritas at the mall while waiting for God to save humanity from its self-inflicted problems is the same as our frozen response to Nietzsche’s Dead God hypothesis. Indeed, Williams hints towards Nietzsche with the final sentence of the book.

In story #99, The Lord is visiting a psychic in Maine. She is struggling to see Him, and starts throwing out lines she reserves for her more difficult clients. Nothing works, so she skips ahead to the question, she believes, everyone has.

“What’s going to happen after I’m dead?”

What’s going to happen after The Lord is dead indeed? Throughout his fourteen appearances, other characters seem to be waiting for Him to do something, but this serves only to confuse Him. He is simply not going to do anything. It is not in His nature. He does not even know what Plan it is that his children are referring to.

Morning Dew

Nietzsche’s God is dead makes quite the effect when written in black against the blank of a whiteboard in a high school English class on the first day of the Introductory Existentialism segment. It does what a hot take is meant to do. It gets people talking. Riles em up on both sides, but it also gets woefully misused.

There can be little doubt that the God-as-understood-by-pre-Nietzsche-Christian-Europe is dead, the God by which people oriented their lives, understanding the universe down to its very physical mechanics through His light. The all-powerful, moralizing, interventionist God, of whom we were His preferred children, is dead. Nietzsche did not mean this as a gloat. He meant it as a statement of reality. Society no longer structured itself upon such a belief, people could no longer access it in the same way, and we had to find a way to move forward, which meant some new source of meaning had top be located.

The final story ends before the psychic answers her own question. Nothing follows but the title, The Darkling Thrush, which is derived from a poem by Thomas Hardy, originally titled By the Century’s Deathbed. The poem tells of a narrator going out for a walk on a desolate winter day. The world is described as “spectre-grey”, compared to a corpse, the wind is a death lament. This seems very much the world in which God has died and humanity sits frozen, in which the climate crisis explodes while we do little more than drink margaritas at the mall, or seek “houeshold fires”, and remain trapped in our vain vision of ourselves, the world as our dominion, all her natural booty to be sucked up by the mechanisms of Capital; shit’s fucked, in other words.

Hardy’s narrator sees no hope. If God is dead then the world is dying. He is like a character out of one of the “Matter of Fact” stories in this collection: confused, living life at a remove. But then a thrush, old and beaten up, breaks into a “full-hearted evensong of joy illimited” and the narrator must admit there might be some blessed Hope of which this bird is aware and he is not. The reflected and projected God might be dead, but the thrush still finds reason to sing. The dew still accumulates upon the grass in the morning whether it is described in scientific language or as a gift from some benevolent Father-God.

The thrush is singing not beside the pain of the world, but from within it. The two, beauty and pain, are mixed, absolutely. In Buddhism, Dukkha is a part of the First Noble Truth. It is sometimes defined as suffering, but, more precisely, it is the suffering that is derived from wishing that things were otherwise rather than accepting what is. While pain and discomfort cannot be transcended, Dukkha can.

I wish I could have this bird singing without this desolate winter.

But it is against the backdrop of the desolate winter that the thrush’s song stands out and is made beautiful. They are not opposite, but inseparably mixed. Ditto for the miraculous and the mundane, heaven and earth, eternity and time.

If this collection contains, as it claims, Ninety-Nine Stories of God, then God must be present in each one, but if we have been mistaking our own reflection for God, then who or what is behind those mirrored glasses? And might some relation with this realm of being save us from ourselves?

This is the God of Eckhart and the mystics who appear throughout the text, from Simone Weil to Philip K. Dick. The God we come to not by projecting an image of ourselves, but by negation, not via contemplation, but through a vision in a flash of light. This God cannot be defined in human language, nor spoken of rationally; this God can be met not through the accumulation of knowledge, but via negative theology, seen only through a cloud of unknowing, as we “push our minds to the limits of what we could know, descending ever deeper into the darkness of unknowing.”

The singing thrush, the light off a pewter plate, an offhand comment by the courier bringing pain meds after dental surgery, these are the exact kind of innocuous events that, in Zen koans, lead to enlightenment. In this light, it was the “Extraordinary Events” and “Matter of Fact” stories that became the most difficult to parse. At times it seemed any could have gone either way.

[Exit Music]

Love the reference to Keiji!

I remember simultaneously loving and being baffled by this book - somehow this was my first of hers and completely sold me on her (I still think about #61 MUSEUM almost daily - “We were not interested the way we thought we would be interested.”). I have yet to get to last year’s sequel? follouwup? Concerning the Future of Souls: 99 Stories of Azrael, but it’s been on my shelf staring at me for months so maybe now’s the time.

Also curious about the parallels between this style of Joy Williams stories and the other bonkers micro-short stories of Diane Williams, which feel sometimes as thematically similar but completely unmoored from any sort of reality in a way Joy W’s are not.