There is an inhuman will at the helm of this vessel, and we are all at its mercy. Such were the conditions Herman Melville’s ambiguously named protagonist entered into when he stepped aboard a whaling vessel called the Pequod, and gave rise to the particularly American genre of fiction which can be referred to as Gnostic Pulp. Beneath this wide umbrella are sheltered many revered names, but this series will be focused on Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick (1851), Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow (1973), and Ursula K. Le Guin’s Always Coming Home (1985). Taken together, these three novels form a trilogy capable of tracing the trajectory of the Black Iron Prison* from its nascent days, through the present, and beyond its ultimate demise.

*A term coined by another writer working deep in the same Gnostic Pulp vein, one Philip K. Dick. It refers to the world in which the Roman Empire never ended. In the glossary of his Exegesis, it is defined as: “the prison world of political tyranny and determinism…He later wrote that upon perceiving it, he realized that he had been living in it and writing about it his whole life” (919), as are we all.

Fittingly, this trilogy begins on the eastern shores of the United States. Ishmael, or at least that is what we are told to call him, is bumming around New York City, feeling “a damp, drizzly November in [his] soul” (25). Whenever such a depression grips him, he takes to sea: a cure he prescribes to almost all men. Thus might kick off any maritime adventure novel, popular at the time, but whereas most pulp fiction would center on the adventure, Melville takes for his focus the very longing that drove Ishmael to the sea in the first place.

Setting Sail

As Hubert Dreyfus says in his lecture, upon whose foundation much of my own theory has been built, “the land is solid and marked off. The sea is indefinite. The howling gale of the infinite.” Setting off into such boundlessness should not be taken lightly. Those men who undertake such a journey are driven by a longing. For some, such as first mate Starbuck, it is the rational pursuit of a living. For others, it is the call of adventure. For Ishmael, it is an almost suicidal depression, “this is my substitute for pistol and ball,” he confesses in the first paragraph (25). His is an abstract longing for the mending of some sort of interior wound which he seems especially attuned to, though implies is present in all.

Captain Ahab’s desire, meanwhile, is a harpoon. He has a precise, pointed mission: to find Moby Dick and kill him. Once at sea, the Pequod herself becomes Ahab’s harpoon: her subscribed mission to harvest spermaceti, or the oil of sperm whales, secondary to her monomaniacal captain’s desire to hunt Moby Dick. The other men onboard become entrapped in the machinations of this inhuman will to “chase [Moby Dick] round Good Hope, and round the Horn, and round the Norway Maelstrom, and round perdition’s flames...to chase that white whale on both sides of land, and over all sides of the earth, till he spouts black blood and rolls fin out” (196).

While, yes, the white whale did tear off Captain Ahab’s leg in their previous encounter, what drives his longing with such ferocious vitality is not a mere eye for an eye brand of ethics. When the Pequod happens across the English ship, the Samuel Enderby, Ahab meets with her captain, a man who also lost a limb in an encounter with The White Whale, but one who has no interest in facing him again. “Ain’t one limb enough?” he asks. And after learning of Ahab’s intentions, asks one of the seaman, “Good God!…Is your Captain crazy?” (494-495).

Crazy? Is it crazy to believe that “all visible objects…are but as pasteboard masks” (197), behind which lurks “the inscrutable thing”? Without this inscrutable thing, as Aaron Gwyn and Brad Kelly humorously point out in their Method & Madness podcast, Moby-Dick becomes Jaws (1975). Ahab does not want to just kill a fish, he wants to punch through the white mask, and reveal the universe mockingly lingering behind it, so as to discover whether he lost his leg through an indifferent accident caused by a wild animal, or via a purposeful attack by an agent of a deeply meaningful world.

