Touch Grass (and the Grass Touches You Back)

On Annie Dillard's "Pilgrim at Tinker Creek"

Weird Nature

In his recent work on Christian mysticism, Simon Critchley devotes a chapter to Annie Dillard who is totally at home amongst the medieval monks, saints, and anchoresses who occupy the majority of the book. Critchley writes: “What drives Dillard…is the effort to find a holy firmness at the core of things that connects those things to God and to us” (191).

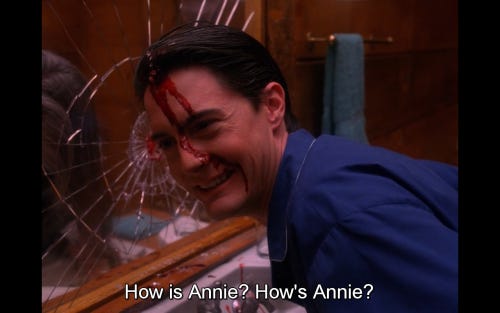

He then quotes Dillard in asking: “If [God] has abandoned us, slashing creation at its base from any roots in the real; and if we in turn abandon everything— these illusions of time and space and lives—in order to love only the real—where are we?”

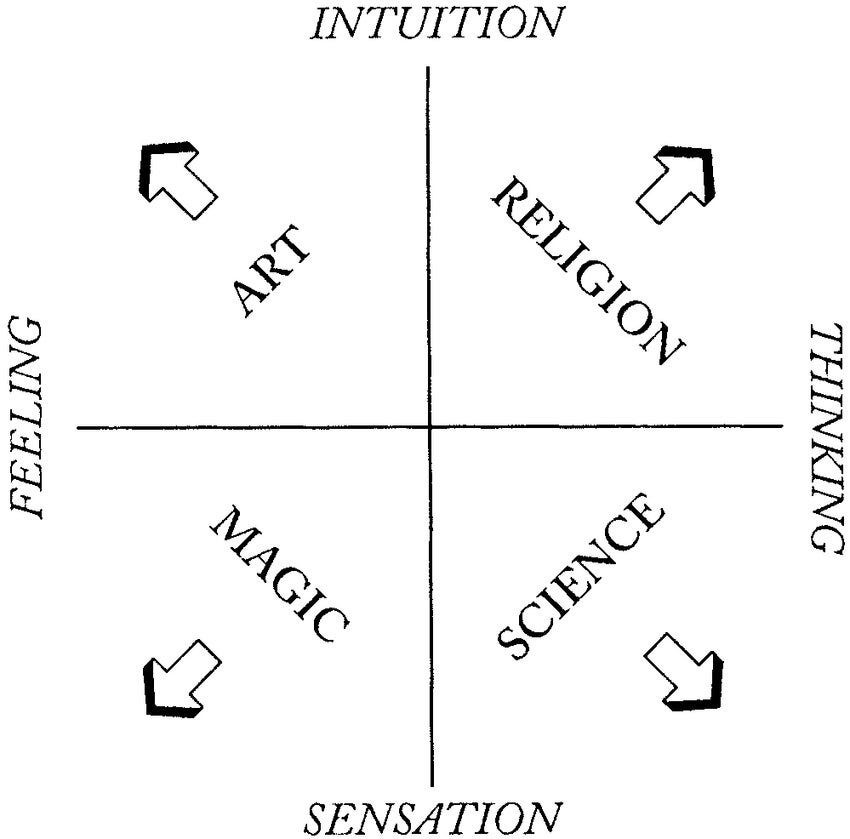

To begin to address such a question, Dillard makes beautiful use of a genre I here deem Weird Nature. If Gnostic Pulp is a strand of literature, then Weird Nature is one of its nonfiction cousins. It is a similarly chimeric form of writing, pulling its sources from the full array of human modes of understanding. While it is not within the purview of the Weird Naturalist to dispose of science as a way of engaging with the world, a book of Weird Nature would be unfit for teaching a biology class because this strain of nature writing removes science from its esteemed pedestal, not to dump in the garbage bin, but to place back among the rest of the riff-raff of human modes of understanding: art, religion, magic, metaphor, and, perhaps most importantly, wonder. Ultimately, what defines Weird Nature is its focus on the experiential.

Perhaps no novel evokes the properties of Weird Nature better than Moby-Dick, which peddles in science, religion, art, and magic for over two hundred thousand words, and somehow, by the end, The Whale is made more mysterious than ever. That is the danger of engaging with the world in such a way. Everything becomes intensified and teems with an intelligence fit to its nature: a worldview akin to, if not outright, panpsychism, then at least something close enough to smell panpsychism’s farts. William James called it radical empiricism, if that sits easier with you.

