In a rather panning review of Against the Day, Thomas Pynchon’s sixth novel, The New York Sun’s Adam Kirsh takes aim not only at the work itself, but at the author’s avid readers, writing “[Pynchon] fans love to apply their homemade hermeneutics to the mysteries with which Mr. Pynchon’s novels are carefully seeded.”

To which I must applaud his astuteness. Homemade Hermeneutics would have made a killer name for this here enterprise.

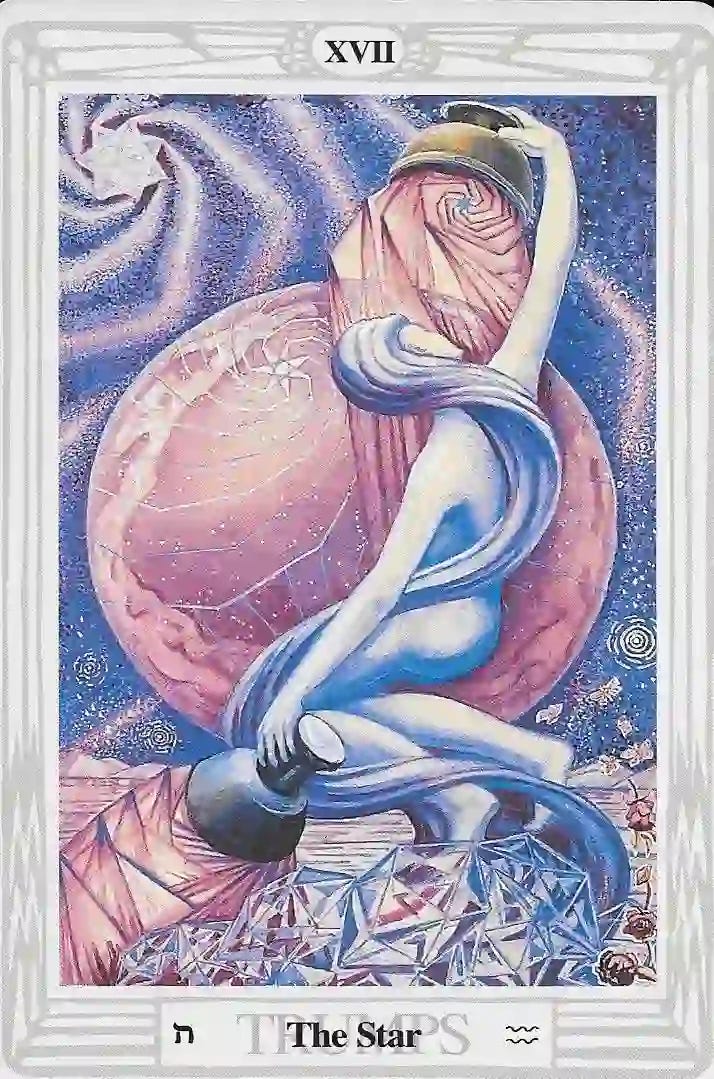

Shortly after finishing Against the Day, a behemoth of a novel set during the years between the Chicago World Fair and the beginning of World War One, this particular disciple, as Mr. Kirsch refers to us in apparently derogatory fashion, found himself compelled to consult a chapter of Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism with a particular suspicion that the key to a deeper understanding of the text lay in the seventeenth arcanum. Lo and behold, the correspondences between the Meditations entry on The Star and the themes running throughout Against the Day proved almost alarming.

Doubling

The first line of the Meditations chapter on The Star concerns two alternative paths: that of Construction and that of Growth, as in: “A tower is built; a tree grows. The two processes have this in common: that they present a gradual increase in volume with a pronounced tendency upwards” (464). While a tree pushes upward and outward through a process of cellular division and growth from within, a tower is built brick by brick. A tree flows; a tower is constructed piecemeal. A tower is dry, a combination of hewn stone and fired brick; a tree is guided by “the universal sap of life” (464).

