“If everyone found Jesus, that would do the job, but what does Jesus mean?” Matt Christman asks in his appearance on the Talk Gnosis podcast.

Now I’m a lifelong resident of Texas and am painfully familiar with the threat of theocracy, but that’s not what Mr. Christman is getting at here. I am thinking now of the meme of the child asking if they can have something only for their mother to tell them they already have that thing at home, the punch line lying in the reveal of the off-brandedness of the thing at home.

Well the Jesus we’ve got in Texas is a hateful bigot being pushed on the rest of us by a handful of West Texas oil men funneling their billions to politicians who are willing to carry out their vision of Christian nationalism, and they have been highly successful in driving Texas further and further right. Some of their victories include the increasingly militarized border (along with a newly revitalized hate for those who may have crossed it), the forcing through of the highly unpopular school voucher system which will take taxpayer money away from public schools in order to prop up private, religious schools. At the same time, public schools are getting a splash of 'at holy water with a push to reintroduce prayer time, biblical curriculum, ban books, and erect ten commandments monuments in every classroom. Beyond this indoctrination of school children, they are also leading effective campaigns against same-sex marriage, abortion, and trans rights (or even recognition).

Meanwhile, the Jesus the hypothetical meme child is asking for is more like the promise of human redemption through universal brotherhood. The kingdom of heaven come to earth. Or an escape from the Black Iron Prison, to both quote Christman and reference our old friend Philip K. Dick.

As Above, so Below

“The class which has the means of material production at its disposal, has control at the same time over the means of mental production, so that thereby, generally speaking, the ideas of those who lack the means of mental production are subject to it.”

–Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The German Ideology

The current capitalistic stranglehold has become a hegemonic lifeworld. It exists by denying the reality of any alternatives. It sets the limits of existence. It gets into the hearts, souls, and minds of its subjects and recreates itself there. There is a wildly popular saying that gets variously attributed. I first came across it when I got into Mark Fisher. You probably already know what I’m gonna say—

Together: It is easier to imagine the end of the world than the end of capitalism.

This becomes less true when one is able to see beyond the limits of this lifeworld, and fundamentally untrue when one can conceive of something to replace it with. Finding Jesus, in Christman’s terms, could mean simply this: not only rejecting the given premise thereby escaping from its chokehold, but formulating an opposing lifeworld with which to replace it, one like the Christian ideal of Universal Brotherhood. But even this heroic act is of value only if it occurs in solidarity. Everyone must do it together in order to throw off the yoke of the capitalists’ regime.

Without such a vision, the end of our totalizing system by other means would result in not only societal collapse, but it would also mean a sort of personal collapse, as the correlating structures within are demolished as well. This would not occur instantaneously, as when an invading alien force is stopped by the destruction of the mother ship, but slowly and painfully. One would be reshaped to correspond to the new (even more) fallen world. This is what we see in the alienscape of post-apocalyptic visions such as the Mad Max universe and Fallout, people becoming demons in order to survive hell.

“Chaos

is God’s most dangerous face—

Amorphous, roiling, hungry.

Shape Chaos—

Shape God.

Act.Alter the speed

Or the direction of Change.

Vary the scope of Change.

Recombine the seeds of Change.

Transmute the impact of Change.

Seize Change.

Use it.

Adapt and grow.”

The mind of the average American subject is curdled from living outside of reality. The most sophisticated and expensive propaganda machine in the history of this planet is working night and day to project a different version of reality, one of American exceptionalism and PeRsOnAl FrEeDoM and that this is the greatest country known to man, blessed by Gawd Almighty and all that. Meanwhile, lived experience speaks a different story to an increasing portion of the population, one of daily struggle, alienation, and deep loneliness.

As those two worlds, the projected and the lived, slip further apart, the individual is put under enormous stress. Those at the levers of the means of mental production turn up the fear, hatred, and scapegoating in order to pave over that growing gap.