But would-be panpsychists beware: Melville offers a warning about entering into such an engagement with the world: “The only mode in which you can derive even a tolerable idea of [the whale’s] living contour, is by going whaling yourself; but by so doing, you run no small risk of being eternally stove and sunk by him” (307).

Indeed, such engagement is not only dangerous, it can be immensely difficult. It requires practice, maybe even the capital-P kind of Practice.

“I am sitting under a sycamore by Tinker Creek. I am really here, alive on the intricate earth under trees. But under me, directly under the weight of my body on the grass, are other creatures, just as real, for whom also this moment, this tree, is ‘it’. Take just the top inch of soil, the world squirming right under my palms. In the top inch of forest soil, biologists found ‘an average of 1,356 living creatures present in each square foot…Had an estimate also been made of the microscopic population, it might have ranged up to two billion bacteria and many millions of fungi, protozoa, and algae—in a mere teaspoon of soil’” (94).

Couldn’t you just throw up? What a dizzying glimpse into the sublime. Who could go about their daily life with such conscious knowledge? “The effort is really a discipline requiring a lifetime of dedicated struggle” (32).

Dillard cites philosopher Martin Buber throughout her text. In Buber’s philosophy, as laid out in I-and-Thou, there are two primary words: I-Thou and I-It. The I in each of these primary words cannot be thought of as the same I. Compounded with the latter, the former is transmuted. When one opens themselves up to that vast flow of beings, they cease to be one. The dualistic veil is lifted. Dillard refers to the Hassidic tradition of “assist[ing] God in the work of redemption by ‘hallowing’ the things of creation” (94). This is done, she writes, through an act of merging, an act that requires a tremendous heaving of spirit.

Such a tremendous heave is reflected in Buber who goes on to write, “The primary word I-Thou can only be spoken with the whole being” (3).

So what is the whole being?

A Brief Foray into the Arcane Speculations of Ramsey Dukes

"A scientist calls it the Second Law of Thermodynamics. A poet says, ‘The force that through the green fuse drives the flower/Drives my green age’” Dillard (181).

Though it is perhaps unlikely and indeed unnecessary that all or any of the writers working in the field of Weird Nature have been aware of the work of the rather obscure British magician, Ramsey Dukes, the genre’s approach fits rather smoothly into the system Dukes devised in his seminal work, S.S.O.T.B.M.E.

Building off the work of Jung, who found that thought was composed of intuition, observation, logic, and feeling, Dukes says of his system: “Any practical method of thinking demands at least two of these four elements, one to serve as an input of impressions and the other to process them. Artistic thought uses feelings and intuition, Religious thought uses intuition and logic, Scientific thought uses logic and observation, and Magical thought uses observation and feeling” (2). A fuller picture of the world, he implies, requires all four approaches, which, taken together, have the makings of the whole being.

While sharing a similar appearance to a political compass, Dukes is insistent that his chart should not be thought of as such. Different disciplines should not be placed within each sector, for the chart is fractal and infinitely divisible, nor should one be led to believe that a scientist is never guided by intuition, nor an artist by sensation. We are talking of directions, not ingredients. “The question is not so much ‘what faculties does a scientist use?’ but rather ‘however the discovery was made, which way is the scientist facing?’ ie how is the discovery justified or defended?” (4-5).

Example: Jane Goodall was brought in to study chimpanzees as something of an outsider, to put it lightly. As she got settled in the wilds of Gombe, she did something that might seem quite natural, but at the time was considered almost a taboo: she gave the chimps she was observing names. In an interview with The Guardian’s Robin McKie, Goodall defends herself thusly: "These people were trying to make ethology a hard science, so they objected – quite unpleasantly – to me naming my subjects and for suggesting that they had personalities, minds and feelings. I didn't care.”

Observation, in its basest form, consists of an observer and the observed, an impenetrable circle around each. An I observing an It, to put it back in Buber’s terms. The I might consider itself to be dynamic, but the It can only be static, like steer marked for beef. “They are all bred beef: beef heart, beef hide, beef hocks. They’re a human product like rayon” (4). Everything that defines It is there, within the circle, it must only be observed, understood, and recorded.

According to such a worldview, the universe is made up of a finite number of Its. The number might be astonishingly large, but, given enough time, each It could hypothetically be observed, understood, and recorded, not by any one I, but by a long lineage of I’s working towards the same task. While incredibly daunting, given enough time, this is something that could conceivably be done.

This slow, methodical unraveling is far too clean an approach for the Weird Naturalist, for whom there are no impenetrable circles. Everything is in flux. This is the universe as bubbling swamp, and the Weird Naturalist is the one who tromps through the muck, encountering not Its, but Thous, a world of minds, beings on equal footing as themselves, capable of triggering any manner of metamorphoses.