Plot wise, the novel has many concerns, and, like a splitting stream, it follows all of them. Some reconverge at the other end of a blockage, others are buffered by seemingly interdimensional borders, and they range in tone and context to an astonishing degree, from balloon boys going on comic book style missions across the globe, to highfalutin mathematics, the politics behind a looming world war, and, perhaps the heart of the novel, bloody clashes between labor and capital, manifesting most fully in the story of the Traverse family in which the patriarch, one Webb Traverse, a union miner and anarchist bomber, is murked by a couple agents of the mine’s owner, Scarsdale Vibe. A considerable portion of the thousand-plus pages concerns Webb’s three sons pursuing revenge, albeit somewhat half-assedly. There are also detectives, thruples, peyote trips, and no shortage of holy grail quests. This is, after all, a Pynchon novel.

The splitting, mirroring, and doubling is present in both the novel’s plot and its very structure. In fact, two of the novel’s five sections are given titles in reference to some form of doubling.

The second section of the book is titled Iceland Spar after an incredibly common but vastly useful calcite, totally colorless and famous for its double refractory properties, or its ability to split light into separate beams, so that looking through a piece will show a double of everything within the frame.

The third section is titled Bilocation, or the ability to be in two places at once. For further examples of doubling, see Asia, as in the existence of two Asias, “one an object of political struggle…the other a timeless faith by whose terms all such earthly struggle is illusion” (249), or there is the “small population of optically sawed-in-half subjects walking around New York” (571), or the Intergroscope Merle Rideout and Roswell Bounce are operating by the end of the novel in which a single still image can be shot through with light and its projection followed forward or backward through time, like a film, though “there’s always the chance that those little folks in the pictures will choose different paths than the originals” (1049).

There are also at least two worlds between which characters are able to move, though not exactly at-will. Let us arrange our own pairing here and name them Earth and The World. Earth is the living planet, that alchemical flow of all the planet’s children, sentient and otherwise, into and out of one another, hugged by gravity, tempered by death, renewed in birth and evolution, each form a transmutation. The connections and flows of energy too vast to understand, but a divine mystery to be basked in.

The World, then, is the human drive towards domination and control. It operates according to a single prime directive, profit extraction. It looks into the interconnected flows and sees a realm of units to be frozen, dissected, imprisoned in constituent parts so as to be better labeled and assigned value. It is a task pursued by powerful people in science, religion, and capital, an allegiance Pynchon succinctly refers to as They.

The Star-Woman

There are even two characters named Estrella, which, of course, is the Spanish word for star. Estrella Briggs, who everyone calls Stray, is first encountered by middle brother Frank Traverse in Nochecita, Colorado. She is “real pregnant. Not only showing it, but also that other composed and dreamy thing” (201), having arrived in that condition with the help of Frank’s older brother, Reef, who is nowhere to be found at the time. Pregnancy, fertility, and motherhood are common associations of The Star.

The second Estrella, also first encountered by Frank, is a young Tarahumare girl (though Estrella is just her shabóshi, or Spanish, name) who is traveling with her brother in law, Espinero, who considers Frank responsible for saving their lives, and in exchange leads him to a cave where he finds a flawless piece of Iceland spar that seems to glow, “as if there were a soul harbored within” (391). Espinero instructs Frank to look into it, but warns him to be careful. When he does, Frank receives a vision and learns the location of Sloat Fresno, one of his father’s killers, and uses this information to track him down and exact his revenge.

Beyond the inclusion of these two names, much is made of The Star arcana itself after it appears as the final card (“always the one that matters” (253)) in Dahlia “Dally” Rideout’s reading:

In ordinary divination practice, The Star, number XVII, which at first glance signified hope, was just as apt to portend loss. It showed a presentable young woman, unclad, down on one knee, pouring out water from two vases, her nakedness meant to suggest that even when deprived of everything, one may still hope. A.E. Waite, following Éliphaz Lévi, believed that in its more occult meaning the card had to do with the immortality of the soul.

In his commentary on the Tarot, Alejandro Jodorowsky describes the Star-Woman as “a being entirely connected to [Earth]. One of her vases seems as if it is welded to her body…and the other extends to the countryside.” He notes that the two vessels contain different types of water: spiritual water (yellow) and instinctive or sexual water (blue). He also notes that one of the vessels might be receptive (224).

