Further Adventures in Pynchonian Reality

Shadow Ticket, Thomas Pynchon, and the History of Tiki

This is not a Shadow Ticket review.

First of all, we here at Gnostic Pulp don’t know the first thing about writing traditional reviews which is why we prefer the term investigations. We walk the surface of a given work, dowsing with our witch sticks, divining just where to drill so that the living water of gnosis will rush upwards to fill our hollow well.

Secondly, it is too early for such an attempt. Even resident Pynchon expert,

elected only to give a “vibes-based review”. The professionals, meanwhile, have largely made fools of themselves with their hastily written nonsense. Kathryn Schulz writing for the New Yorker, used her column to complain that our “reigning artist of paranoid convictions…[didn’t] use...the present political moment to craft a satire or a survival manual or a swan song or even an ‘I told you so’.” As if a book about a world of emergent fascism with a rampant homeless crisis, populism without ideology, and a trade war looming in Asia has no relevance to our own just because it is not literally set in our decade.Pynchon’s choice of settings are generally considered to be something of historic windows, periods where history seems to sniff the fresh air of redemption before veering violently back onto the familiar, blood-greased tracks it has been running away on for some time now. In this way, he is never writing about “the times”, but rather the foundation upon which “the times” are built. His novels are freeze frames of ourselves collectively sticking a fork into the electrical socket so that our skeleton is briefly made visible.

They show us what is underneath the surface.

If such a revelation, most probably the last we will receive1, is not reason enough to celebrate, Shadow Ticket just so happened to drop the day before my birthday. I intended to honor the occasion. After getting the baby down for the night, I prepared to mix myself a beverage then sit back and enjoy the first several chapters. The only question that remained was what beverage best pairs with the literary event of the decade?

Pinky’s Tiki

Tom Pynchon’s Liquor Cabinet is a commendable project in which the host has committed himself to making and sampling every drink mentioned across Pynchon’s oeuvre. I might have saved myself the trouble and simply perused these pages until something sounded good. Alternatively I could have Let Go and Let God by hitting the gambling man’s Random Drink button at the top of the page, but Pynchon is not exactly the guy you go out with and tell the bartender “I’ll have what he’s having.”

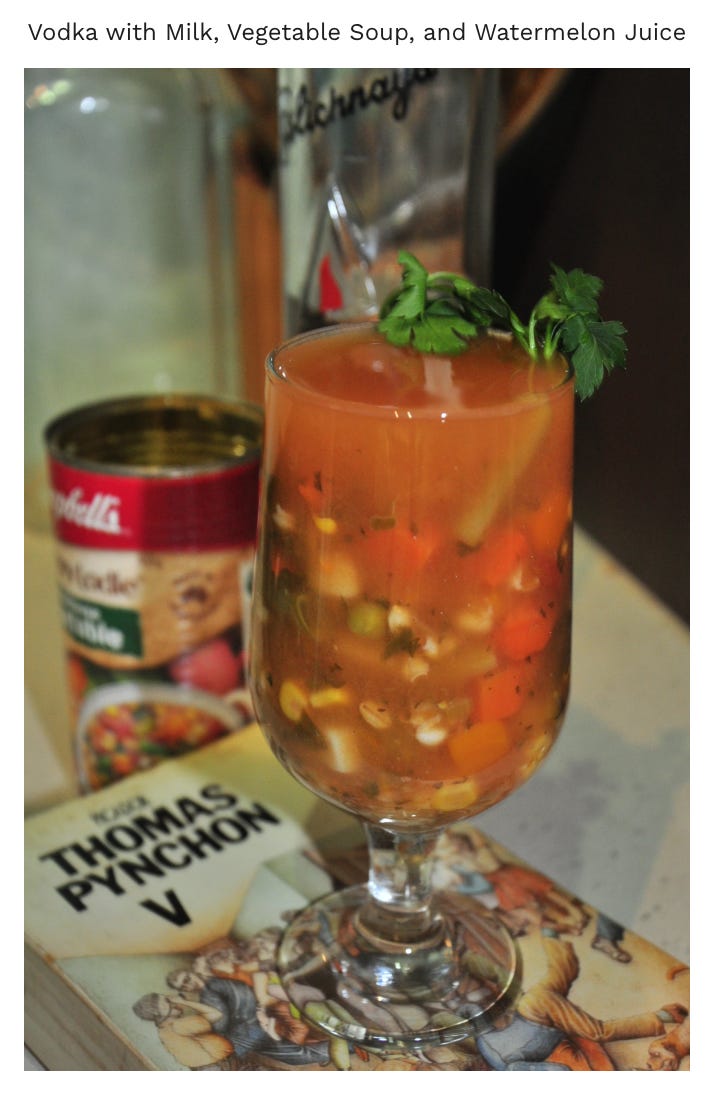

I only had to smash the random button two times before arriving at this monstrosity featured near the beginning of V:

As Meat Loaf sez, I will do anything for love, but I won’t drink that.

Besides, I just so happen to have a modestly stocked tiki bar in my backyard, and what could be more Pynchonesque than tiki, that chintzy American invention papering over centuries of horror?

Pinky’s Tiki, as we dubbed the place after our recently passed cat2, came to us somewhat by accident. There is a large outbuilding on our lot that the previous occupant had decked out as his woodworking shed. He mounted speakers on the ceiling, installed a window unit, and ran power throughout the whole structure. Neither my wife, myself, nor our baby knows the first thing about woodworking, so when we moved in we weren’t sure what to do with the space, and it came dangerously close to serving as the family dumping ground.

My mother, my sister, and my own family all moved at the same time. With my sister and hers relocating into an RV, they needed a place to store some of their furniture, including a mid-century bamboo set that her husband’s grandparents had brought over from Hawaii. Meanwhile, my mother was vacating the Texas coast where she’d been living for the better part of the last decade and had an abundance of beachy decor that would have been quite out of place in her new home in east Texas’ Pineywoods, so it all came to us and our big backyard storage shed.

With a little rearranging, some motivated thrifting, and a hefty purchase from the liquor store, we had the makings of a tiki bar on our hands, and it has grown into something of a hobby for myself who has spent the majority of my professional life either groveling away behind coffee bars or as a short-order cook. I enjoy working with food and beverage, and tiki is nothing if not highly involved drink recipes.

There were a few old standards I considered whipping up that would have been fitting. Hell, I had everything on hand for a Tequila Zombie, but I was feeling creative and wanted to come p with my own concoction.

Rum is, of course, the backbone of the tiki tradition, so it would have to serve as the base of my drink. It is also, without a doubt, the most Pynchonesque of liquors. Alongside its cousin, the Brazilian Cachaça, rum is the first American liquor. While popularly believed to consist of white, dark, and the cursed “spiced” rum, it’s actually got something of anarchist tendencies. Forget Captain Morgan’s and Malibu. With very little in way of regulation, the variation available within rum is immense. Listen closely at any tiki bar, and you’re likely to hear heated arguments over how best to categorize the stuff. Lives have been lost over inaccurate classifications. This is serious stuff.

And there’s a good reason for these complications: rum was born at the confluence of a half dozen streams of civilizations meeting in the New World.

Here is journalist Ian Williams writing on the topic:

“The original skills of Neolithic East Asian subsistence farmers, Greek and Arab science, early modern commerce, the Mediterranean abuse of slavery for sugar cultivation, and the Iberian discovery of Africans as readily available slaves were stirred with Protestant enterprise from England and Holland and the Celtic taste for strong liquor and skills in meeting their needs. Together, these streams of history all mixed in one small island to produce the heady cocktail of rum, which was to foment wars, industries, and revolutions around the Atlantic for centuries to come3.”

Just take a look at a random bottle and the dark history is likely to become apparent rather quickly. The origins are all former colonial holdings. Many bottles denote whether they are distilled via British, Spanish, or French methods. And until only last year, one of the staple brands was just straight up named Plantation.

It has since rebranded as Planteray.

I actually used a bottle of Planteray in the drink I came up with, which I named Banana Breakfast, adding to it a delicious toasted banana liqueur (in honor of Pirate Prentice, of course), some cold brew-infused bourbon (to emphasize the breakfast theme), and a few secret ingredients. The exact specs for Banana Breakfast are revealed to paid subscribers at the bottom of this piece, but everyone else is welcome to read on about tiki’s Pynchonesque history.