There have been similar such crises in the past and they have forced realignments. The New Deal comes to mind. Not a fulfillment of capitalism’s pie-in-the-sky promises, but a narrowing of that schism between projected and lived, at least for a large enough portion of the population to relieve the psychic pressure on the system. However, these have been temporary measures. The modern American Middle Class was a compromise between capital and a powerful labor movement that no longer exists, made against the backdrop of post-war abundance, a stable environment, and the Cold War. It did not rise spontaneously out of the free market, nor was it given by the ruling class out of the kindness of their hearts, but neither was it the full package demanded by a radical and powerful labor.

Put more cynically, one could say they were bought off.

And now the deal is up and we’re not getting it back. The material gains and comforts have been slowly walked back over the last forty-plus years, so that the middle class is a dying breed, and all those conditions under which it was created have crumbled. Labor has no position. Post-war production has been offshored, and no amount of tariffs will bring it back, except maybe in automated factories without a fraction of those mid-century jobs. China has replaced the Soviets as a Cold War competitor, but propaganda there has been largely effective so that the average American believes every Chinese citizen is living the life of a medieval peasant, and so the ruling class has no incentive to increase quality of life with a deluge of treats and low interest rates in order to compete.

Most importantly, the environment is not so stable. There is no longer even much of an illusion that we’re in this for the long haul. It’s crunch time, baby. We’re riding this rickety nation into the sunset and if you fall off you fall off. You have no power but that of a consumer. Complain to a manager if you can flag one down and see what that does for yah.

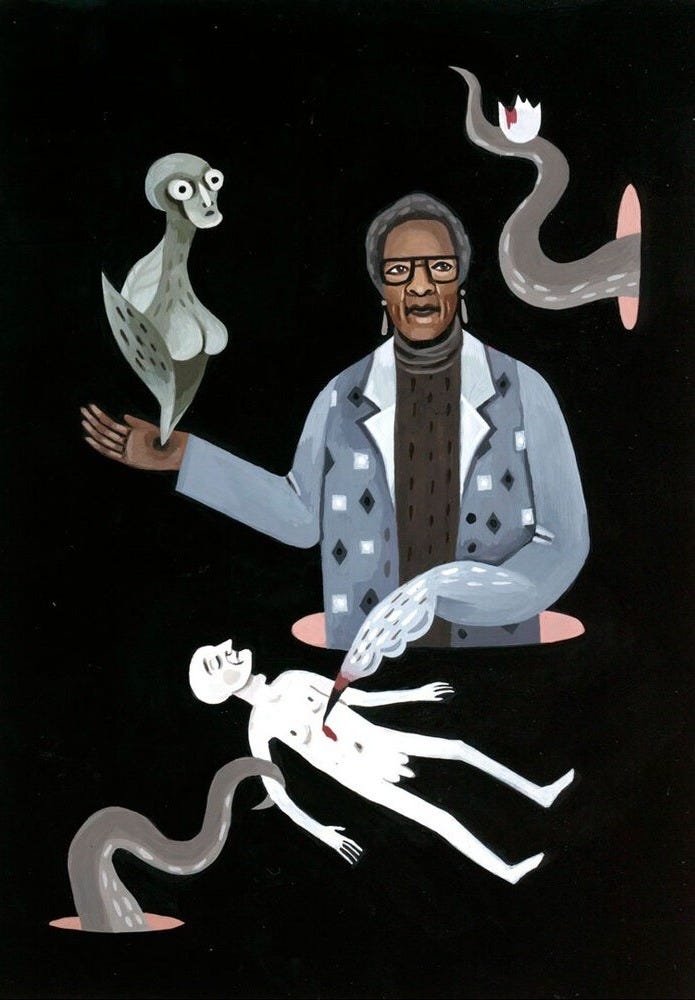

The gambit taken by Octavia E. Butler in her Earthseed series (Parable of the Sower (1993) and Parable of the Talents (1998)) is that people united by a shared vision could not only survive a collapse of the system, but even thrive on the other end by radically changing the social relation between the individual and the collective. The interior structures would still come down, but this would be a freeing action, as Jonathan Scott explores in Octavia Butler and the Base of American Socialism:

“What becomes clear toward the end of the tale is that the intention of Lauren’s ‘God is Change’ maxim is to crystallize, into a single slogan, the dialectical unity of opposites under post-capitalist society, to which she has given the name ‘Earthseed’: the individual (‘Change’) and the collective (‘God’)”

But we’re getting a little ahead of ourselves here.

