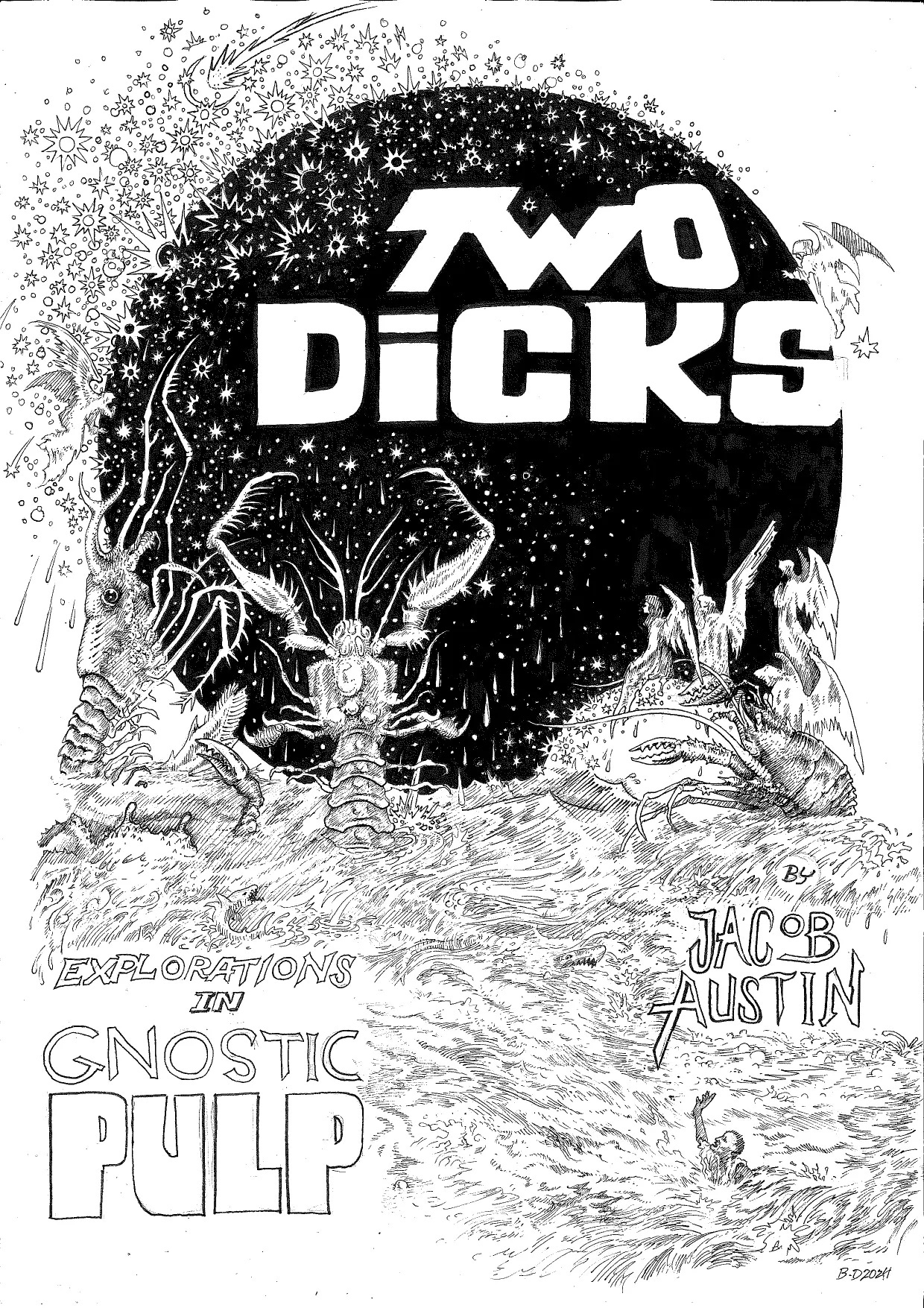

Two Dicks

On Philip K. Dick and Moby-Dick

In noir parlance, dick is slang for detective. If I were to break out my cork board and red string, I would find that there are varying theories for the origin of this slang, but it’s nothing a few days in the office wouldn’t get to the bottom of. Cue montage of quick cuts: alarm clock blaring at an ungodly hour, gurgling coffee pot interrupted by a hand yanking it from its hotplate, cigarettes, phone calls, shoes slapping the pavement, questioning alleyway bums and strip club dancers, consulting texts in ill-lit libraries, back to the rathole office where moonlight pours through paranoid window shades, collapsing into a green leather armchair and pulling open the bottom desk drawer, pouring a nip of bourbon, and sighing while leaning back to look at the board in full.

