With the second entry in this series on distop-yin literature, we move out of Joy Williams’ purgatorial malaise, and into somewhat more familiar territory—

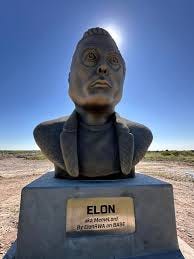

“Fernando A. Flores didn’t mean to write a novel about Elon Musk’s Texas,” or so goes the headline of Texas Monthly’s interview with the author. And while Brother Brontë is certainly more than that, it is also that. The novel takes place in the near-future, down in Three Rivers, an abandoned husk of a Tech City about equidistance between San Antonio and Corpus Christi. In reality, Three Rivers is home to about 1500 people, and a major Valero refinery. In the novel, however, it has gone through a major boom-and-bust cycle. Having been selected as the site of a new Tech City, the small town is quickly built up into a metropolis, in a move reminiscent of Starbase, Elon Musk’s new company town.

Three Rivers as an artificial city has already failed before the events of Flores’ novel. We are not given many details about its downfall beyond a grim one-liner about cheaper labor having become available elsewhere, assumedly due to the general collapse that has occurred. Whatever happened, the population has dwindled. For those who remain in the emptied-out city, opportunity has been whittled down to survival, however one can. This sense of carrying on after the end of something haunts the novel: “It was springtime in Live Oak County and the remaining acres of rainforest were far away, being chopped up like a cold lobster on its back” (34).

Failed State

Our guides through this world are varied, but former punk rocker, Neftalí, is foremost. The novel starts out (following the brilliantly evocative opening line “Rain fell hard like slabs of ham”) with the aftermath of a police raid on Neftalí’s family home. The house has been ransacked, the collection of books and music destroyed or confiscated.

After the raid, Neftalí sets out with her 'mana and former bandmate, Proserpina, who are in turn joined by former bassist turned crypto lackey, Alexei, and a younger woman named Moira with whom they travel to the Big Tex Fish Cannery which sits on the edge of town, “stinking like a gangrened seaport thanks to its three onyx smokestacks, which perpetually released the grizzly rot of processed verdillo fish” (42).

The cannery is owned by Three River’s Mayor, Pablo Henry Crick, and operates more as a labor camp for women than what one might think of as a legitimate business.

“It was against state law for any mother of a child to be unemployed, so with the scarcity of jobs, most grown women in Three Rivers ended up permanently barracked at Big Tex, which required its workers to also live there” (42-43).

The Cannery is operated in a more traditional 1984 yang-style dystopia. The women are held prisoner, given little to no freedom, and perform grueling labor for the enrichment of the cannery’s owner, receiving little more than room-and-board for themselves and ration cards for their dependents.

Outside the cannery walls, however, it is something much closer to LeGuin’s concept of a yin dystopia, a world in which the social cohesion has utterly collapsed. Indeed, the powers of oppression, no matter how effective, have their seat only in the local mayor rather than some all-powerful Big Brother, and just one town over the citizens have managed to carve out a scrappy little socialist community for themselves.

While we can stretch the concepts to make them fit, Flores does not consider himself a dystopian writer. As he tells Texas Monthly, he sees himself as a realist, and reality is much more mixed than utopia/dystopia.

Flores’ characters certainly display much more agency than those in Harrow, but the novel itself is not driven by any particularly strong plot line. For the most part, things happen and characters respond. They do what they can to make a life in such a place with many of the driving events (including (SPOILER!) the eventual worker-mother rebellion that destroys the cannery) occuring off-screen, so to speak.

“I’ve been okay,” Neftalí tells her dead mother’s former partner, Bettina, who she visits at Big Tex. “Just thinking about the future. While trying to be very aware of the present moment” (54).

During this visit, Neftalí gifts Bettina a copy of one of her favorite books, Ghosts in the Zapotec Sphericals by Jazzmin Monelle Rivas, the author of novel-within-the-novel, Brother Brontë. It is the best she can do after the destruction of the book she’d been asked to bring, Understanding Urban and Agricultural Hydraulics, at the hands of some neighborhood boys working, once again, at the behest of the Mayor. Reading, you see, is illegal in Three Rivers, except for inside the cannery. Hence the initial raid on Neftalí’s home, and the destruction of her library and music collection.