It should be stated that the cards cited by the characters within the novel are those of the Rider-Waite-Smith deck, as is befitting the turn-of-the-century setting, and both Jodorowsky and the anonymous author of Meditations write with reference to the older Marseille deck. In the instance of The Star, however, the similarities are greater than the differences. In each, a naked woman is depicted kneeling by a body of water beneath a sky of eight stars with a major star in the top center.

The most significant difference might be said to be that the tree with the bird has flipped from being over her left shoulder to being over her right, as if one image is the mirror of the other. . .What the Star-Woman herself sees as she gazes into her reflection upon the water, which, why not?, could be a sort of portal connecting the Marseille world and the Rider-Waite-Smith world between which one might move, as characters frequently seem to do within the novel…

And the bird? Could be that it is just a bird. Or it could represent the added dimension of flight and all that pertains, connecting the heavens to the earth, as above so below, freedom of movement, etc. Could be a spy of Zeus’ ready for some liver, making the Star-Woman Pandora, and the water streaming out of her vessels all manner of curses, as Duncan Barford explores in his Hierophany podcast episode on The Star.

Pynchon references the Aztec story of the eagle and the serpent a number of times. He also uses skies full of eagles to represent desolation. That’s the thing about birds; they’re hard to pin down.

While the range of options for cartomancers during the time in which the novel takes place may have been more limited, rampant commodification of everything, including divinatory practice, in the century that follows, would mean that by the time of the novel’s writing, there were countless additional decks out there for the author to consult. Still, few decks have gone on to join the hallowed ranks of RWS and Marseille. One that has is the Thoth deck developed by Aliester Crowley and Lady Frieda Harris.

Crowley’s one-time hermetic order, Golden Dawn, gets a passing reference in the novel, and, spookily, Crowley’s writing on The Star name drops the mathematician Riemann, whose work is a major theme in the novel. Crowley recognizes Riemann as one of the Prophets of the New Revelation, who revealed that “the straight line had no true correspondence with reality.”

The Thoth interpretation differs aesthetically from Marseille and RWS, but retains many similar elements. There remains a naked woman kneeling while holding two vessels. Here, however, the Star-Woman is said to be Nuith, a goddess in Thelema, and she pours one vessel over her own head and the second upon the junction of land and water. That which emerges from the two vessels differs vastly. The water issuing from the higher cup spirals out. Indeed, Crowley quotes Zoroaster in saying that “God is He, having the head of a hawk; having a spiral force” (110), and we see this spiral force bursting forth, as if it were the very material of the universe. Spirals emit from the star in the top left corner of the card, and are visible upon the celestial body behind the woman whose long braided hair itself seems to spiral up and around her body.

Spirals are circles opened and stretched, so that traveling along its groove returns one to the same location on the x-axis, but the y-axis has transformed. An eternal return of eternal renewing, cyclical time. Contrast that with the water poured forth from the lower cup which appears rather angular, rigid, and without verticality: time’s arrow.

“It is only in the lower cup that the forms of energy issuing forth show rectilinear characteristics”, Crowley writes. “In this may be discovered the doctrine which asserts that the blindness of humanity to all the beauty and wonder of the Universe is due to this illusion of straightness” (111). That the universe is composed of spirals, and humanity, or at least a powerful contingency of humanity, sees in straight lines is a theme picked up both by Pynchon and the anonymous author of Meditations who Juxtaposes the Star with the arcana that comes before it, the Tower, that Construction vs. Growth dichotomy we touched upon earlier.

While The Tower is commonly considered a dread card, Construction, too, is multi-faceted with many different aspects, not all pertaining to hubris and doom. There is not only the Construction towards control, there is the equally human impulse of Construction towards shelter. It is not Construction in itself to be wary of, but Construction that imitates Growth. Not Construction working alongside Growth, which might look something like gardening, as the Weird Studies boys point out in episode 122 of their wonderful podcast, but Construction wearing Growth’s face.