There would be three main nodules where lines of string meet in proliferation, perhaps emphasized by all-caps notation, and further highlighted by circle or underline. Other nodes would be struck through and accessorized only with a swarm of question marks, leaving us with three leading theories, as laid out by Private Investigator Adam Rostocki:

Theory 1) Dick is a simple shortening of the word detective.

Theory 2) The Romanian word dik, meaning to see or to watch, was adapted by the criminal aspect of Los Angeles and New York to refer to those who watch.

Theory 3) Joyce Emmerson Preston Muddock’s literary detective, Dick Donovan, left such a lasting imprint on the genre as to become a shorthand for the archetype itself.

As is tradition, the grand reveal would not be visible in order to allow for a more cinematic revelation. At some point, this last piece would suddenly tie everything together, and the hypodermic needle would plunge the pie-in-the-sky, tinfoil hat, real psychoshit directly into the living vein of reality. In this case, it arrived in a moment of gnosis. It was revealed to me that the true reason for the derivation of the slang word dick was in order to provide the material that would link the stray stars of this essay into a constellation of meaning. I cannot hope to explain the atemporal, synchronous function by which this occurred, but there can be no other explanation.

The dicks we are here concerned with are not detectives. They are not out drawing politico-dark capital connections behind seemingly garden variety murders. Rather, they are concerned with the nature of reality itself. Though these dicks do not move directly through the noir lens, they inhabit a cousin world, related through the umbrella of pulp. These dicks are key figures of what I would consider the grand American literary experiment, Gnostic Pulp. Gnostic Pulp is more a unifying theory than a distinct genre in itself. It is a mode of literature in which deep investigations into the nature of reality are mashed up against dime novel tropes, genre subversions, general buffoonery and other such pulp lowbrowisms.

The first chapter of German philosopher Peter Sloterdijk’s major investigation, You Must Change Your Life, focuses on the poem from which the book derives its title, Rilke’s Archaic Torso of Apollo. Here, Sloterdijk suggests it is the penultimate line rather than the famous final line that is more enigmatic: “for there is no place that does not see you” (21). Truly internalizing the idea that the headless statue of Apollo is able to return your gaze represents a radical, if ancient, idea: the world is made up of intelligences. Behind the veil of object, everything is subject. Accepting this, Sloterdijk argues, is a skill that can be practiced and further developed, or else ignored and left to wilt, but “where it operates, objects elastically exchange places with subjects” (23). This is the major move of Gnostic Pulp, and the connecting tissue that allows it to span genre. It takes this view seriously. It can be done incredibly subtly, or rather more obviously, but the Gnostic Pulp world is a world of panpsychism, of a sort of neo-animism, a world made up of intelligences rather than matter, whether the characters within the works understand this or not.

In classic noir, we see a version of this in the gumshoe who pays attention to people otherwise treated as invisible, for what better witness to a crime than an invisible person? The gumshoe might have connections among prostitutes and taxi drivers, or be the only one who thinks to ask the maid’s story. This simple act of human recognition is not a gift given; it is not an It being redeemed by the generous actions of an empathetic I, for it is the I who receives the gift, whether it be the detective receiving an important piece of information, or, in the more spiritual sense, Sloterdijk writes that he is able to “receive the reward for [his] willingness to participate in the object-subject reversal in the form of a private illumination” [24].

Every author of Gnostic Pulp is involved in some amount of this religiosity, what we might call spiritual dicking, but the dicks who prove most central to the remainder of this essay represent two distinct aspects by which those working in Gnostic Pulp make their investigations. First, there is, of course, the late master and sci-fi mystic, Philip K. Dick. Second, and I admit this one requires a tad bit of stretching, but look at the territory we are in. Stretching is the only way to get here. So if you’ll be so kind as to excuse the once-removed nature of this ‘dick’: Ishmael, the narrator of Moby-Dick, masterpiece of the grandfather of Gnostic Pulp himself, Herman Melville, who represents a more pluralist, or anthropological approach to the investigation.