In case you’re late to the party, Octavia Butler’s two novels are enjoying something of a second life right now, spurred on by some of their eerily prophetic synchronicities with the current moment, in which they are set. The first book kicks off in 2024, in a walled neighborhood in Southern California. Our hero, fifteen year old, Lauren Olamina, lives here with her family: her preacher father, step-mother, and younger brothers. They are far from rich, but they are better off than the vast majority of people living just beyond the wall who survive by squatting in abandoned buildings, stealing their food and supplies, selling one another into slavery and forced prostitution, murder, and even cannibalism.

Deteriorating climate conditions have resulted in the general collapse of the liberal order. In the first of the two novels, agents of the state are rarely seen beyond the local police who operate for bribes, and are just as likely to rob you as those they are meant to be protecting against. There is no emergency response, no sense of a larger order. We are yet again in one of Le Guin’s yin dystopias. People have been left to fend for themselves and much of the nation has descended into chaos. There are rumors that things are better to the north, where water is more abundant, especially the Pacific Northwest, Canada (who has closed its border), and Alaska (which has seceded, apparently successfully, which is one of the biggest hints towards the hollowed-out weakness of these United States), but we are stuck way down in southern California with no way to verify such rumors, and nothing to do about it even if they did prove true.

As the books move through the decade at a rather brisk pace, corporations begin to fill the power vacuum. Company towns offer stable work, if only in exchange for room and board. Many operate in a way that resembles indentured servitude, if not outright slavery. There are stories of employees who are never able to work off their debts and becomes indebted to the company for good. Corporations are then able to sell and trade their workers, breaking apart families, and destroying lives. Still, some people are willing to take the deal in exchange for the stability and protection these corporations are able to offer.

But there are others who refuse to believe this is the best they can hope for. From a child, Lauren Olamina understands the precarity of their situation. She has grown up sheltered from the worst of conditions, and that is lucky for her, for she has what is called hyperempathy, meaning she feels what those around her feel. This mutation, brought on by maternal drug use during pregnancy, is a physical embodiment of the core of Lauren’s future movement, for it breaks down the divide between herself and others. In a world that mostly feels pain, this mutation should act as a huge handicap. Instead, it spurs Lauren on towards what she conceives as her destiny, for when you physically feel your neighbor’s pain you want to relieve it as badly as you want to relieve your own. It is the true meaning of collectivism. Everything shared, pleasure and pain alike.

In part because of her condition, Lauren is well aware of their situation despite her young age. She can feel in her body that their little walled neighborhood is an island in a hostile sea. The first section of the book consists of Lauren constructing “her theory of post-capitalist social relations” (Scott) and trying to envision a way forward, but as with every socialist movement it can only be planned so far. Like Mike Tyson said, everyone has a plan until they get hit in the face. Lauren’s ideas, if they are to come to fruition, must eventually shape themselves on the ground, in action, ever-adapting to the moment:

“I’m trying to learn whatever I can that might help me survive out there. I think we should all study books like these [on wilderness survival, firearms, native plants and their uses, log cabin-building, livestock raising, plant cultivation, and soap making, etc.]. I think we should bury money and other necessities in the ground where thieves won’t find them…I think we should fix places outside where we can meet in case we get separated. Hell, I think a lot of things. And I know—I know!—that no matter how many things I think of, they won’t be enough” (58 Sower).

Lauren confides this and more in one of her fellow teenagers living within the fortified village who becomes understandably frightened by the prospect. Her friend tattles and Lauren ends up getting a talking to from her father who she also urges to prepare the community. While he does begin to lead shooting lessons and to post a night watch, he, too, is unable to see the full reality of their situation. It’s not that he is simply content to hold onto as normal a life as he can while he waits for the old ways to return, but he was shaped by those old ways and is frozen in this new world. Ultimately, he cannot change as fully as he must to meet the situation, and eventually he disappears on his way to work outside of the walls, and is never heard from again.