King Sugar

Although fermented sugarcane beverages date to prehistory in Southeast Asia, and sugar wine had found its way at least to Iran by the Middle Ages, what would pass for rum by modern standards has its origins in the colonial bloodbath of the seventeenth century Caribbean where sugar-making by-products, namely molasses and sugarcane juice, were first distilled.

That word, by-product, should send any good Pynchonista’s head spinning with sweet dreams of coal-tar, that by-product so central to Gravity’s Rainbow. Long considered waste, it wasn’t until IG Farben began alchemizing synthetic dyes out of the substance that its value was realized, and the black goo went on to become the artificial prism through which man produced his false rainbow. These days, coal-tar products are used in everything from roof pitch to mothballs, from plastic to the ointment I rub on my left elbow whenever my patch of psoriasis breaks out.

writes about how these products lie at the heart of Gravity’s Rainbow:“the forces at play create a world built from these substances, their precursors, their derivatives; what we have done and are willing to do to continue their extraction; what hidden worlds they have unlocked which should have always remained invisible to our eyes and our mind; why we do not need to live like this, why we should not continue to live like this.”

That second sentence is the ringer: What we have done and are willing to do to continue their extraction. It is a haunting line when applied to coal, and, as we shall soon see, equally so when applied to sugar.

The Portuguese brought large scale sugarcane cultivation to the New World in the early sixteenth century. In fact, Columbus had sugarcane roots in the ground as early as 1493. The plant, originating in Papua New Guinea, proved well adapted to the tropical climate where it could be grown year round, and its rearing spread rapidly throughout the equatorial region. The English, Spanish, French, and Dutch bought in, and within a couple decades thousands of sugarcane plantations covered the coast of northeast South America, from Santa Cantarina to Suriname, and then across the Caribbean islands, felling ancient forests, flattening mountains, decimating Indigenous populations, and terraforming vast swaths of mosaic life into monocropped hellscapes.

American sugar production quickly outpaced the exhausted capacities of Old World soils and sugar reigned as the most valuable American agricultural product for centuries. Eduardo Galeano, that rare poet-historian of the preterite, writes in Open Veins of Latin America:

“For almost three centuries after the discovery of America no agricultural product had more importance for European commerce than American sugar. Canefields were planted in the warm, damp littoral of Northeast Brazil; then in the Caribbean islands—Barbados, Jamaica, Haiti, Santo Domingo, Guadeloupe, Cuba, Puerto Rico—and in Veracruz and the Peruvian coast. . .Legions of slaves came from Africa to provide King Sugar with the prodigal, wageless labor force he required: human fuel for the burning. The land was devastated by this selfish plant which invaded the New World, felling forests, squandering natural fertility, and destroying accumulated soil humus.”

Growing sugarcane is intensive work, most profitably done at a large scale. To this end, the Indigenous of the region were forced into labor almost immediately, but they proved susceptible to European diseases. To sure up the labor force, millions of Africans were abducted, sold into slavery, shipped across the ocean, and forced to work in brutal conditions on the Europeans’ sugar plantations. There are no words to even approximate this undertaking. Together with the Indigenous Genocide, it forms the irredeemable sins undergirding the New World. There is no sense to be made from it.

Martiniquais author, Patrick Chamoiseau, writes in his novel, Slave Old Man:

“Since the arrival of the colonists, this island has become a magma of earth fire water and winds stirred up by the hunger for spices. Many souls have melted there. The Amerindians of the first times turned themselves into the writhing vines that strangle the trees and stream over the cliffs, like the unappeased blood of their own genocide. The slave ships of the second time have brought in black Africans fated to bondage in the cane fields. Only, it wasn’t people the slavers began selling to the béké planters, but slow processions of undone flesh…These creatures seemed, not to emerge from the abyss, but to belong to it forevermore. The colonists alone manipulate the carnal masses of this heaving magma” (6).