Spiritual Gumshoe

While I earlier introduced the spiritual gumshoe as a literary figure, it is, in fact, a character type who inhabits our modern world in droves, but before we tackle this figure head on, I am noticing some fidgeting in the back, so let us take a short detour and see if we cannot apply some sort of balm to those with an allergy to the word spiritual. You are more than welcome to define spirituality as a sense of relating to, and feeling at home in, this world. In fact, one might argue that is its oldest meaning. Now, with the preceding definition of spirituality in hand, the spiritual gumshoe can be understood as nothing more than one who is seeking that feeling of being at home in this world. Surely everyone knows someone like this.

Sometimes called seekers, the spiritual gumshoe is unable to accept the lifeworld they were born into. When born into a hegemonic lifeworld such as our own, one that denies the validity of any alternative, exiting from the structure leaves the seeker totally unrooted, desperate, and lost. One day they have gone Buddhist, the next they are into crystals or bigfoot, then suddenly they are heading off to mass, all in pursuit of some ill-defined solace.

The spiritual gumshoe is neither a character strictly of the left, nor of the right, and often will consider themself apolitical. The spiritual gumshoe deals in width rather than depth, learning a little about a range of lifeworlds rather than finding a true home in any one. The spiritual gumshoe is deeply gnostic, believing that the revelation of some form of mystic knowledge will have a transformative effect not only upon themselves, but upon the world, which they consider, in some way, fallen. The spiritual gumshoe seeks transcendence above all else. The spiritual gumshoe tends to derive from a society that has cut its tethers not only to any form of natural religion (by which I mean the type that percolates out of a people’s direct relationship with the world, most often found in societies who do not have a word for religion), but in which the world religions that move in to replace the natural religions have largely lost their vitality, too. The spiritual gumshoe is left to the marketplace of spiritual pathways, a sort of shopping mall stocked with neatly labeled goods and bright overhead lights. In such a place, they may feel themselves to be more akin to the rats who come out at night to gnaw on the packages, digesting more cardboard than sustenance.

Black Iron Prison Break

Philip K. Dick could be considered the patron saint of spiritual gumshoes, and his Exegesis, the gumshoe’s holy book. PKD devoted his life to mapping the passageways of the underworld, refusing to settle for anything less than transcendence. He, too, was a member of the same lifeworld as myself, but he became estranged from it through a series of events which he came to refer to in shorthand as 2-3-74. This sequence of events is rather well known, and I will only give a brief summary here because it is so central to the deep spiritual gumshoery of Dick’s final years.

Something happened to Philip Kindred Dick in February and March of 1974. He was living in a rare instance of family-man-stability, staying in Orange County, California, with his wife and son. It began with a visit to the dentist to receive treatment for an impacted wisdom tooth. The doctor administered a general anesthetic. Later, after he had returned home, he was visited by a pharmaceutical courier delivering his painkillers. As he greeted her at the door, he was drawn to her necklace which she explained to him was a symbol used by early Christians.

In that moment, Dick experienced anamnesis, or the “sudden, discorporating slippage into vast and total knowledge”, and for weeks afterwards acted as the receiver of intense visionary experiences. He felt himself compelled to perform a home baptism on his son. He was visited by a “red and gold plasmatic entity”, and heard dire messages on his radio. He believed he was inhabited by a second personality, a Christian in ancient Rome named Thomas. Most famously, a pink beam of light warned Phil of a life-threatening condition concerning his son, and he rushed him to the hospital, where doctors confirmed the presence of a hernia that may well have proven fatal had it not been caught (Dick xiv).

Trying to figure out what happened to him during this time acted as the impetus behind the creation of his Exegesis, a thousand page doorstop of notes, letters, and journal entries cataloging Dick’s desperate search for meaning behind the events which had been enough to tear him from the reality structure which he named the Black Iron Prison, the roots of which he traced back to the Roman Empire.

With the dawn of the Empire, it was as if some continuum had been broken, forever altering the course of humanity. Like a dammed river, this new lifeworld has continued to grow while failing to move forward. It has eroded its banks and flooded into neighboring lifeworlds, forcing them into tributaries of itself. After two thousand years of metastasizing, what exactly the Black Iron Prison (BIP) is is difficult to say, for a lifeworld can only be seen from the outside.

Though it has not outwardly shed the dead skin of the nation-state, the BIP long ago outgrew this container. It has acted over millennia to infect a huge portion of the world, bursting out of southwest Europe to infest continents, getting into the bloodstream of modernity, the markets, as Gnostic Pulp extraordinaire, Thomas Pynchon, traces so well in much of his work, but most explicitly in Gravity’s Rainbow, in which there is more than enough dick talk to qualify it as an honorary third dick. A quick example: Tyrone Slothrop becomes a bit of a detective himself. While stationed in London during the Blitz, a certain pattern begins to reveal itself. German rockets fall in each place he previously had sex.