In such a world, the full range of Dukes’ flexible and fractal map is an invaluable tool. Goodall put it to use marvelously. While clearly working within the field of Science, she made use of a basically Magical approach, that is Feeling + Sensation, (or Pattern Recognition), in coming to see the individuality of each chimp. (It should be added here that in Dukes’ schematics, feeling has less to do with emotion and more to do with what we might refer to as ‘the gut’, as in ‘gut feeling’.)

By bestowing names, Goodall entered into an I-Thou relationship. While the It is a static figure, Thou composes another intelligence, one who is dynamic, capable of growing and changing, thus demanding of respectful observation in order to begin to form a relationship. The I-Thou approach opened Goodall’s eyes to possibility and led to one of the most remarkable scientific discoveries of the twentieth century. It was the chimpanzee Goodall named David Greybeard who she first observed creating and using a tool for termite fishing, something considered at the time an impossibility, as tool-use was reserved exclusively for human beings.

So it is in the fractal nature of Dukes’ system, the merging and melding of these directions, in which the world reveals itself to the careful observer, though never fully. “The fundamental difference between [Van Gogh’s] painting…and a botanical diagram of sunflowers…is that whereas the diagram eliminates every anomaly in order to represent the abstract specimen, the painting eliminates all that is general in order to conserve only the anomaly”, J.F. Martel writes in his Art in the Age of Artifice (50). One is not superior to the other, rather they are complementary. Superimposing the two can only concentrate our connection to what are called sunflowers.

For a fuller exploration, and clearer definition of terms, one should really read Dukes’ S.S.O.T.B.M.E.: an essay on magic, but, for the purpose of this investigation, an openness to bringing a plurality of viewpoints to bear on a single subject, without the illusion of ever arriving at something like total understanding, will suffice.

Weirdo in the Creek

Annie Dillard confesses “I am no scientist.” That does not mean she is in any way anti-scientific, for Dillard is clearly comfortable with science and references a huge number of scientific studies throughout her text. Dillard is simply an enigmatic figure, one who cannot be pinned neatly in a single category. In a recentish piece in The Christian Century, in which she interrogates her own position within that religion, she writes that, while she identifies as Christian, she does not give intellectual assent to most, or maybe any, Christian dogma, and throughout Pilgrim she makes easy reference to Christianity, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, and several indigenous religions, maintaining an equal validity to each, and often when she invokes the word god, it seems to be in the sense of the old Nordic word, reignn, which can be translated, according to Lewis Hyde, as organizing powers (106).

“I live comfortably with paradox, that something can be both true and untrue.”

Critchley understands this aspect of Dillard well. “She is a writer who is at once fully idealist and fully materialist. Only when both ways of seeing are present…do we get a sense of what we are and what we do” (192).

This pluralistic slipperiness is exactly what enters her 1974 classic into the canon of Weird Nature. On the surface, Pilgrim is an account of the author’s visits to the creek running through her neighborhood, but it does not take many pages for the reader to realize such a banal explanation does not begin to cover the true action, which is an investigation into the nature of reality, to which she applies a formidable range of modes, resulting in a work that drips with every bit as much Weirdness as something like PKD’s Exegesis.

“Scholarship has long distinguished between two strains of thought which proceed in the West from human knowledge of God. In one, the ascetic’s metaphysics, the world is far from God. Emanating from God…furled away from him like the end of a long banner falling. This notion makes, to my mind, a vertical line of the world, a great chain of burning. The more accessible and universal view…is scarcely different from pantheism, that the world is immanation, that God is in the thing, and eternally present there, if nowhere else. By these lights the world is flattened on a horizontal plane, singular, all here, crammed with heaven, and alone. But I know that it is not alone, nor singular, nor all. The notion of immanence needs a handle, and the two ideas themselves need a link” (194 Critchley).

Critchley makes much of this soldering of immanence and eminence, but Dillard holds it almost lightly. She is able to move between the two even while seeking the point where they join, where eternity clips time, understanding one cannot force the world to reveal itself in this, or any other, particular way. “I cannot cause light; the most I can do is try to put myself in the path of its beam” (33).

Dillard’s gnosis is revealed to her not in a single moment of mind-shattering anamnesis, but slowly, in flashes, and because she has faith in the meaning of things, or, rather, that things have meaning, whether or not they are for her to understand. Through patient and open observation, through the Practice of Merging, one might catch a glimpse of what is easily missed. “The world is fairly studded and strewn with pennies cast broadside from a generous hand” (15). The trick is, then, to cultivate a healthy poverty and simplicity, so that finding a penny will literally make your day.

Such engagement is difficult. There is a tendency to overlook things that we feel have been defined, and of course in so saying I am only implicating myself. When I feel I have hiked a certain trail enough times, I will stop returning to it. When I have identified the species of a certain tree, I will stop noticing it, as if the species name is all there is to know. Oh, that? It’s a live oak—but what is a live oak?

