The ultimate fate of Stephen King’s legacy is a question that gets bandied about on book forums from time to time. The discourse is about as interesting as it sounds, but that the question arises should come as no surprise, for King occupies something of a singular place in ~American Letters~ and has for a long time: a living writer whose name you can throw out in almost any company with a fair degree of certainty that it will be recognized.

If we have a household name, it is King.

And really, there could be no one better suited to the role. I don’t mean to disparage the man’s work here, but he is a perfect distillation of the last half century of American cultural production: he publishes far too much (65 novels and 200 short stories), and too often (an average of 1.3 books per year since his debut in 1974) for a new release to make a splash in the greater cultural sphere, and yet, like the drooling lords of our gerontacracy, he just won’t go away; his best-loved works are nearing the half-decade mark; and he is aging into an increasingly insufferable Bluesky guy.

But none of this is what I meant to get bogged down with. While I’m no aficionado, I have read and enjoyed several of King’s books. Hell, I’ve even taken a selfie in front of his house.

There’s no denying he is a more-than-respectable literary craftsman. No doubt he is a gifted storyteller with a real talent for ratcheting up suspense, a solid grasp on human psychology, and a good ear for regional dialects.

However his ultimate legacy turns out is a matter for future generations. I’m just here to talk about a ghost story.

Cucked by Kubrick

In anticipation of a summer visit to Rocky Mountain National Park, I decided to read The Shining, which is famously inspired by a trip the author took to the region in the mid-70s. As Connor Randall, co-star of Hellier and former paranormal investigator for the Stanley Hotel, tells it, King and his wife, Tabitha, did not intend to stay a night in Estes Park, but they were surprised by a seasonal road closure en route to Grand Lake and were forced to turn around. All that extra driving landed them in Estes Park near nightfall and they needed a place to stay. Was it happenstance that that place ended up being room 217 of the Stanley Hotel on the very last day of operation before closing down for the winter, meaning the couple were the hotel’s only guests?

All you rational readers of the age of science may say yes, of course, but I cut my teeth on LOST so I know that certain localities call out to certain personalities.

Even before King made it famous, the room had a reputation thanks to a 1917 incident in which the hotel’s chief housekeeper was lighting the acetylene lanterns. In 217, the lamp exploded, blasting out the ground from beneath her feet, and landing her on the floor below, whereupon she broke both ankles. Guests ever since have been reporting a visiting spirit with a knack for tidying up— but wait, you may be saying. She didn’t even die. How could there be a ghost? To which I say, oh my sweet secular child and your infantile understanding of eidolonic potential.

While there are no reports of King experiencing anything paranormal during his stay, he did dream of his young son being chased through the hallways of the hotel by a fire hose. He awoke from the nightmare and smoked a cigarette. By the time he turned back in for the night, he had the overarching idea for The Shining sketched out.

The novel was published in 1977, three years after the Kings’ stay at The Stanley. Three years after that, another Stanley would come to haunt Stephen King, Mr. Stanley Kubrick, whose adaptation of the novel the author famously hated.

The film is an all-time classic of the horror genre. It is beloved by snobs and plebs alike. I have a particular soft spot for it because it was the first movie Amy (my wife) and I ever watched together. But King, who was passed over for the screenwriting position, hated the adaptation.

“That’s what’s wrong with The Shining, basically…the movie has no heart; there’s no center to the picture. I wrote the book as a tragedy, and if it was a tragedy, it was because all the people loved each other. Here, it seems there’s no tragedy because there’s nothing to be lost.”

It seems King’s major beef is with the portrayal of Jack Torrance. The novel offers a deeper look into the patriarch’s background, his brief literary success, his alcoholism, his fall from grace, and his seasonal job as the caretaker of The Overlook as his one chance at redemption. Throughout the novel he struggles with his genuine desire to be a good husband, father, and artist, and his fits of rage and overwhelming need to disappear into a bottomless pitcher of martians (which, after reading this book, is the only way I will be referring to martinis).

These urges are preyed upon by the darkly seductive presences within The Overlook who, over the long winter, sink their hooks deeper and deeper into Jack’s weakening flesh, making him a victim of cosmic forces. In Kubrick’s adaptation, from the moment he appears on screen, Mr. Torrance barely manages to conceal the horrifying psychopathy creeping just beneath a smile learned from the bug-alien-pretending-to-be-a-human-in-Men-in-Black:

In the end, King’s reaction is totally understandable. He’d made a piece of art he was not only proud of, but felt personally attached to in a deep way, as writing the novel was also a form of exorcising his own struggles with alcoholism. It’s out in the world and doing quite well. Then a demigod like Kubrick comes along and takes it and makes it his own.