The meat-and-potato value of art objects in their physical form is a major motif in the novel. They shine out as sources of hope, knowledge, and even power, and for that reason are banned, yet they continue to pop up, physical manifestations of the yin powers that weave together the largely female opposition to Mayor Crick, for in Three Rivers yin is not only a symbol of collapse, but a mode of resistance, the ties that bind a society together.

Liminality

Cell phones and computers have largely disappeared. Connection to the outside world is limited to newscube, a state-provided device in which pre-recorded news reports are played on a loop. Books are illegal and roving bands of neighborhood boys are deputized to confiscate reading material and feed it to nasty little wood-chipping robots. That is— while they’re not busy scheming about popularizing Teddys, a localized, privatized currency reminiscent of crypto, albeit a physical version alchemized out of bottle caps rather than something ethereal on the blockchain.

If that sounds a little similar to our current book-banning, crypto-endorsing regime, here’s another strange coincidence: There are a lot of plane crashes and mass deportations within as well. In one darkly comedic vision, a train derails (possibly due to the massive energy-drain of a machine used to create Teddys?) and leaps towards a low-flying plane:

“Flight 809, deporting prisoners from an overcrowded immigration camp in Tulsa, was the ninth plane in the span of two weeks to inexplicably nosedive into Three Rivers…moments before the crash, the railroad steel on the ground below had inexplicably bent towards the plane’s nose, then snapped, just as an Amtrak bullet train heading to Tucumcari was speeding by. The train shot up and crashed head-on into flight 809, the pilot and conductor locking eyes in those final moments” (201).

That erased separation of air travel and railroad, heaven and earth, is just one of the hard line borders that becomes blurry in Brother Brontë. The town itself is named for its proximity to three rivers (the Atascosa, the Frio, and the Nueces) which become a single river just south of the town’s borders. Rivers are liminal in a way that their blue outlines on a map do little to convey. Dogen writes that rivers are realized in water. Water must carve its own channel. This is the slow power of Yin: dark, wet, easy, receptive, containing, but never set. Rivers dry up—especially in Texas. They flood. They divert into new channels. Their borders are fictions, as are all borders, and in Brother Brontë this is put on display again and again.

Roughly halfway through the book, night and day become confused as a “crude, shapeless smoke and ash [block] the sun and moon and stars” (184). This half-night obscures the remainder of the novel, and is caused, most likely, by a volcano in Mexico (yet another example of natural phenomena completely ignoring legal borders. The volcano may have erupted in Mexico, yet its effects become global)—but there are other theories:

“What do you think about the rumors that the sun is no longer actually up there? That the government exploded the sun, and that’s what the clouds actually are, just pieces of dead sun floating over us? Do you believe that the moon got really, really jealous? Jealous, like out of that passionate kind of love, and the moon killed the sun for looking at the Earth a certain way? Because that’s what I think happened. It’s weird, because really, it’s the moon who has her eye always here and always there. Only showing you some of her face, depending on how she feels. Always keeping us guessing” (193).

Then there is prison and work. Any boundary between has broken down as all mothers in Three Rivers are forced into labor at Mayor Crick’s fish cannery until the time that their children become property owners.

Likewise, dream and reality become porous, with dream images manifesting in reality, as well as the novel within the novel from which the latter takes its name. A snippet of the nonfiction biography of the fictional author, Jazzmin Monelle Rivas, makes up the center section of Brother Brontë, so that it is a blinkering of fiction and reality, fiction and reality, all the way down.

Identity is also blurred as Self and Other can swap, as displayed in just one such case of mistaken identity in which identical twins Moira and Phoebe carry out an assassination plot that may or may not have killed the mayor, for, you see, not only are truth and misinformation blurred, but even life and death. Phoebe reports there is no way the mayor could have survived her attack, but the newscube reports otherwise. Elsewhere characters are able to communicate from beyond the grave, and one even returns from apparent death.