Such a stance should be familiar to us. It is easy enough to see that things are dire and something must be done, but it is quite a different animal to transform oneself into the type of person the crisis calls for. It is so much easier to recoil, to seek comfort in the known, and try to recreate a familiar past. This series has gotten a lot of press likening Trump to the second book’s President Jarrett, but Sower’s presidential hopeful, Christopher Charles Morpeth Donner, has a lot of Biden parallels. In a time of great crisis, he is a personification of those who are just waiting for normalcy to return.

Lauren, having no attachment to that past, sees right through it:

“he’s like…a symbol of the past for us to hold on to as we are pushed into the future. He’s nothing. No substance. But having him there, the latest in a two-and-a-half-century-long line of American Presidents makes people feel the country, the culture that they grew up with is still there—that we’ll get through the bad times and back to normal” (Sower 56).

Anti-Trad

Lauren turns out to be something of a prophet. Not only did she foretell the community’s eventual demise, but she has been harboring another idea, one she won’t even confide in her friends or father. These are the writings and ideas that will prove to eventually germinate into a new religion, something she calls Earthseed.

“I didn’t make it up. It’s the truth,” Lauren explains again and again when she does begin to share her vision. “All the truths of Earthseed existed somewhere before I found them and put them together. They were in the patterns of history, in science, philosophy, religion, or literature” (Talents 125). And although she does admit, at one point, “People forget ideas. They’re more likely to remember God—especially when they’re scared or desperate” (Talents 198), that does not mean Earthseed is a cynical religion, or a Trojan Horse system invented to sneak in other ideas. Lauren is a true believer and Earthseed a true religion.

Indeed, with its roots in lived reality rather than metaphysical speculation, or divine revelation, Earthseed has more in common with the earliest religions, those which grow directly out of a way of being in the world. These are the earliest forms religion took, and are rather unrecognizable compared to the world religions of today, abstracted and compounded upon by millennia of theology.

Historian of religion (and total monster) Mircea Eliade wrote that the sacred was the point of maximum reality. For Lauren, and the followers of Earthseed, that point is change, and in change they find the idea of a mystical unity between all things:

“We have lived before.

We will live again.

We will be silk,

Stone,

Mind,

Star.

We will be scattered,

Gathered,

Molded,

Probed.

We will live

And we will serve life.

We will shape God

And God will shape us

Again,

Always again,

Forevermore.”

While Butler reports she based much of the writings of Earthseed on texts such as Tao Te Ching (a text I’ve made a habit of collecting in various translations, and of which a friend once said: “If the New Testament is Jesus from the outside, the Tao Te Ching is from within, that’s the way God’s brain works.”), but it wasn’t just ancient Chinese texts I was reminded of in reading snippets from The Book of the Living, the name Lauren gives her collection of religious writings. Butler’s nascent fictional movement at times reminded me of something quite different, not a seed but a pill, a grillpill.

Matt Christman became something of a folk hero, largely for young, leftist men of the overly online, and often, emotionally stunted variety, when he began hosting his Cush Vlog, in the early days of the pandemic and the sad aftermath of Bernie’s second campaign when many of us accolades were feeling quite lost. As Alexander Zaitchik writes in his history of the vlog:

“By the time Christman moved to Los Angeles in late 2021, the show had outgrown its founding metaphor. Though still operative, the repurposed ‘Matrix’ meme of the grill pill turned out to be the seed for something bigger. The tendrilled monologues were not collections of distinct rants, bits and observations. Connected by mycelium-like threads, they formed a whole organism — a singular style of inquiry that fused existentialism, humanistic socialism, and cultural theory, wrapped and ribboned with the mystical sensibilities of psychedelia.”

Like Lauren saying she did not make any of it up, but pulled from a wide range of existing sources, Christman moves easily through history, politics, online culture, and spirituality in order to weave a coherent structure of what Zaitchik calls the Vlog’s true subject, alienation, and not only the structure, but movements towards an antidote. The idea behind the grill pill isn’t to tune the political world out and focus on the hedonistic pleasures at hand. It is to scale down. To focus on what you can actually affect. To not burn yourself out by being obsessively online but, instead, try to connect with those around you in a deep way.