The Black Iron Prison

While this project tends to have more interest in a gnosis of the broader sort, we are here going to devote some attention to capital-G Gnosticism, that ancient school of religious systems unified by belief in a transcendent God, or order of being, who exists in a realm beyond the material, but who is not the being behind the creation of the universe. That was the work of the demiurge, or Demiurgos, which is taken from the Greek for half-maker, called so for using “the already existing divine essence and fashion[ing] it into various forms” (Hoeller). The demiurge is said to be “totally ignorant of the Divinity from which he has fallen” (Wilson 202), and believes himself to be the ultimate power. However, the divine essence still exists within creation, so that something within us “rejects this false world, and longs for its true home” (202).

Whether taken as theology or metaphor, such a pattern can be mapped with happy success onto any system driven by an engine other than the greater good, such as a ship captained by a mad man hellbent on killing a particular whale, or perhaps a totalizing socio-economic system driven by a single Prime Directive: profit extraction. Those caught within such a machine find themselves as inmates in the Black Iron Prison.

While Ahab can be read at one level as the villainous demiurge, the evil will at the helm of the world of the Pequod, he is at the same time a citizen of the world at large, an inmate in the Black Iron Prison, a victim of the true demiurge, prodded on by his own need for redemption, as when the Pequod is both pursuing a large herd of whales, and at the same time being pursued by pirates. Standing on deck, Ahab “in his forward turn [beheld] the monsters he chased, and in the after one the bloodthirsty pirates chasing him” (433), so that he becomes both monster and hunter, predator and prey, warden and prisoner.

Ahab as prisoner is not quiet. Rather, he is determined to force God’s hand, desperate to discover whether the incident that led to the loss of his leg had been accidental or purposeful. Is the world random or full of meaning? This is a question the world of the Black Iron Prison cannot provide a satisfactory answer for, and that is the source of both Ishmael and Ahab’s longing.

Ahab as warden is enflamed with a dark charisma. His will controls the ship by some power greater than his rank. All the men onboard, even rational Starbuck who sees the madness in his captain, are powerless to stand against the draw of his quest: “My soul is more than matched; she’s overmanned; and by a madman!…he drilled deep down, and blasted all my reason out of me! I think I see his impious end; but feel that I must help him to it” (203), and so many men are held prisoner, sworn to a dark charisma, not just for the doubloon nailed to the mainmast, but by the drunken lure of destiny.

Meet Your New God: Profit Extraction

“Suspended in those watery vaults, floated the forms of the nursing mothers of the whales, and those that by their enormous girth seemed shortly to become mothers. The lake…was to a considerable depth exceedingly transparent; and as human infants while suckling will calmly and fixedly gaze away from the breast, as if leading two different lives at the time; and while yet drawing mortal nourishment, be still spiritually feasting upon some unearthly reminiscence;—even so did the young of these whales seem looking up towards us, but not at us, as if we were but a bit of Gulf-weed in their new-born sight” (437-438).

Into this serene vision flies another whale, one escaping the hunt, impaled by a harpoon and trailing a cutting spade, which, in his frantic fright, he churns through the water, “tossing the keen spade…wounding and murdering his own comrades” (440). It is a nauseating scene of pointless destruction made possibly only by the hunt, by the translation of whale from ocean creature to product on the market. A similar violence plays out anytime this translation is forced.

Among the first Europeans upon the North American continent were refugees, fleeing not only religious persecution, but a complete upheaval of their world. The sixteenth century wrenched Europe into modernity. Such turmoil was spurred by decimating waves of the Bubonic Plague which acted as a scythe, clearing the lands of its population, and forcing a new mode of production. In the midst of this violent reorganization came widespread war, intense urbanization, religious schisms, the collapse of the feudal way of life, and the birth of modern capitalism (Aubin et al).

New Christian movements arose trying to synthesize their faith with this new world which made the Christian ideal of universal brotherhood an impossibility, for “property ownership alienates man from God in such a way that it guarantees human relations are filled with strife, violence, lies, domination” (Christman). These movements, which arose both in Europe and in the North American colonies, included the Diggers, the Shakers, and later on the Mormons, who each attempted to reconcile the ideals of their faith with the new transactional relationships humanity had entered into with itself and the world at large. Many of the new protestant sects tried to fight this by living communally, such as the Shakers, who “by 1793 had made property a consecrated whole” (“Shakers”).