Dick bonafides established, a quest ensues. Slothrop seeks to discover the meaning behind this connection. His search brings him to postwar Germany, or The Zone, where his gumshoery reveals, as it is wont to do, something much darker than he had set out looking for. In a sense, he gets a grasp of PKD’s Black Iron Prison, which is expanding into its current form under the cover of WWII. Slothrop senses a structure without boundary that has transcended the usual notion of state or side. An ethereal, tendriled thing, operating in the shadows, the “terrible structure behind the appearances of diversity and enterprise” (Pynchon 165).

This raketen-stadt, as Pynchon names it, was to become the “city of the future where every soul is known, and there is no place left to hide…cutting across every agency, human and paper that ever touched it” (566). This structure, this synthetic demiurge that has claimed the world, had devotees on both sides of the war, and it was this alliance, which superseded any claim of nation, religion, creed, humanity, or even life itself, that propelled the BIP into the world’s first hegemonic lifeworld.

The nucleus of the Black Iron Prison is profit extraction. Look and see the true face move behind the corpseface of our lurching institutions. It is no wonder so many spiritual gumshoes are out in the astral planes, desperately seeking a new home, for our own is contaminated. If the BIP is a fallen world driven by profit extraction, it is a reality that renders the world into little more than a mine, storehouse, and market. One cannot live in a mine, storehouse, or market.

Compelled by the visit from something outside his own reality structure, PKD began a frantic quest to discover the origin, purpose, and weaknesses of his lifeworld. He tried out endless theories, most perfectly encapsulated by an exchange he has with God in which they enter into a sort of game, spurred by a challenge: “Construct lines of reasoning by which to understand your experience... I will enter the field against their shifting nature. You think they are logical but they are not; they are infinitely creative” (639). Dick then begins to lob theory after theory at God, only to have them batted back. It was this game of cosmic tennis that consumed the final eight years of his life.

He tweaks, dispels, vastly complicates and endlessly contradicts theory after theory throughout his search, so that there is no final PKD cosmology. There is our present world: the Black Iron Prison in which we are trapped, a fallen world with its roots in the Roman Empire. Then there is a certain point in the future which Dick refers to as Palm Tree Garden, or PTG, which is the spiritually redeemed and ontologically genuine world. The trick is to access what he names Ubik in order to move from one to the other.

We see here many rather obvious parallels with Christianity, which is intimately tied into Dick’s theorizing. After all, it was the light glinting off an ichthys that first awakened PKD to all of this. The similarities between Christ and Ubik are plentiful, and that Christ came to earth during the time of the Roman Empire is an inescapable synchronicity. Could it be that The Fall was nonuniversal? The Roman Empire was Fallen, in the Christian sense, because its people had lost their sense of being at home in the world. Was Christ, then, a gifted way back into the world, open to all who have fallen? Not the One Way, but a New Way? That gift, then, was not only rejected, but perverted by the demiurge, the prime directive that has taken control of the world of the Black Iron Prison. Movements such as Christianity could be seen as Ubikian signals meant to guide humanity towards paradise, but are now largely being operated as puppets of the Black Iron Prison.

BIP uses a distorted version of the medicine meant to dispel it to instead replicate itself, to invade and mutate neighboring lifeworlds, cancerously spreading The Fall, reaping disharmony and unrest worldwide, and installing markets and mines in the ruin. PKD spent a lifetime constructing models such as this and trying them out, demanding an answer from the heavens, only to tear them down and construct new ones. Again and again and again. This is the spiritual gumshoe way, seeking that transcendence which might save us all.

Temperance Aboard the Pequod

David E. Young and Jean-Guy Goulet are the editors of a fascinating anthology, Being Changed By Cross-Cultural Encounters. In this collection of essays, they explore lifeworld in its anthropological context, a view that accepts the “possibility that reality is culturally constructed and that instead of one reality…there are multiple realities - or at least multiple ways of experiencing the world, depending upon time, place, and circumstances” (8).

A lifeworld cannot be seen except from the outside, but it cannot be felt except from within. Anthropologists who have adapted to the lifeworlds of the people with whom they are living have reported extraordinary experiences such as their own native reality-structure cannot explain. These experiences, however, “take a form and content consistent with one’s host culture” (7). It is as if the anthropologist has entered a different reality, one where different rules apply.