Dillard writes of an island in Tinker Creek which she visits each month of the year, saying she comes to it as to an oracle and that, perhaps, is as good a working definition of Weird Nature as any: nature writing in which nature becomes teacher, not object to be studied. “I see something, some event that would otherwise have been utterly missed and lost; or something sees me, some enormous power brushes me with its clean wing, and I resound like a beaten bell” (11).

This bellstruck feeling might well be familiar to anyone prone to romping through, sitting amongst, or simply observing ~the natural world~. It was certainly familiar to me when I first came across the passage.

Years ago, your humble Substacker was so struck while walking the trails at Spring Lake Natural Area, a preserve resting just above the headwaters of the San Marcos River. The park offers a variety of bluestem meadows and brushy woodlands, dominated by live oaks draped in Spanish moss. In the spring, when the mountain laurels bloom, a fog of grape soda settles heavy upon the air. It was here, at the edge of the Texas Hill Country, where I was struck by that enormous power Dillard speaks of. It was as if a word had been beamed into my mind: Oompfwa, complete with its etymology: the apeish word for beauty. Ever since, it has become a mantra I often mutter to myself while hiking. A reminder that Nature likes to give gifts. The world likes to pal around. A falling leaf might jolt the hiker in the eye, and there will be a sound like distant laughter, but nature is hardly all fun and games, and Dillard does not simply romanticize her time spent in the woods.

Quite early in the text, she recounts a story of walking along the creek bed, scaring frogs. She was enjoying watching them leap into the water. When she came across one who did not move, she knelt to investigate and witnessed not a single brave individual, but rather the drained husk of a frog which then sank into the water and disappeared, a giant water bug having paralyzed it, liquefied its innards, and slurped it dry. Here we have a glimpse of the theodicy, or investigation into the problem of evil in a supposedly good and loving God’s universe, running throughout the text, for unlike a biologist, the Weird Naturalist must contend with the problem of evil. In this, Dillard departs from the optimism of the transcendentalist writers that are her closest ancestor, in order to engage with all aspects of nature.

“I never ask why of a vulture or shark, but I ask why of almost every insect I see. More than one insect—the possibility of fertile reproduction—is an assault on all human value, all hope of a reasonable god” (63). On the topic of insects, John Keel, the leading voice on everyone’s favorite insectoid cryptid, ends his book, The Mothman Prophecies, with a similar question: “If there is a universal mind, must it be sane?” (296). But perhaps it is an overleap to go straight to the insane God hypothesis. Might we rather have a clearer view if we move ourselves from the center, revoke our self-proclaimed title of God’s Favorite Child, and accept we are but one in an endless multitude, that perhaps God has no fixed image by which to be created in; that Nature is profligate, and we no more centered than a giant water bug?

Dillard’s pilgrimage to Tinker Creek is a baffling view into continuous creation, a de-centering zone in which there are no closed circles. Nothing is fixed in easy meaning. Everything is a mystery with a plurality of explanations, yet no final answers. She describes her investigations into this place as exploring the neighborhood, implying that the subjects of her writing are not plants, animals, and geographic formations, but rather her neighbors, her comrades in existence, who she approaches with a background in theology, a wonder akin to magical thinking, an amateur naturalist’s scientific knowledge, and the artistry of literature.

But traveler, beware. Assisting God in the work of redemption is a dangerous task. The I-Thou hyphen ties the Weird Naturalist umbilically to the world. Melville’s warning stands. To enter Weird Nature is to evoke Pan. Touch Grass and the grass touches you back.

Works Cited

Buber, Martin. I And Thou, Touchstone, New York, 1996.

Critchley, Simon. Mysticism, New York Review Books, New York, 2024.

Dillard, Annie. Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, HarperCollins Publishers, New York , 2009.

Dukes, Ramsey. SSOTBME: An Essay on Magic, Turner, Petersham, 1979.

Hyde, Lewis. Trickster Makes the World, FSG, New York, 2010.

Keel, John A. The Mothman Prophecies, TOR, New York, 1991

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick, HarperCollins, New York, NY, 2017.

Martel, J. F. Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice, Evolver Editions, Berkley, CA, 2015, p. 22.

McKie, Robin. “Jane Goodall: 50 Years Working with Chimps | Discover Interview.” The Guardian, Guardian News and Media, 26 June 2010, https://www.theguardian.com/science/2010/jun/27/jane-goodall-chimps-africa-interview.

Since my first reading I have gone back to the _Fecundity_ chapter multiple times a year. I continue to find it incredibly moving and thought provoking.

It's not often I finish a piece like this and am moved to say "hell yeah" at the end. Annie Dillard is awesome, I love the concept that she's straddling all of these traditions and comfortable in all of them. Her writing can be both romantic and utterly dry/measured at the same time like no one else I've read.

Also never looked into Jane Goodall but that's cool she named the monkeys.