On coming across the Jeroboam, another Nantucket whaling ship, Ahab receives a dread omen from a Shaker prophet. Gabriel, who moves like a holy man outside of the regular hierarchy aboard his own ship, ignores his captain to issue Ahab a prophecy, declaring that he will meet his death in chasing after Moby Dick, “pronouncing the White Whale to be no less a being than the Shaker God incarnated” (361).

Ahab’s desire is not just to kill a whale. It is know Moby Dick, to map his contours, thereby turning him into an object, and therefore property. For that blasphemy, the Shaker God shall issue his punishment.

“In life the visible surface of the Sperm Whale is not the least of the marvels he presents. Almost invariably it is all over obliquely crossed and re-crossed with numberless straight marks in thick arrays, something like those in the finest Italian line engravings…These are hieroglyphical; that is, if you call those mysterious cyphers on the walls of pyramids hieroglyphics, then that is the proper word to use in the present connection. By my retentive memory of the hieroglyphics on one Sperm Whale in particular, I was such struck with a plate representing the old Indian characters chiseled on the famous hieroglyphic palisades on the banks of the Upper Mississippi. Like those mystic rocks, too, the mystic-marked whale remains undecipherable” (350).

Ahab’s longing to not only see God, but to know His essence are sins punishable only by death, which is, indeed, what awaits Ahab in his final meeting, but not merely death. He becomes entangled by netting and attached to Moby Dick, absorbed into him, and dragged into the boundless waters that are the whale’s home and the hunter’s doom.

Radical Mystery

Ishmael’s longing takes him in an entirely different direction. Dan Beachy-Quick, in his beautiful exploration of the novel, A Whaler’s Dictionary, notes that Ishmael has an innate understanding that “in the reflection of our face on water we seem to see the vast secret of our own lives, [but] the consequence of trying to grasp this self-secret is drowning” (168).

This secret, this inscrutable thing Moby-Dick is so rife with, is akin to what the Weird Studies podcast terms Radical Mystery. In an introductory essay on the topic, host Phil Ford defines it like so: “Radical mystery holds that mystery is not merely a contingent flaw in the state of our understanding, some lapse in knowledge to be supplied at a later date. Radical mystery asserts that the unknown — the hidden, the obscure — is not a lack at all but a positive and unexpungeable quality of things and events.”

This is not an idea that co-exists easily with the world of the Black Iron Prison, that world of determinism in which every thing must be neatly labeled, so as to be assigned value and position. Whaling ships are emissaries of the Black Iron Prison, sent unto the boundless waters in order to apply its rationality. With the conquest of the New World, the Prison had largely colonized the land, a mission which, too, once seemed impossible. At the time of the publication of Moby-Dick, the gears were in motion, technology simply had to catch up, and the further corners of the map brought into line.

What Melville understands, and the machinations of the Black Iron Prison cannot, is that the more something is examined, the more it opens up. No cetology textbook could capture a whale. Science, alone, can only make the whale stranger. Something, perhaps the original divine essence, will always escape. Moby-Dick demonstrates that Radical Mystery cannot be captured or nailed down. “It can only be lived. It is always present, thinly veiled by the business of existing until it suddenly breaks through in the least philosophical moments of our lives” (Martel).

Ishmael says that he has“perceived that in all cases man must eventually lower, or at least shift, his conceit of attainable felicity; not placing it anywhere in the intellect or the fancy; but in the wife, the heart, the bed, the table, the saddle, the fire-side, the country” (469). Perhaps most importantly of all, it is Ishmael’s engagement of what Colin Wilson calls Faculty X, or humanity’s “desire to make contact with reality” (58), as opposed to Ahab’s need to punch through the so-called mask of reality, that allows him to survive within the fallen world of the Black Iron Prison.