The anthropological ideal of participant-observer gives the anthropologist a unique opportunity to move between lifeworlds without becoming untethered. PKD actually illustrates an understanding of this in his final entry in the Exegesis which explores the Yin-Yang dynamic. He writes that true existence requires experience of both. Yin is the incarnated side, limited and darkened, that being within a lifeworld. He saw this as himself, Phil. Yang, then, is the inbreaking force, the outside, the anamnesis, which he believed was Thomas, that other consciousness occupying his mind. Balancing the two requires a sort of angelic grace, akin to that illustrated in the Temperance card of the Tarot.

Temperance is depicted as an angel holding a chalice in each hand. While one is held higher, they are tilted towards one another, and it is as if the fluid from each is reaching towards the other, becoming braided with its opposite’s stream, and flowing in both directions through the air. The angel's wings could represent the ability to move vertically within a lifeworld, and the landscape upon which they stand, the horizontal freedom to move between lifeworlds.

As Young and Goulet, the Temperance card, and, soon, our second dick, suggest, mastery of this divine fluid exchange can give one the ability to exist fully within a lifeworld as well as the freedom to move between lifeworlds with ease. We see this again and again in Ishmael, the narrator of Moby-Dick, but perhaps never more clearly than in the spermaceti scene. Ishmael and the other sailors are assigned the task of “squeez[ing] these lumps back into fluid” (468). Ishmael loses himself entirely in the tactile nature of the work, which produces an overwhelming love for the physical chore at hand, the world at large, and his shipmates with whom he is performing the labor. At least momentarily, Ishmael feels his way into the world, escaping the Black Iron Prison and becoming enmeshed in a time-outside-of-time. In a sudden vision of heaven, he sees even the angels are lined up, squeezing spermaceti. This scene, then, includes the two major images of the Temperance card: the divine fluid and the angel, thereby signifying Ishmael as a master anthropologist.

In Moby-Dick, the BIP manifests microcosmically as the Pequod, for what is a whaling ship but a tool for mining whale fat? As we have said, one cannot be at home in a mine. Its structure forces a certain relationship, and that relationship is shaped by a subject-object orientation, as exemplified by the whaler’s weapon of choice, the harpoon. Like the miner’s pickaxe, a harpoon has a handle on one side so that it can be operated by someone, but the spear point can only be operated on something.

Once at sea, the Pequod herself becomes a harpoon. Her subscribed mission to harvest spermaceti, or the oil of sperm whales, becomes secondary to her monomaniacal captain’s desire to hunt Moby Dick. There is perhaps no better analog in all of fiction for PKD’s search than Captain Ahab’s. Something happened to Captain Ahab, you see. In a certain sense, it is analogous to the events of 2-3-74, which PKD eventually decides was an encounter with God (640). Ahab had his own encounter. The white whale tore off his leg in their only previous meeting. This experience massively shifted the purpose of his existence. No longer can he live a normal life. He must find the meaning behind the encounter, and enter into a final battle, so as to discover whether it had been an indifferent accident by a wild animal or a purposeful attack by an agent of a deeply meaningful world.

Ultimately, this is the seed that drives all spiritual gumshoes: a need to force God’s hand. Few, if any, accomplish this, and to fall into it ass-backwards is a terrible thing, as we witness in the story of Pip, who Ishmael describes as “the most insignificant of the Pequod’s crew” (465). While filling in as an oarsman on one of the smaller whaling boats, Pip jumps overboard from fear during a hunt, and is left behind, “bobbing up and down in the sea” (465).

Eventually, the Pequod happens across Pip, and he is pulled up, but while “the sea had jeeringly kept his finite body up, [it] drowned the infinite of his soul” (466). Believing he would die, alone, surrounded by such endless stretches of coastless water, Pip witnessed an incomprehensible vision of pure reality without the protecting lens of a lifeworld to give it shape, or, if you will, he came face to face with God:

Carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels then uncompromised, indifferent as his God (466-467).

Following this experience, Pip becomes rather useless as a sailor. The sailor formerly known as Pip has been transformed by his proximity to death and his unfiltered vision of God. For that reason Ahab, after hardly speaking a word to him for the majority of the text, suddenly feels a deep bond with Pip, for he has witnessed what Ahab so longs for. They have both had encounters with God, and each paid the price: Ahab a leg, Pip his mind.