In Tarot commentator Rachel Pollack’s chapter on The Star, she notes that the stars in the RWS deck are eight-pointed, or octograms, which “can be formed by placing one square over another with the points alternating” (124). Here we have the straight line imitating the spiral, a feat technologically beyond humanity’s reach until the time of the novel.

Hope and Desire

The author of Meditations writes that “the lightforce which emanates from The Star is hope…Hope not as a subjective optimism but as objective life-force which directs creative evolution towards the world’s future” (472).

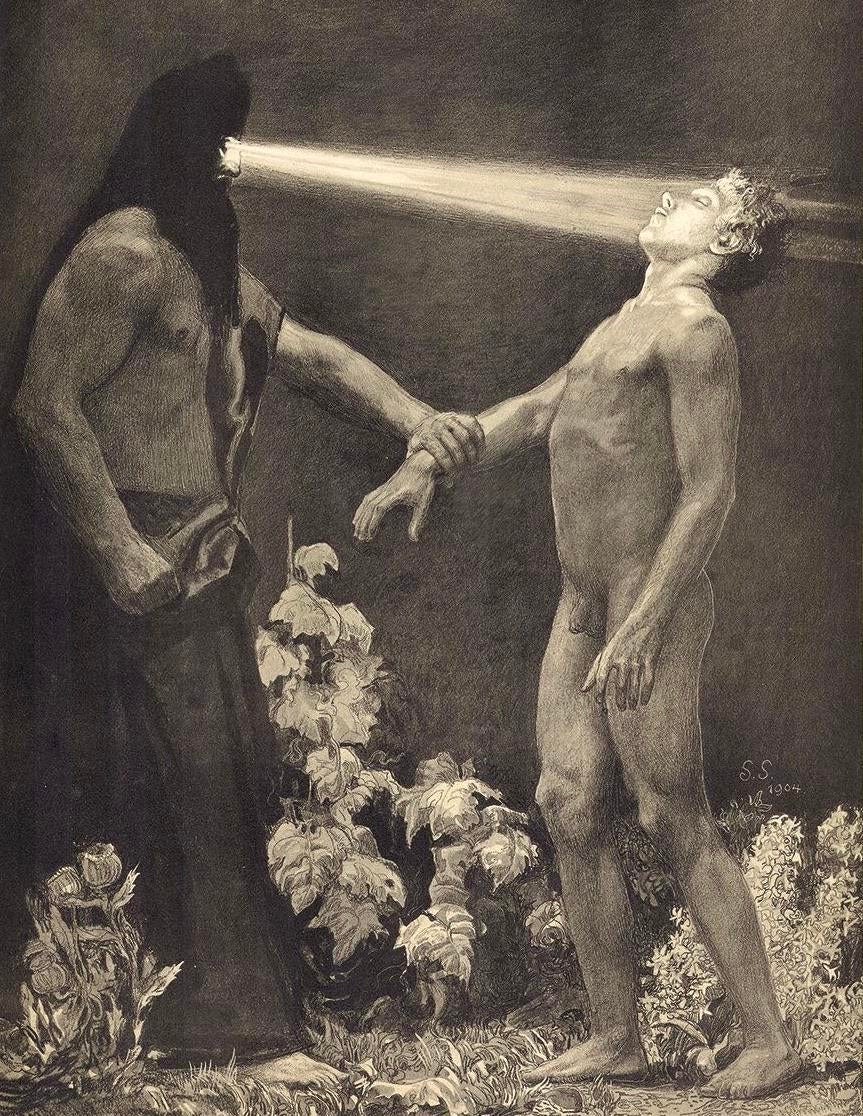

This is a radical statement about light, but not one that would be out of place in Against the Day in which much is made of light, from the Lightarians who live on nothing but (60), to the Native Americans of Chiapas who consider light to be a living tissue, akin to the Christian perception of Christ’s flesh (992). In Pynchon, that light might “[reveal] its deeper secrets to those who approach it in the right way” (59) does not seem so beyond the pale. And here, the anonymous author of Meditations suggests that this light is emerging from The Star with just such a purpose, a quiet guidance. However, for all those who would approach it from the right way, there are also Prometheuses ready to steal the holy fire, such as Roswell Bounce, an intriguing side character, a photographer-inventor with ties to mine-owning oligarch, Scarsdale Vibe.