Touch luck.

The Overlook

Stephen King loves wordplay, so of course the line"sometimes human places, create inhuman monsters" reappears later as “this inhuman place makes human monsters.” Both feel true in regard to The Overlook Hotel, the fictionalized Stanley which appears in the novel.

Hotels are already infused with strange psychospheres. They are transient places, dare I say…liminal. Just the type of place George P. Hansen writes that Trickster is attracted to in his The Trickster and the Paranormal:

“The central theme developed in this book is that psi, the paranormal, and the supernatural are fundamentally linked to destructing, change, transition, disorder, marginality, the ephemeral, fluidity, ambiguity, and blurring of boundaries” (22).

King simplifies this thesis:

"Every big hotel has got a ghost. Why? Hell, people come and go.”

People are in a different mental state when they stay in a hotel. They are away from the stability of home whether for work, vacation, or some other purpose. They might be away from their families and loved ones, meaning they feel vulnerable or maybe free of inhibitions. All this leaves them more open in general.

Add to that the particular situation of this specific hotel which is not even functioning in the purpose it has been built. It is closed for the season, so housing no guests except for the Torrance family. Not only that, but it is a luxury hotel which has seen its fair share of big ticket scandal. There have been murders covered up. There has been adultery (and probably far worse). Sketchy money deals. And maneuverings of the geo-political nature. All this is hushed up. Brushed under the rug. Just as the foundation of the hotel, and the country it stands upon, is quietly built upon the blood-soaked ground of genocide. The Overlook, and its caretaker, are haunted by their violent pasts, and their inability to integrate their shadows.

Furthermore, in The Shining, liminality is not limited to the impermanent nature of hotels. It proves a central theme of the novel. There is the hotel, as we’ve said, already transitory in nature, and now closed for the winter. Jack himself is a dry alcoholic. He and his wife, Wendy, are in something of a limbo between marriage and divorce. Danny, their clairvoyant son, is on the cusp between early childhood and adolescence. He also has the ability to blur the boundaries between inside and out with his sensitivity towards others’ thoughts and emotions. This power, the breadth and range of which remains somewhat opaque, is named the Shining by Dick Halloran, the hotel’s chef, and fellow precog, who meets the Torrance family on the day they are moving in and he is packing up for sunny Florida.

“I think a lot of things happened in this particular hotel over the years…and not all of them was good,” he warns Danny after acknowledging he, too, has the gift.

As we hinted above, the word ghost is something of a catchall for a whole range of possible cross-veil activity. What Halloran is talking about here sounds like a residual haunting. Residual hauntings are created by repetitive or traumatic events.

When someone burns toast, a smell lingers.

Call it what you will, but some kind of energy is imprinted onto the locale which will then loop this imprint mindlessly, like a tape reel. A figure might be seen from the corner of the eye, moving down a hall then disappearing: the function of the hallway has become manifest. A room that hosts parties might carry with it the distant sound of laughter or music. A corner that has held a television for decades might emit a few lonely notes from the I Love Lucy theme, or a flickering, black and white shade.

In the case of a traumatic event, a sort of bad energy might be blasted into the atmosphere, leading to the most popular cop out for people who are asked whether they believe in ghosts:

Well I’ve never seen one, but I have felt things…

The first house Amy and I lived in together was a tiny, blue place tucked back in the woods on the outskirts of a historic neighborhood, for which we paid $800 a month in rent. By day, it was a cute spot, secluded in a grove of oaks, with a big front porch and huge backyard visited by deer. But at night something came over the place. It was as if it was invaded, and not just by the scorpions our cat did battle with, evidenced by the dead bodies we’d find scattering the hallway each morning. More than that, there was a feeling of fear.

We didn’t often broach the subject when we lived there, but neither of us was willing to leave the bedroom at night, no matter how thirsty we might become or how our bladders might strain. There was something immensely unsettling just the other side of the door into whose terrain we dare not step.

After moving out, Amy discovered her co-worker had lived in the same house some years prior, and she shared with her the dark story of its history. There’d been a murder there back in the eighties. A wife discovered her husband was cheating and smashed his head in with a landline while he was taking a bath, or so the story goes.

Now, besides the validity of this apocryphal event, another question remains: was it this act that spawned the haunting and gave the house its uninviting atmosphere, or did this atmosphere exist prior to the murder and, in fact, aid in its enactment?