In this context, the lifeworld can be considered a protective vessel rather than a prison. This paradox is addressed in the novel itself when the Pequod is portrayed as both hunted and hunter in a scene in which she pursues a pod of whales even as she herself is pursued by pirates (433). If the sea is unfiltered reality, then the Pequod offers a way to survive. It may be a demented whaling ship, but is that not better than drowning?

It is enough for Ishmael to make a home. Rather than the desperate seeking of PKD and Ahab, Ishmael settles into daily routine and makes fast friends with a fellow sailor named Queequeg. Queequeg is something of a microcosmic representation of a lifeworld outside the BIP. Ishmael sees in his new friend “a man some twenty thousand miles from home…thrown among people as strange to him as though he were in the planet Jupiter; and yet he seemed entirely at his ease” (Melville 77). In other words, Queequeg is at home in the world, and offers proof that a lifeworld, the BIP or otherwise, is less spatial than psychical. Despite his happy internal circumstances, Queequeg makes no attempts to evangelize, for his is not that kind of religion. It is of an older sort which swells out of a way of being in the world.

Queequeg is not an inmate of the BIP, but rather a member of a lifeworld that has inscribed his world with meaning as literally as it has inscribed itself onto his body via his sacred tattoos. It is an internalized thing, not intellectualized, but felt. Ishmael doesn’t have that. Though he calls himself a Good Christian, he is unsatisfied with it. Still, he seems blessed with an intrinsic understanding that he cannot think his way into Queequeg’s religion. Instead of pursuing the same chase as PKD, he opens himself up the best he can to the ultimate unknowable nature at the core of all things. In this way, according to philosopher Hubert Dreyfus’ brilliant interpretation to which my own owes a great debt, Ishmael becomes a sort of anthropological pluralist.

As opposed to the spiritual gumshoe who desperately seeks answers, the pluralist is able to become The Wanderer: a temporary devout at any altar, a master of every mood, the ultimate observer-participant, able to move in and out of lifeworlds, accepting that each one offers various glimpses which can then be harmonized, although never to an end. Like Lovecraft’s adjective-conglomerates, no full image of reality can be consummated, but, for one who is able to engage with the world at hand, it need not be.

The White Whale

In Pip’s vision, the spinning of the weaver-god’s loom creates a white noise by which the weaver is deafened. It is this very whiteness which Melville insists is the key to the book. Ishmael says that it is the “whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled [him]” (223). He fretted deeply over not being able to communicate the reason behind this terror, fearing that if he could not convey the dread then “all these chapters might be naught” (223).

White is the culmination of all colors, but its contributing qualities are made invisible by their amalgamation, making it a “dumb blankness, full of meaning” (231). However, a prism is capable of breaking apart that blankness and revealing the rainbow within.

Taken all at once, God/reality/the universe/whatever might well be an incomprehensible whiteness, the same sort of vision that drove Pip mad, for he looked on like a traveler upon the bleached landscapes of the ice smote north, where he who refuses to wear shades upon his eyes, “gazes himself blind at the monumental white shroud that wraps all the prospect around him” (Melville 231).

The anthropological pluralist does not demand this ultimate answer buried in the blinding white, but rather accepts the divine mystery at the heart of the universe. It is only those who insist on total understanding who ultimately chase a whiteness that is nothing but blinding. Each healthy lifeworld is capable of stretching a single color out of the vast emptiness. Though the majority of the spectrum is lost, a true aspect of God is made visible. Only closed, hegemonic lifeworlds blot out all the light, allowing not even a single color to shine through.

Let us poor inmates bow our heads and close with Melville’s prayer:

“Heaven have mercy on us all--Presbyterians and Pagans alike--for we are all somehow dreadfully cracked about the head, and sadly need mending” (110).

Works Cited

Dick, Philip K. The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick. Edited by Jonathan Lethem et al., Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Dreyfus, Hubert. Melville’s Moby Dick.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. Library of America, 2010.

Pynchon, Thomas. Gravity’s Rainbow. Penguin, 1973.

Rostocki, Adam. “Private Dick.” Private Investigator, 13 July 2021, www.private-investigator-info.org/private-dick.html.

Sloterdijk, Peter, and Rainer Maria Rilke. “Archaic Torso of Apollo.” You Must Change Your Life: On Anthropotechnics, translated by Wieland Hoban, Polity, Cambridge, UK, 2014, p. 21.

Sloterdijk, Peter. You Must Change Your Life: On Anthropotechnics. Translated by Wieland Hoban, Polity, 2014.