Shine On You Crazy Ishmael

Before the spread of evangelical world religions, most People did not have a name for the concept. Religion, then, was simply a way of being in the world. It arose naturally and instilled a sense of meaning in everyday life. Ishmael gets a glimpse into this way of being through his dear friend Queequeg, who I wrote about in an earlier post.

Ishmael cannot quite accept the Christian religion of his countrymen which seems to him a “hollow courtesy” (77), but he is deeply intrigued by Queequeg who seems totally at home in the world, even when so far away from his native land.

“But what is worship?” Ishmael asks, having walked out of a church sermon, unfulfilled, to join Queequeg in worshiping his wooden idol, Yojo, in their shared room. It is “to do the will of God — that is worship. And what is the will of God? — to do to my fellow man what I would have my fellow man to do to me — that is the will of God” (79), but, as we have said, this dream of universal brotherhood is being pushed out of the world in the time of the novel and replaced by the transactional relationships of the Black Iron Prison. How can one do unto their fellow man while living estranged from her? Under the regime of the Black Iron Prison, humanity lives connected largely by market relations, a rationale which encourages a pyramid scheme of transactions rather than anything like universal brotherhood.

Still, unperturbed by such happenings upon the material plane, “the weaver-god, he weaves!” (556), and the loom upon which he weaves joins the rainbow as the two great symbols uniting this trilogy. Pip, the lowliest member of the Pequod, happens upon a vision of this loom when he goes overboard during a whale hunt:

Carried down alive to wondrous depths, where strange shapes of the unwarped primal world glided to and fro before his passive eyes; and the miser-merman, Wisdom, revealed his hoarded heaps; and among the joyous, heartless, ever-juvenile eternities, Pip saw the multitudinous, God-omnipresent, coral insects, that out of the firmament of waters heaved the colossal orbs. He saw God’s foot upon the treadle of the loom, and spoke it; and therefore his shipmates called him mad. So man’s insanity is heaven’s sense; and wandering from all mortal reason, man comes at last to that celestial thought, which, to reason, is absurd and frantic; and weal or woe, feels then uncompromised, indifferent as his God (466-467).