“I want to reach inside light and find its heart, touch its soul, take some in my hands whatever it turns out to be, and bring it back” (456). This utterance gives voice to the forces working against The Star’s hope, the impulse towards domination over nature, made increasingly possible by the ever-advancing technology of the modern era.

Zeus punished Prometheus for his crime by binding him in chains and sending an eagle to eat his liver. Each night it would grow back and each day the eagle would return until he was eventually freed by Hercules. Zeus also sent Pandora to Prometheus’ older brother, Epimetheus. Pandora had in her possession what often gets mistranslated as a box, but originally was a jar, similar to that which is held by the Star-Woman. This jar contained every kind of evil and misery. When the jar was opened, these things fled their container and entered the mortal world as a sort of counterweight to the stolen gift of fire. And that was exactly what happened, except the lid of the jar was replaced when just one entity remained within, Hope.

Roswell’s stolen fire is his invention, the Intergroscope, that contraption which can project the proceedings and preceedings of a human life based on a single still image and play them on screen like a film. Roswell blatantly confirms his association with Prometheus in a conversation with Merle in which he confesses, “My savior turned out to be more of a classical demigod…Hercules” (455).

That hope remains in the vessel, or that it was contained there at all, alongside all the evils of the world, has puzzled us mortals for millenia. Is hope some dangled prize we shall never attain, or is it the bottomless wellspring directing the rhythms of the world?

In the author of Meditations' view, a tree’s unfolding, what we earlier referred to as the way of Growth, might be said to emerge from the same interior as that radical vision of hope, for acting in each is “the universal sap of life”, that magical agent which links consciousness and action, or the agent of transformation from the ideal to the real.

Alejandro Jodorowsky writes something similar: “The Star is the spiritual guide we carry within who is connected to the most profound forces of the universe and to the sacred” (230). This is hope as the quiet, guiding impetus that strings seemingly disparate beings together into the inseparable flows of Earth. Like a star, it can be followed, but never reached. It is both propulsion and guide, not destination. This hope is the aquifer drawn on by the forces of good in Against the Day, from the miners’ union, to the Mexican revolutionaries, and the balloon boys throughout the novel, each fighting for a somewhat vague, but better future, with a faith that it will unfold through their actions because their actions are in-line with the Earth, even if extremely powerful forces are acting against them.

But what does it mean for hope to remain trapped within the jar, for it to remain forever out of reach, as remote as the stars? Hope itself might remain permanently out of reach, but hope’s earthly manifestation might be said to be desire. Desire is what makes an individual who they are, but desire can also be coded by outside forces and bought off rather cheaply as our heroes on their noble quest for revenge learn again and again. Kit, the youngest Traverse brother, accepts Scarsedale Vibe’s money in order to pursue a life of the mind and study mathematics. Frank, the middle brother, winds up for a time taking a high-paying job amongst the higher-ups of a coffee plantation, and Reef, the eldest, finds himself distracted and waylaid by bourgeois decadence.

Still, The Star’s guidance, for all its vagueness, continues to break through, sometimes as subtly as a guilty conscience and other times in spectacular fashion, such as the Tunguska Event, an atmospheric explosion of an asteroid which flattened eighty million trees in central Russia, described in the text as a “heavenwide blast of light” (779). The event pauses the progress of the novel, moving across the cast of characters to give a range of reactions to the massive explosion which turned night into day, and instilled in witnesses some grand sense of change, but as the event unfolded no further, “As nights went on and nothing happened and the phenomenon slowly faded to the accustomed deeper violets again, most had difficulty remembering the earlier rise of heart, the sense of overture and possibility, and went back once again to seeking only orgasm, hallucination, stupor, sleep, to fetch them through the night and prepare them against the day” (805)

Hope comes from beyond. Desire is what is felt bodily. Sometimes that desire leads to glimpses of true human freedom and potential, fulfilling the same function as hope. Just as often, it seems to disrupt the gentle guidance of the higher impulses of The Star. These seeming opposites are somehow braided together in another act of doubling, for, as the Meditations author tells us, “there is Water and water; ie the celestial Water of the Sap of Life, progress and evolution, and the lower water of instinctivity, the ‘collective unconscious’...the water of floods and drowning” (469).