“That is what Christianity brought to the world stage: the idea that we could bring about a collective reunion with Christ, with the universe, with God. This is the important part about being alive. We could make the Kingdom of Heaven on Earth as we imagine when we imagine what heaven is like. We could live it as our lives on Earth and then when we die there would literally be nothing to fear because we would not have had a life of regrets and selfishness and violence and denial. We would have a life of communion and connection and fellow feeling…our engine of libido would be hooked to a social mechanism that would reinforce our desires and and resonate them across a community rather than have this fundamental contradiction between our best interest as an individual and the best interests of people around us.”

Butler writes “Belief initiates and guides action —Or it does nothing.” Christman often offers a similar provocation to his listeners: “if you are looking for a reason to stay behind the computer…that means that you don't actually care about politics. You care about being on the computer and talking about politics is one of the things that makes it fun… look yourself in the mirror and ask ‘Do I really care about any of this political stuff?’”

It is easy to kneejerk against such a question. I run a prestigious blog where I use literature to write about politics, so of course I’m doing politics, I want to say, but isn’t that just being on the computer? Am I not frozen in fear by the overwhelming crises out the window? Lauren, meanwhile, is forced to put her money where her mouth is quite early on in the first book when her walled neighborhood is overrun and burned to the ground. Her family and most of her community members are killed, and she is left homeless and alone on the outside.

Over the course of the first book’s final two-thirds, Lauren makes her way up the long stretch of California, heading north, that vague direction representing hope. She teams up with the only other two survivors she finds from her town. It is slow going as they recover from the injuries and trauma sustained in their escape, not to mention the dangers of the road. They walk along the blasted interstate in a sea of people moving in the same direction. Vehicles are rare and travel mostly at night. The roaming hoard is highly individualized. Each person looking out for themselves or their small group, and showing only paranoia and distrust to all others. Rape, thievery, arson, and murder are common as flies.

Lauren disguises herself as a man on the road as the trio travels cautiously, but they do not let the same paranoia infect them. They offer help where they can and in this way their group begins to grow. Despite her age, Lauren, enlivened by her belief, becomes the de facto leader, and as her confidence grows she begins to share her ideas about Earthseed with the others. She is surprised to find many people are quite open to it, and this shared belief bolsters their collectivity and deepens their trust and purpose.

By the end of the first book, they reach a plot of land in northern California rightfully owned by Bankole, a middle-aged doctor who’d been traveling there to join his sister. Upon arrival, they find she and her family have been killed and the house burned, but the land remains, and it is out of the way of the hoards on the interstate. Bankole offers it as a home for the group, by then consisting of thirteen people. The first book ends with a decision to halt their progress north, and to try to make a go at it here, at the first Earthseed community, a place they name Acorn.

God is Change

So what is this Earthseed God all about, anyway?

The central tenant is simple: God is change.

This does not mean God is a powerful entity evoking change from some transcendent locality, as many characters misunderstand Lauren as saying: a natural assumption for those from a society that popularly perceives God as a daddy-in-the-sky type entity. She means just that: God is change. Change is the defining quality of the universe. This is not a God to be worshipped, but one to be reckoned with if only because we live as a part of their reality, and deluding ourselves into falsities hinders only ourselves.

“We do not worship God.

We perceive and attend God.

We learn from God. With forethought and work,

We shape God.

In the end, we yield to God.

We adapt and endure,

For we are Earthseed,

And God is Change” (Talents 15)

By the start of book two, five years have passed since the founding of Acorn, and the community has grown to include sixty-four people. They have established a society complete with religious and social practices. Possessions are held in common. Housing is guaranteed. Work is evenly distributed, as is food and education. Each member of Earthseed is taught how to read and write, and are expected to learn at least two languages—usually English and Spanish—but the structure is not top-down. The social relations have been realigned so that anyone who knows a trade is always in the process of teaching it to someone else. Likewise, after a sermon, the floor is opened up to questions and discussions. No one can just dictate their point of view from a position of power. They must be able to defend it and convince others. In this way, the movement is already becoming, in Deleuzianspeak, rhizomatic.