Then there is this stomach-turning one-liner from the Sugar plantations in the Caribbean Wiki entry that gets to the heart of the matter rather plainly:

Beyond the sheer violence against humanity, the local environment also paid a high price. As is always the case with colonial holdings, these places are not inherently poor, although the majority of people living in them are forced into abject poverty, if not outright slavery. In fact, these places are incredibly wealthy in natural resources, which is what makes them targets for colonization in the first place. It is only that they have their wealth stripped from them and shipped across the ocean to enrich the holders while receiving little more than mass immiseration and ecological ruin in return. Still, Pynchon is careful to point out that colonization is never a strictly economic affair. If it was, such short-term thinking in overproducing and depleting Caribbean soils would have been blasphemy as it was guaranteed to ruin future profiteering. There is something more insidious at work than mere economics, something in the colonists’ soul which takes joy in the cruelty itself:

“Colonies are the outhouses of the European soul, where a fellow can let his pants down and relax, enjoy the smell of his own shit. Where he can fall on his slender prey roaring as loud as he feels like, and guzzle her blood with open joy. Eh? Where he can just wallow and rut and let himself go in a softness, a receptive darkness of limbs, of hair as woolly as the hair on his own forbidden genitals. Where the poppy, and the cannabis and coca grow full and green, and not to the colors and style of death, as do ergot and agaric, the blight and fungus native to Europe. Christian Europe was always death. . . death and repression. Out and down in the colonies, life can be indulged, life and sensuality in all its forms, with no harm done to the Metropolis, nothing to soil those cathedrals, white marble statues, noble thoughts… No word ever gets back. The silences down here are vast enough to absorb all behavior, no matter how dirty, how animal it gets.”

Of course, it would be equally false to say the profit motive holds no importance, for it does remain the proprietary driver, but that second lens divorces the colonial mind from reality. The colonies become a no-place. The actions carried out there are meaningless, for they do not touch one’s reputation in the “metropolis”. This irreality is what allows for both the wanton cruelty and the aggressive agricultural output. No one would so freely destroy the productive soils of their own home, but when viewed as a no-place one is freed to farm as intensely and as greedily as one can.

The massive profits produced by this practice in the short term not only hugely enriched the land holders, but also spurred industrial growth in the imperial core. The vast influx meant sugar went from a luxury good of the wealthy to a staple available to all. Technology struggled to keep abreast with the surplus. Sugar mills went up everywhere and the cast iron fittings required to operate these mills were produced in Europe, sparking technological innovations that would go on to propel the first Industrial Revolution.

Europe's boon was Asia’s bust as this huge new provider of sugar had disastrous effects on growers there. Dozens of Chinese sugar traders went bankrupt leading to massive unemployment in the Dutch colonies in Indonesia. Gangs formed amongst the unemployed Chinese workers living in the colony. Spooked about an uprising, the Dutch cracked down, leading to rioting, and eventually the 1740 Batavia Massacre in which the Dutch East India Company massacred at least 10,000 Chinese workers.

Meanwhile back in the Caribbean, the enslaved people performing the dangerous, grinding labor that was causing such unrest on the other side of the world were living in their own exceedingly miserable conditions. As is reported in LibreText’s History of the Haitian Revolution, life in French Saint Domingue was exceedingly brutal:

“Slaves often dropped dead from exhaustion within three years of arrival on the plantation. The weather remained hot and humid at night, so the enslaved people had little recovery time in the sparse sleeping quarters they were allotted. During heavy harvests, enslaved people often worked for several days in a row with little, if any, rest…the majority of the enslaved people were only used for their labor until they could work no more. Plantation owners could have changed their practices, but the reduced profits would have exceeded the replacement costs of the enslaved people, so planters chose to work their enslaved people to death quickly and buy more.”

With plantation owners looking to pinch pennies even if it meant working their slaves to death, they were certainly feeding their workforce as cheaply as possible. Molasses, still considered a waste product at this time, formed part of their provided diet. It wasn’t until the mid-seventeenth century that the process for producing molasses-based rum was discovered in the British colony of Barbados. Its exact origin is unknown, but it is likely the discovery occurred among the enslaved, probably with the help of a Scottish or Irish indentured servant with some knowledge of the distillation process.

Thanks to its colonial connection with British Barbados, rum quickly took hold in New England where it became the preferred liquor, replacing whiskey which required valuable grain to produce. Once they got hooked, thrifty New Englanders began looking for cheaper sources of molasses, which they found in the French colonial islands. The British slapped a tariff on these imports, known as the Molasses Act of 1733, in an effort to force their subjects to Buy British, but instead wound up engendering a huge smuggling network and corruption among import officials.

The crown ended up losing money with the tariffs in place and was looking to walk them back by passing the now famous Sugar Act which actually lowered the original molasses tariff by half, but clamped down on smuggling. Resistance to this injustice helped unify the thirteen colonies who came up with the all-timer still known to school children across the country today: “No Taxation Without Representation!”