The Star-Woman pours from two vases which blend into the same stream. “Here is the tragedy of human life and mankind’s history and cosmic evolution. The flow of continuity…bears not only all that which is healthy, noble, holy and divine…but also all that which was infectious, vile, blasphemous and diabolical” (469). That is, a stream is composed of both, and while it can take split and follow multiple directions at once, it cannot unmix itself. It is this lowercase water, desire, that is most vulnerable to manipulation. Even borne from a radical hope, desire can be redirected, subjugated, and controlled when it is not given a strong direction by ideology or bolstered protection by collectivity such as what unites the striking unionists and revolutionaries.

Having neither, the Traverse children are often presented as vulnerable and directionless, ready to fall in with whatever cause they bumble into, a dangerous gambit in Pynchon’s They-haunted world. They, Pynchon’s favorite antagonists, are a shadowy conglomerate of capital’s structure and the humans occupying seats of power. They are rarely seen and their machinations can only be felt raggedly along the edges. Sometimes, though, he will throw readers a bone with action movie-esque sequences of supervillain-spelling-out-his-devious-plan. In Against the Day, we are treated to just such a scene when Scarsedale Vibe addresses a room full of that most euphemistically named of classes, developers:

So of course we use them…send them up onto the high iron and down into mines and sewers and killing floors, we set them beneath inhuman loads, we harvest from them their muscle and eyesight and health, leaving them in our kindness a few miserable years of broken gleanings…

We will buy it all up…all this country. Money speaks, the land listens, where the Anarchist skulked…we fishers of Americans will cast our nets of perfect ten-acre mesh, leveled and varmint-proofed, ready to build on…who will care that once men fought as if an eight-hour day, a few coins more at the end of the week, were everything, were worth the merciless wind beneath the shabby roof, the tears freezing on a woman’s face…whose future, those who survived, was always to toil for us, to fetch and feed and nurse, to ride the far fences of our properties, to stand watch between us and those who would intrude or question...Anarchism will pass, its race will degenerate into silence, but money will beget money, grow like the bluebells in the meadow, spread and brighten and gather force and bring low all before it. It is simple. It is inevitable. It has begun. (1000-10001).

Here we have it: Construction’s desire to conquer heaven, to replicate Growth so that money will bloom like the bluebells of the meadow. The World replicating and replacing Earth. This, more even than the first world war, is the dark foreboding felt by the characters throughout the text. The ability of Construction to imitate Growth is a new development just beginning to come online during the time of this novel, and, when it does, “The world you take to be ‘the’ world will die, and descend into Hell, and all history after that will belong properly to the history of Hell” (554).

Orpheus Out of Hell

In trying to acquire an understanding for his new role as observer of the Icosadyad, Detective Lew Basnight talks to the Grand Cohen of his order. The Grand Cohen is not altogether helpful. Instead, his responses leave Lew genuinely puzzled as to his task, especially when he is told “Suppose there was no such thing, after all, as Original Sin. Suppose the Serpent in the Garden of Eden was never symbolic, but a real being in a real history of intrusion from somewhere else. Say from ‘behind the sky.’ Say we were perfect. We were law-abiding and clean. Then one day they arrived” (223).

Let us, indeed, suppose this exact scenario. This is not the only time the serpent is referenced in Against the Day, not even the first time it is mentioned in connection with a creation story. Frank Traverse beholds a mural depicting a perverted version of the Aztec foundation story of the eagle and the serpent. “Here the snake is coiled around the eagle and just about to dispatch it” (395), and again in Mexico City when revolutionary leaders Madsero and Pino Suarez are killed, Huerta’s rise to power is compared to “allow[ing] the serpent to prevail” (994).