The community grows their own food, as well as gathers wild herbs, fruits, vegetables, and nuts. They have fortified their borders, and made themselves competent in self-defense with a range of weaponry. At the same time, they have established friendly relations with neighboring communities with whom they have begun to trade. It is a hard life of toil, but it provides safety and community to its members, something previously unknown to almost all of them, but for Lauren this is not enough. Earthseed is not meant to be a communal farm in the hills of northern California, but the promised redemption of all mankind, so the slow growth frustrates her to no end:

“The Destiny of Earthseed

Is to take root among the stars.

It is to live and to thrive

On new earths.

It is to become new beings

And to consider new questions.

It is to leap into the heavens

Again and again.

It is to explore the vastness

Of heaven.

It is to explore the vastness

Of ourselves.”

While I have a twenty-first century skepticism of space colonization, a belief that Mars is for Quitters, and that we’d be much better off focusing that time and energy on healing our own planet, I can admit that much of this cynicism is derived from one man, Elon Musk. In 1998, Musk was a virtual unknown, just a shit-kicker fresh off his daddy’s blood diamond mine, busy funding the development of the internet yellow pages. So I can be open to this idea from the nineties that Earthseed’s destiny is to reach Mars.

While Butler’s America may not have Musk to contend with, they have their fair share of villains. President Donner has been replaced by the leader of a fundamentalist group known as Christian America, Andrew Steele Jarret, who rises to power (under the slogan “Make America Great Again”, no less) by winning the 2032 presidential election, and pressing a brutal theocratic rule on the broken nation.

“Jarret supporters have been known, now and then, to form mobs and burn people at the stake for being witches. Witches! In 2032! A witch, in their view, tends to be a Moslem, a Jew, a Hindu, a Buddhist, or, in some parts of the country, a Mormon, a Jehova’s Witness, or even a Catholic. A witch may also be an atheist, a ‘cultist’, or a well-to-do eccentric” (Talents 15).

Lauren understands how the situation looks. She knows Earthseed is seen by some as the cult in the hills, “those crazy fools who pray to some kind of god of change”, but she hopes their size and remoteness will keep them from drawing any unwanted trouble with Jarret or his crusaders, but that is not to be. Christian America has made any deviation from the norm illegal, so this ‘pagan cult’ cannot be allowed to stand.

While Lauren and Jarret both signal the way forward as a renewed covenant with God, they are not at all in alignment. Earthseed is not a call for a return to tradition, but instead for a new orientation towards God, or a new understanding of the oldest God. What Butler and Christman share is a promotion of living in and adapting to the world as it is. Christian America, meanwhile, projects its own ego upon a divine power and then enforces its already existing prejudices under God’s name; sound familiar?

Earthseed lives in this world, and convenes with reality itself, which enables them to survive. This is illustrated in some very simple ways from the beginning, such as Lauren’s family’s favorite treat being acorn bread, a recipe for which they found in a book about the Native Americans of California.

In the America of the recent past, food had become totally detached from reality. Practically any fruit could be had in any locale at any time. This is not a humanity that is living in sync with their environment. This is a humanity that is living at a total remove from the world around them. Acorns are a plentiful and native food source, but they are often overlooked. My own backyard fills with them every fall, and I just think: squirrel food.

It is this very neglect of the natural, native world that proves to be the demise of Jarret’s forces after they invade Acorn.

Acorn is occupied by heavily armed forces who strap shock collars around the necks of all her inhabitants. These collars are capable of delivering immense pain on command, or if its wearers go out of the invisible boundary, or if they attempt to remove it, or attack its controller. These are collars meant to control, to choke out any change. The citizens of Acorn are turned into labor camp prisoners in their own homes and they have their children, including by this time, Lauren’s own young daughter, taken from them. And there is no hope of rescue because the population at large believes these reeducation camps to harbor only the worst, most violent criminals.