My poor man’s understanding of Deleuze and Guattari’s Anti-Oedipus kicks in here and I can’t help but think of ghost hunting in its popular form as some type of Oedipalization. Something unseen causes fear and we want to define it and therefore conquer it. The type of paranormal investigation as exhibited by the aforementioned Connor Randall and crew in shows like Hellier is quite different from this. Rather than force their theory onto a case, the investigators allow an unfolding to occur, and in so doing unlock an opportunity for paranormal investigation as Spiritual Practice.

gets at this idea from a slightly different angle in his recent piece in which he triumphs recontextualizing problems as games, as if our universe is inherently playful. There is a Trickster germ in the fabric of reality. One ignores this at their own peril.“Work = usefulness, extrinsicality, adultliness

Play = uselessness, intrinsicality, childliness”

I suspect this is the reason pets and children are the first to sense invisible presences in the movies. It is precisely because they do not attempt to triangulate them, but rather allow them to express themselves. This is why Danny is more attuned to the situation in The Overlook than either of his parents. It is us adults who are blind to the things we cannot give a name. We refuse to validate undeniable feelings without something to tie them to. Thus, the terrible story of the murder in our little blue house brought almost a sigh of relief. Finally, we had an explanation, and could lay the case to bed…as if it had solved anything.

Snake Stamp on the Monkey Brain

Fear seeks form. That is why scapegoating is so easy. We are all afraid of ineffable abstractions, yet our minds are hardwired to seek patterns. Some studies suggest we can detect snake images even before subjective visual perception,1 meaning we feel fear before we see the snake. With a little Kingian wordplay, we can get to: we feel fear, so where’s the snake?

It should come as no surprise that The Overlook, like The Stanley, contains plenty of ghosts with full back stories: the woman in the bathtub in room 217 is the ghost of a woman who died there. Delbert Grady, the caretaker who precedes Jack Torrance, went crazy and killed his family with an axe, and thus haunts the grounds. One gets the feeling, however, that there is something behind these forms, that something is puppeteering their shades, using them only because that is what one might expect to be hanging around a haunted hotel.

A common complaint I came across in reading reviews of the novel and the film is that the nature of the horror could not be explained. One such review made a rather astute comparison to Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) and The Mothman Prophecies (2002). In each of these works, it is as if the locality itself is sinister. Algernon Blackwood’s 1907 story, The Willows, is another entry in this genre of haunted space. In this strange tale, a couple of canoers happen upon a willow grove while paddling the Danube. They set up camp there, and quickly come to regret it.

“We had ‘strayed’…into some region or some set of conditions where the risks were great, yet unintelligible to us; where the frontiers of some unknown world lay close about us. It was a spot held by the dwellers in some outer space, a sort of peep-hole whence they could spy upon the earth, themselves unseen, a point where the veil between had worn a little thin. As the final result of too long a sojourn here, we should be carried over the border and deprived of what we called ‘our lives,’ yet by mental, not physical, processes. In that sense, as he said, we should be the victims of our adventure—a sacrifice.”

This dispersed quality is a trademark of Trickster whose circumference is said to be everywhere, yet his center nowhere. Those who do become ensnared in one of his more sinister games might be best off trying to laugh it off and walk away, else you be beckoned to come play with us…forever.

An investigation into such matters only invites a further ensnaring, as John Keel warns in The Mothman Prophecies:

“Paranormal phenomena are so widespread, so diversified, and so sporadic yet so persistent that separating and studying any single element is not only a waste of time but will automatically lead to the development of belief. Once you have established a belief, the phenomenon adjusts its manifestations to support that belief and thereby escalate it.”

While we are dwelling on classic stories of the weird, we would be remiss to not mention Eddie Poe’s The Masque of the Red Death as it is a bit of a motif running throughout The Shining. While it does not neatly fit into the genre we were sketching out above, it does share some things in common, especially the big reveal at the end. For those who haven’t read it, you really should. It’s not long and it’s in the public domain. Here’s a link. I’ll wait.

Now that we’re all on the same page, we know it’s the story of Prince Prospero and his rich friends hiding out and throwing a masquerade while a plague known as the Red Death runs rampant beyond the walls. But of course there is no hiding from death, and Prospero dies upon confronting a stranger who has infiltrated the party.

“Then, summoning the wild courage of despair, a throng of the revellers at once threw themselves into the black apartment, and, seizing the mummer, whose tall figure stood erect and motionless within the shadow of the ebony clock, gasped in unutterable horror at finding the grave-cerements and corpse-like mask which they handled with so violent a rudeness, untenanted by any tangible form”.