The anonymous author of Meditations is also concerned with the serpent, particularly the serpent biting its own tail, which he conjures as the closed circle which stands in opposition to The Star’s spiral. This impulse creates a prison “Because this circle is closed--not in the sense of the circle’s dimension, since it can grow indefinitely, but rather in the sense that it is and always will be a circle without opening” (480).

In the Cohen’s scenario, the serpent is a force of control, arriving in order to squeeze around nature and force out her secrets, an impulse alive in humanity since the time of Prometheus, and present in the novel in the form of Scarsdale Vibe who, as the owner of a mining company, is literally slicing up the Earth into the smallest pieces possible so as to apply function and value.

Hell is The World set to the side of our Earth. Earth and its irreducible mix of flows moving in spiraling dimensions cannot be replicated. To catch something, freeze it, kill it, slice it up into infinitesimally small parts, and study them, apply value to them, then reconstruct a facsimile reconstructed out of these parts, so that nothing is outside of our knowledge, nothing outside of our control, and nothing without its precise and assigned value, is to create a false world, a dead world, an algorithmic projection, quite literally hell.

This is the piecemeal world Lew looks into when he brings a photograph of his ex-wife to Roswell and Merle to be played through their Intergroscope, a world of single frames and conjectures, a place totally disconnected. What Lew sees leaves him confused and longing. It is similar to what Espinero tells Frank when out hunting for rabbits, “You have fallen into the habit of seeing dead things better than live ones…You need practice in seeing” (392). That is because Frank is from the epicenter of Hell, has grown up under its influence, for the place most explicitly aligned with Hell is America, as made clear in one of the book’s many Orphic references: “Please--don’t look back..or he’ll take you below…Down to America” (962).

The burgeoning America would only stand to grow in power with the onset of World War One. “Central governments were never designed for peace. Their structure is line and staff…The national idea depends on war…and a general…war…would be just the ticket to wipe Anarchism off the political map” (938).

Here, anarchy is functioning as more than a political philosophy, and the central government is more than a nation state. It is the structure of the line against the spiral. Anarchy is that which refuses to be sorted, that which is beyond control, such as the striking miners’ camp near the end of the novel where Frank and Estrella and Estrella’s son, Jesse, join the miners even as the Colorado National Guard is brought in and eventually opens fire in a fictionalization of a true event in which twenty people in the camp were killed, including miners’ wives and children, in what is known today as the Ludlow Massacre, orchestrated in part by John D. Rockefeller, Jr, one of the most acutely bloody acts of capital vs. labor in the long, sad history of the United States.

Out of this massacre, Estrella, The Star escapes, along with her son. Frank stays behind to partake in the fight, and from his vantage watches as Estrella, The Star, becomes Orpheus (“He wasn’t even sure what it cost them to not look back” (1017)).

The Star-Woman as Orpheus, with her persisting hope of leading the damned out of hell, forever pursued by the Furies that would slice her up into parts, but who can never silence her song.

Works Cited

Anonymous. Meditations on the Tarot: A Journey into Christian Hermeticism. Angelico Press, 2020.

Barford, Duncan. (2023, July 15). Ideality. Hierophany. Acast. https://shows.acast.com/hieropha/episodes/hierophany-17-ideality

Crowley, Aleister, and Frieda Harris. The Book of Thoth. 1972.

Ford, Phil and Martel, J.F.. (2022, May 11). Spirals and Crooked Lines: On the Star Card in the Tarot. Weird Studies. https://www.weirdstudies.com/122

Jodorowsky, Alejandro. The Way of Tarot: The Spiritual Teacher in the Cards. Destiny Books, 2009.

“Ludlow Massacre.” Wikipedia, Wikimedia Foundation, 14 Apr. 2024, en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ludlow_Massacre.

Pollack, Rachel. Seventy-Eight Degrees of Wisdom: A Tarot Journey to Self-Awareness. Weiser Books, 2020.

Pynchon, Thomas. Against the Day. Penguin, 2006.

Love that Chagall.

Welcome to Substack, by the way!