Here, again, there are so many connections to the current moment in which untold numbers of immigrants are being painted as violent prisoners, having their families broken apart, and shipped off to foreign concentration camps without even the formality of due process that these books would have been considered painfully on the nose had they not been written some thirty years prior, but Butler is not a prophet. She simply could see America for what it is. These problems are not new. They spring from long simmering resentments that have never been addressed adequately. She simply draws out what so many others are content to ignore.

Lauren’s dreams of continuing to grow Acorn and spreading Earthseed’s message out from there is destroyed. The community is held in captivity for a year and a half, living as prisoners, forced into labor, tortured, and rendered defenseless by their collars. Lauren holds onto hope, knowing God is Change, and that eventually their circumstances must, therefore, change. And one day they do:

“Day before yesterday, we had a terrible storm…and a landslide. The hill where our cemetery once was with all its new and old trees, that hill has slumped down into our valley. Our teachers had made us cut down the older trees for firewood and lumber and God. I never found out how they came to believe we prayed to trees, but they went on believing it. We begged them to let the hill alone, told them it was our cemetery, and they lashed us. Because they forced us to do this, the hillside has broken away and come rumbling down on us” (251).

Christian America’s neglect for the environment, their inability to live in the world rather than projecting their reality onto the world, proves their downfall. Tearing down the trees destroyed the root system that held the hill in place, so that the next big storm brought it all down. The mudslide takes out the collars’ command unit, and the members of Acorn stage a brutal recapturing of their home.

After their victory, because of the righteous violence wrought against the guards, they cannot stay. They are still viewed as convicts and after what they have done will be more sought after than ever. Each member must scatter to the wind to avoid retaliation. Acorn will not be the central core for Earthseed, as Lauren had hoped. Such a place cannot exist in a country ruled by an antagonistic, theocratic regime. Earthseed will have to spread in other ways.

The early rhizomatic structure of Earthseed becomes essential to its spread. Rather than a central core, Lauren begins scattering seeds. She sets up a massive mutual aid network where each person is able to contribute based on their own particular situation and talent. Money, shelter, and labor (including care work) can be distributed through this network that slowly spreads its reach until Earthseed becomes a powerful entity that is able to protect its communities, send its youth to university, and work towards their destiny.

Lauren spends her life tirelessly growing Earthseed, and the closing pages detail the first shuttle heading for Mars in the year 2090. By then she is too old to go herself, but has arranged for her ashes to be sent on the first ship after her death.

Earthseed is adulthood.

It’s trying our wings,

Leaving our mother,

Becoming men and women.We’ve been children,

Fighting for the full breast,

The protective embrace,

The soft lap.

Children do this.

But Earthseed is adulthood.Adulthood is both sweet and sad.

It terrifies.

It empowers.

We are men and women now.

We are Earthseed.

And the Destiny of Earthseed

Is to take root among the stars.

[Exit Music]

<slow clap> the thing to remember about the New Testament is that it's empire-approved stories about stories about a man that taught marginalized people how to build alternative communities. The Roman Empire was at it's peak and all the nationalism that goes with that while Israel was rife with nationalist sentiment whether it be power-hungry religious leaders or revolutionaries ('what have the Romans ever done for us?!'). Rome wasn't good for Jesus' people and neither was his own nation so he showed them how to non-violently be something different and non-threatening. The power of resurrection isn't some hocus-pocus otherworldly thing: it's that you can't abuse people who don't care if you kill them. Jesus' followers went off away from society and created the kind of communities they needed to thrive in an intentionally non-threatening way. But it made Rome look bad and attracted a lot of people and eventually Rome had to stop martyring early Christians because it was attracting too many converts and sympathy. Then in 380 Christianity became the state religion of Rome and Christian Nationalism was born because if you can't beat them, join them. Except there's no such thing as Christian Nationalism because Jesus taught an anti-nationalist message. Any time you see a Christian Nationalist you're seeing a literal false prophet.

I’ve always said the communism of Orthodox Marxism is nothing more than the Kingdom of Heaven on earth. Its socialist eschatology