As David A. Ulin writes in his review in The Atlantic,

“For all the many ways that the border is commonly represented—as a political and geographic demarcation, a projection of fear and xenophobia—it is also, most essentially, a provocation to readers to widen their lens. Borders, by their nature, are elusive, a set of shifting lines on a map that tell us nothing about who lives on either side. In that sense, what else can this border be if not a laboratory for fusion: individual, collective, national, international? Brother Brontë is a novel that seeks to refashion it all.”

The novel might even be said to take place in a sort of temporal border, a Pynchonian window in which the status quo has been blasted and the future balances, for a moment, upon a precipice, able to tilt one way or another. The characters are largely scavenging a life for themselves out of the wreckage of a failed state. Texas continues to exist on some level, and the ruling class seems to carry on much as before, albeit behind more guarded walls, but the bulk of society is now fending for itself however they can.

Borders have always been the seat of such encounters, places where Empire asserts itself most robustly and violently, as in Roberto Bolaño’s 2666, a novel set in Santa Teresa, a town inspired by Ciudad Juárez, the manufacturing hub along the border of Mexico and the United States, a place treated by the US basically as a colonial outpost, a source of cheap labor and supply, where violence is allowed to reign as long as production continues uninterrupted. A huge section of 2666 consists of reports of crimes against women which take place in Santa Teresa. Flores seems to allude to it when Proserpina returns from apparent death, and Neftalí recounts an old story

“‘where a fisherman finds a suitcase in the river. And inside the suitcase is a mutilated woman. When the…police…announce the hunt for the killer, all these men appear at the station to confess to the crime. They’re all sobbing their eyes out, shivering, ridden with guilt, so it’s difficult to believe they’re collectively making up their pain. However, it’s also hard…to believe that this many men killed only one woman. I mean, what kind of superwoman was she? In the end, it turns out that so many crimes against women went unreported that these men were all clearly guilty of killing a woman in the exact way the mutilated woman was found. When they heard of the suitcase, and the hunt for the killer, they assumed it was their own particular crime and couldn’t stand living with that terror, so they confessed.’

‘And who went to jail?’

‘I forgot. Nobody, probably’” (236).

But borders are more than a place in which violence is applied to the vulnerable. They are also the place in which resistance to such violence stands most vigorously, as we have seen from the remarkable fortitude of the Palestinian people, and in the novel in the form of mutual aid groups which arise to help one another survive.

Tamales

At the end of part one, Proserpina stumbles upon a lucky find, of sorts. She discovers a suicide letter that bequeaths the property of the man who wrote the letter to whoever finds it.

“Present this note to the magistrate and cleric’s office. Have them transfer all of it over to your name. Life has given me enough, and I have taken enough” (102).

Colonel Huerta owned not only a large home, but a barn in which an injured tiger is discovered. Proserpina quickly sends for Neftalí before falling into a ravine and disappearing from the narrative for a hundred-twenty pages. Neftalí and friends search for Proserpina, and eventually discover a body they take to be hers, so Neftalí, believing her friend to be dead and buried, delivers the letter to the cleric’s office and becomes the rightful owner of Colonel Huerta’s estate in her stead.

Consequently, Bettina is released from the fish cannery, for Neftalí, who had been listed as a dependent, has become a property owner.

Bettina takes a job at the food bank and finds accommodations outside of the cannery. She puts off going to see Neftalí and gets into making paper. One day a knock comes at her door, and, after another case of mistaken identity, Bettina accepts the young knocker, Gia’s, invitation, and goes with her to help a group known as the tías distribute tamales among the people who are living in the wreckage of the derailed train and crashed plane.

The tías occupy “the topmost floor of the Live Oak tenement building, and with their joint effort they made around a hundred dozen tamales two or three days a week, which kept the poorest people in Three Rivers fed” (198).