Following this startling revelation, all the remaining revelers drop dead. And the life of the ebony clock goes out. The evil has no source, no form. It is embedded in the very fabric of reality, as if we are living in a expressionist universe. They played the game, but underestimated their opponent, and forgot the most important rule: every game is sacred. One must dress themselves in the garb of The Magician in order to stand toe-to-toe with Trickster.

The Clock Goes Out

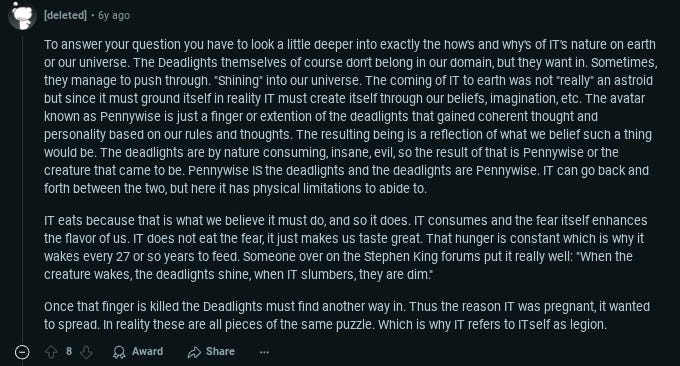

In the overarching cosmology of the Kingverse, as fleshed out most directly in The Dark Tower series, Gan is the supreme creative force of the multiverse of whom little is known beyond the fact that he arose out of a primordial chaos known as the Prim, and that he created Maturin, the turtle, who is a manifestation of wisdom, kindness, compassion, and order. But Gan also created The Deadlights, who manifest on Earth as Pennywise who is about the opposite of all that the turtle stands for. Pennywise, the clown of IT was never human, but is instead a shapeshifter who is billions of years old and has its origins outside of the known universe. This unknown Reddit user sketches it out quite well:

In The Shining, Jack, a man with a rocky employment history looking to make good, is strung along by a promise that The Manager is interested in him. That hook is like his personalized invitation into the sewer. The Manager is never seen directly, but is felt to be ever present, the genius loci of The Overlook, encouraging Jack along. He begins to investigate The Overlook, going against John Keel’s advice. Jack, sad to say, is no Magician. Unlike his son, he has no tools with which to combat Trickster’s invasion, so his investigation only mires him deeper in the snare that has been set by The Unknown.

And by The Unknown, we are not here speaking of a mystery that might be solved if not for lack of evidence, but rather The Unknowable. Something that is beyond human understanding. Could it be another manifestation of The Deadlights spicing up its next meal with a healthy sprinkling of fear? Sure, okay. Maybe. But throwing around such names should provide no comfort. They no more describe the nature of the thing to which they refer than do the three letters G-O-D.

This is what makes fear so dangerous. The same fear that saved our early primate grandmas and grandpas from snake bites is still pressed deep in our biological make up, and sometimes those primitive alarm bells go off when there is no snake in sight. There are certainly unseen forces looking to take advantage of just such a scenario. Whether those forces are demonic clown-spiders from beyond our dimension, the restless spirits of the dead, repressed desires within ourselves, or those at the controls of a certain socio-economic system that thrives in an environment of fear and paranoia, a couple deep breaths and a quick evocation to the great turtle of love, wisdom, and order might be just the thing to save your ass from a bad situation.

Then again, that didn’t do anything for Danny when the lady in the bathtub was closing in. Sometimes we just find ourselves outmatched.

Good luck out there.

[Exit Music]

Ohman, A.; Soares, J. J. (1993). "On the automatic nature of phobic fear: conditioned electrodermal responses to masked fear-relevant stimuli". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 102

Good piece, very enjoyable writing. About play and children and hauntings and tricksters, and related to your passing references to the mothman movies:

My family is from Point Pleasant, West Virginia, where the Mothman stories originated. Going to visit as a kid, my parents would point out the mothman statue in the center of town. It’s this huge, terrifying metal statue with glowing red eyes and claws and evil wings and such, but I always misheard mothman as the muffin man. So i would run up and hug the mothman statue, so happy to meet the muffin man from the nursery rhyme.

Wow. You spent a lot of time and effort on this piece. I think King is responsible for warping good minds into bad minds. I used to love horror books/movies, etc - until I realized how corrosive they are to the human spirit, when they become a part of your Being. Devil worship, criminal worship, fascination with murder, death and mayhem are truly works of Satan. I mean unless you are an atheist. Just look at his political views as well. He hates Christians and Christianity I think.