So did love of rum help spur the Revolutionary War? It certainly didn’t hurt. George Washington, that dastardly real estate schemer, counted the spirit among the staple rations required by his army, alongside beef, pork, bread, and flour. Paul Revere was most likely lit on the stuff when he clambered through town on his horse shouting “The British are coming!”

If rum played some part in the American Revolution, sugar production played a much more direct role in the Haitian Revolution. Known at the time as Saint Domingue, Haiti was a French holding in the Caribbean and sugar was its main export. In 1791, inspired by rhetoric from the French Revolution, Haitian slaves, led by Toussaint Louverture, revolted against their masters and gained their freedom, marking the only successful slave revolt in history, a success for which the old colonial powers are still making them pay to this day. In 1825, more than twenty years after winning their independence, the French sent warships to demand the young nation pay 150 million francs for the property lost in the revolution, in other words, for the loss of the slaves who revolted against them. The attitude towards this island nation has not improved much to the present day.

Nearly a hundred years would pass between Haiti’s independence and the freeing of the last slaves in the Caribbean. On October 74, 1886, Spanish Cuba finally got around to abolishing slavery. Only twenty-one years after that, the founder of tiki was born in Texas.

An Island of the Mind

Ernest Raymond Beaumont-Gantt is a character straight out of Pynchon. Like Anna Nicole Smith, he was born in Mexia, Texas, a small town suspended in the long stretch between Dallas and Houston. Mexia enjoyed, for a short period, prominence as a commercial crossroads for the farmers of the region and then spent a few decades as an oil boomtown. These days it is bypassed by the interstate and its population has dwindled to less than 7000.

Doesn’t sound like the most fertile grounds for the birth place of tiki, but Gantt didn’t spend a lot of time there thanks to his Grandpappy who apparently needed a young sidekick for his business ventures down in Kingston. By the onset of prohibition, Gantt was already an old hand at smuggling Jamaican rum into New Orleans.

After spending his teenage years rum running the Caribbean, and getting up to who-knows-what in New Orleans under, one has got to suspect, Grandpappy’s less than watchful eyes, Gantt accepted some money from his parents and cleared out. About as far out as you can clear. He spent the early Depression years bouncing between Hawaii, Australia, and the islands of the South Pacific, collecting souvenirs and immersing himself in the cultures and traditions.

“By 1931, Ernest was just twenty-four and back on American dry land, in Los Angeles, dragging a cargo of flotsam behind him: masks, carvings, and sundry Polynesian and nautical bric-a-brac. But he didn’t have a penny to his name. He started taking odd jobs—dishwasher, bus boy, valet. It was while working as a valet that he began to meet celebrities…and soon found himself hired on as a ‘technical consultant’ on low-budget films. Ernest’s bits and pieces of Polynesian ephemera, scattered around a set, could make the beach in Santa Monica look vaguely like Tahiti for that thrilling new serial” (Cate 26)

The South Seas had long held sway over the American imagination, thanks, in part, to the writing of Herman Melville and others. Vaguely tropical nightclubs, such as Hollywood’s Cocoanut Grove, had been popular since at least the early twenties—one even makes an appearance in Shadow Ticket, all the way out in Budapest. These were elegant places, frequented by the upper crust, featuring large dance floors, big band entertainment, faux palm trees, and dazzling experiences, but the drink menu was the usual affair, and there were certainly no pagan tikis.

Gantt squirreled away the money he made renting out his South Seas swag, and eventually had enough to acquire a little 13’ x 30’ room in Hollywood. He took the idea of the swanky tropical club, down-sized and -classed it, squeezing all his crusty decor into the tiny space, while still finding room for twenty-four seats and a bar, behind which he “hung a hot plate on the sill to whip up a little stir-fry for hungry guests” (27). Happy with his work, he hung a sign out front reading Don’s Beachcomber, reclaiming for himself the old pseudonym from his rum running days, Donn Beach.

Donn’s biggest innovation, however, was the drink menu. The Beachcomber launched such classics as the Zombie, Cobra’s Fang, Three Dots and a Dash, Navy Grog, and a dozen more. The venture was a huge hit, and soon inspired copycats.