The plane/train wreck, like a level in Fallout, has become a little village out past the outskirts of town. “Boxcars crookedly lined up like trailers fallen from the sky” (203). In the makeshift village, there is a young woman in labor. It turns out to be Proserpina, who is feverish and speaking in Arabic, which no one can understand. Bettina reveals she has some experience in midwifery and attends to the birth while the “destitute community crowded [around]—silent witnesses to a child brought into this ash-covered world” (209).

The young woman who had informed the tías about the woman in labor says she has not seen a pregnant person for a long time, not since she was a girl, and this is true for the other people in the camp as well. It is hard not to think of Alfonso Cuaron's film Children of Men, set in a world in which two decades of human infertility have brought society to the brink of collapse.

The late Mark Fisher writes brilliantly on the film in his Capitalist Realism:

“The catastrophe in Children of Men is neither waiting down the road, nor has it already happened. Rather, it is being lived through. There is no punctual moment of disaster; the world doesn't end with a bang, it winks out, unravels, gradually falls apart. What caused the catastrophe to occur, who knows; its cause lies long in the past, so absolutely detached from the present as to seem like the caprice of a malign being: a negative miracle, a malediction which no penitence can ameliorate. Such a blight can only be eased by an intervention that can no more be anticipated than was the onset of the curse in the first place” (6-7).

The resistance in Brother Brontë is not occurring on a grand scale. It is everyday mutual aid, it is help at the most immediate level, best exemplified in the scene of the tias’ tamale distribution. Such acts can blossom, as we are shown, into the neighboring community of George West, where people do not live easily, but they live communally. Food and labor are shared, and a life of some integrity can be lived. This is no easy achievement, though, and it must be fought for in the conditions one finds themselves. This is one thing in the sparsely populated, agricultural world of George West, and quite another in the urban decay of Three Rivers.

The tamale operation is brought down in a senseless act of retribution. Following the worker-mother uprising, a police and vigilante crack down occurs, targeting not only the run away worker-mothers, but any who might be sympathetic to their cause. This leads to a bomb being planted in the top floor of the Live Oak tenement building to destroy the tías’ home, and wipe out their capacity for distributing food to the hungry.

Fire, the elemental sign of Yang, is used again to destroy a home, this time Neftalí’s new accommodations where she is harboring not only the returned Proserpina, an illegal act in itself, for, as a new mother, Proserpina is subject to work in the cannery, but she is housing the tías and their family following the destruction of their own home, and she is still harboring the injured bengal tiger, who she has named Mama, that was found in her newly acquired barn. The neighbors had previously demanded Neftalí get rid of Mama, but she refused, so eventually they arrive literally holding pitchforks, and throw flaming boots through the windows of the house, catching the curtains on fire.

Gia, the tías’ teenaged niece, and Mama are the only two inside the house at the time of the fire, although the tías quickly arrive on the scene and set to work fighting the gathered posse and slowing the flames’ growth from the outside. Meanwhile, Mama retreats up the stairs, and Gia follows.

Sometimes a piece of artwork has at its core a single flaming image, as Jack Smith called it, a potent picture out of which everything else unfolds. In Brother Brontë, that image takes form in this scene of the burning home. The volcanic ash has choked the sky for some hundred pages. Shadows are extinct. Everything is covered in ash, and all seems hopeless. The sky is murky brown, all this surely exasperated by the smoke from the burning house there upon the darkened plains of South Texas, and the mob is closing in.

Goddamn, I wish I could paint because I can see it so clearly—

The desperate, ragged crowd, gathers about the burning house. Some are fighting to keep it ablaze, others to put it out, when suddenly, after months of darkness, a “blanket of clean daylight [unrolls] from the junkyard sky…Some [shield] their eyes, having grown unused to the spectacle of the sun” (321), and everything stands still as the girl and the tiger are pushed out onto the second story awning. The clean sunlight of God’s own eyes seems to shine down just as the house is ready to collapse in flames. In that moment, Gia has no choice but to grasp onto the tiger’s fur, to deny all overcoding and trust the very definition of the Other, a wild, panicked animal, not only that, but a Tiger, the apex of all predators. She must reach out and grasp Mama’s fur and together they fly down to safety.

[Exit Music]