Victor “Vic” Jules Bergeron, Jr. joined the movement only a year later. He was the owner and operator of a hunting lodge-themed joint in Oakland named Hinky Dinks, but after a trip down to visit The Beachcomber in LA he made something of a pivot.

“There was no fanfare about the opening. Just closed one day as Hinky Dinks selling sandwiches and opened the next day as Trader Vic’s selling tropical drinks and Chinese food” (34).

Vic took Gantt’s idea and expanded upon it. He hadn’t lived quite the swashbuckling life that Gantt had, but he did have a prosthetic leg from a childhood tussle with TB, and the good mind to spin tall tales about its origin. Gussying things up was Vic’s modus operandi. His foray into exotic cocktails ushered in the over the top drink ware that is now a mainstay in tiki culture, but his major claim to fame was the creation of the Mai Tai, perhaps tiki’s most popular beverage. Today, it is widely bastardized at bars outside the tiki tradition, and even safe within the confines of a proper tiki establishment arguments about the best Mai Tai recipe are likely to get as heated as those about rum classification.

By the 1960s, there were twenty-five Trader Vic’s locations across multiple continents. Vic had taken Gantt’s original concept and made it not only into a business empire, but an entire subculture.

Modern day tiki legends and owners of Smuggler’s Cove, Martin and Rebecca Cate, call the rootless nowhereland at the heart of tiki an Island of the Mind. It is a place of total fiction, manufactured out of disparate parts, some of them quite sacred, such as in the case of the namesake which originates in New Zealand and the Marquesas Islands where they are carved as representations of the first man, gods, or as symbols of procreation, depending on origin and specifics. In its appropriation, the tiki has come to describe any exotic “carving with a largely human form, exaggerated features, and a menacing visage (36)”. Some bars are apt to apply their own legends to these idols, treating them like tropical Dionysuses, thereby ensouling who knows what manner of egregores.

Other staples, such as rum, are pulled from the opposite side of the world as the tiki and have their own blood-soaked histories, as we have seen. These are thrown together with some mid-century mood music, or “exotica”, alongside a range of symbols ripped from their context and made to represent some idea of island living: from surf aesthetics to thatch roofs, topless women, nautical detritus, sea life, etc, resulting in a totally manufactured kitsch. And the snowball keeps rolling. Tiki’s appropriation knows no bounds. It will suck up foreign religions and Caribbean drinks as readily as pop culture and the paranormal, The Creature of the Black Lagoon and cryptids having become tiki mainstays. Old school country music, SpongeBob, punk, aliens, goth aesthetic, Scooby-Doo, it is all fair game to this escapist blob.

Barry Egan’s line from Punch-Drunk Love (“It really looks like Hawaii here”) might readily apply within the confines of any tiki lounge. Of course, Barry is literally in Hawaii when he speaks this line, but he is staying at an expensive resort that is playing at the same game as the tiki bar, just on a much grander scale. Both are creating false representations that replace the originals. The Hawaii Barry is seeing is the one he has been groomed to see, but it has all been manufactured. This map-for-the-territory theme is well trod, uh, territory in Pynchon, especially in Inherent Vice, the most tiki of Pynchon novels.

The schtick was sold by a couple extraordinarily charismatic entrepreneurs to a bunch of broke, depression era preterite who’d hardly seen the other side of town, much less the other side of the world. They imagined for them an island paradise of wonder and mystery. Authenticity has never been the name of the game. Tiki is all about spectacle. People go to a tiki bar because they want to be wowed into forgetting, for the length of an evening, whatever it is they came in out of.

Ultimately, tiki has found such lasting success in the United States because the USA is tiki, an appropriated conglomerate of schlocky kitsch plastered all over with symbols of the once sacred, totally dependent on a patine of inebriation and a lack of critical attention in order to hold itself together. Believe me, when the crowd leaves and the overhead lights come on at Pinky’s, all the magic is gone, and I find myself standing in a cluttered plywood shed in my own backyard, with a huge tub of dishes to get to and a hangover already coming on.

The Drink

Below are the specs for Banana Breakfast, in my opinion the best of my own short list of contributions to the tiki recipe book. As I warned above, the recipe is available only to paying subscribers, so join up now and may this elixir coat all the booze-corroded stomachs of Substack—

banana appétit!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Gnostic Pulp to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.