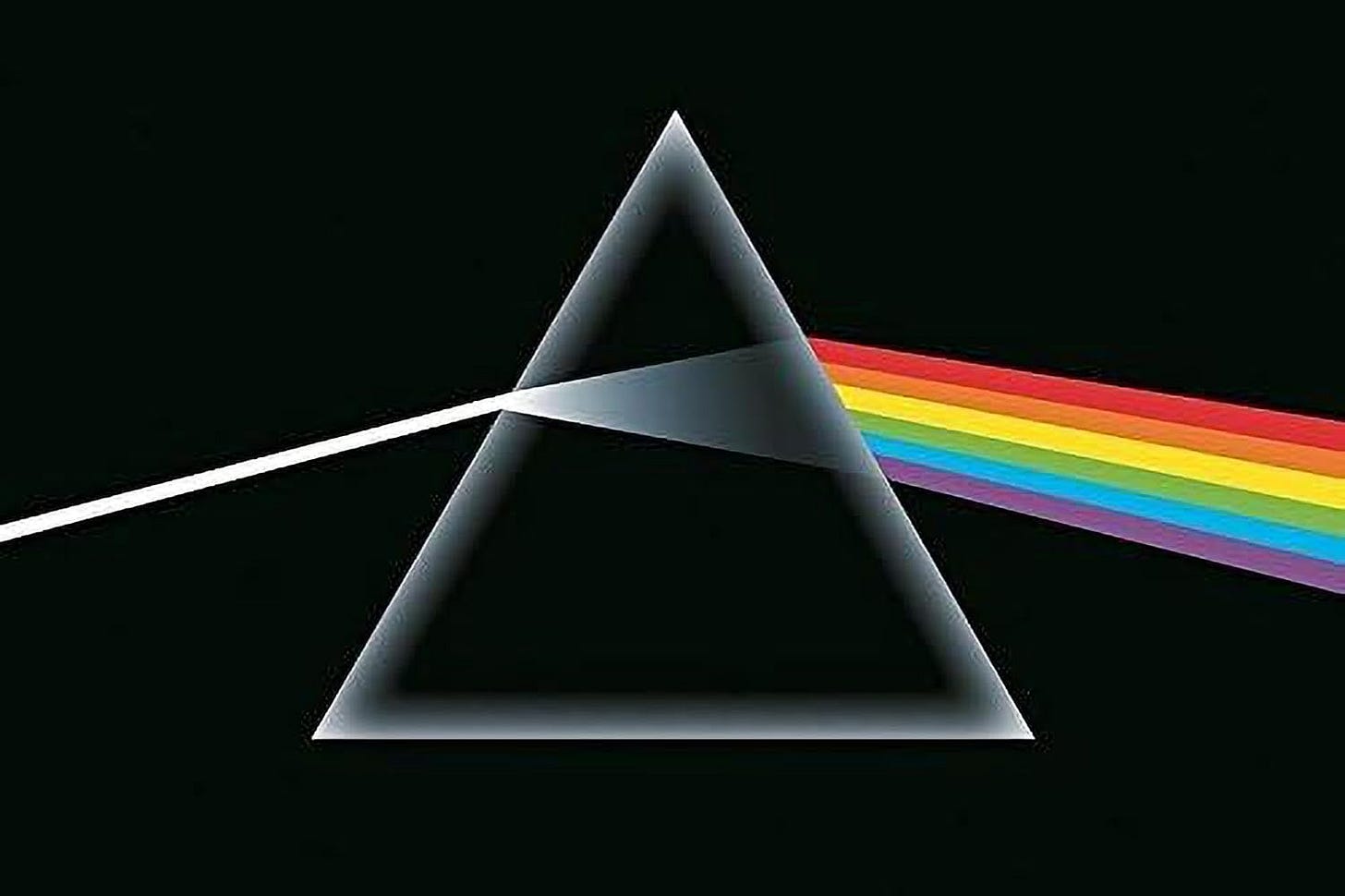

If God is both everything, “and totally beyond everything we mean by existence” (202), as Colin Wilson writes in The Occult, then what can we compare God to but white light? which, as every Pink Floydian knows, is the accumulation of all color. Stretching this metaphor to its ultimate limit, it can be said that each religion is like a single color plucked from this compact of white, and while the vast majority of the spectrum is lost, a true aspect of God is made visible.

The Black Iron Prison blots out all light, creating a fallen world, but, beyond the reach of its shadow, in the Remote, Wild, Watery, and Unshored regions of the ocean, drops of water suspended in mid-air act as prisms when pierced by beams of sunlight: “How nobly it raises our conceit of the mighty, misty monster, to behold him solemnly sailing through a calm tropical sea; his vast, mild head overhung by a canopy of vapor, engendered by his incommunicable contemplations, and that vapor—as you will sometimes see it—glorified by a rainbow, as if Heaven itself had put its seal upon his thoughts” (423).

Ahab’s inability to appreciate such a vision, his harpoonery, his monomaniacal need to spear God, to stare into the whiteness, inevitably leads to his death, and not only his death, but also the destruction of the Pequod, for it is his will steering the vessel. Ishmael is able to survive the destruction by floating on Queequeg’s coffin. The Black Iron Prison may be trying to push out Queequeg’s way of life, but it is lessons from this lifeworld that enable Ishmael to survive in his own with his humanity intact. Beachy-Quick writes that Ishmael “walks to the harbor under the command of the idol god Yojo, to whom he and Queequeg prayed the previous day” (201). This is what Dreyfus calls Ishmael’s polytheism at work: his ability to become a master of every mood, a devout at any altar. He is the prism capable of separating white light into the rainbow’s spectrum.

Colin Wilson’s concept of Faculty X might be thought of as a modern day version of this latent ability within all of humanity. When engaged, Faculty X allows one to enter fully into whatever act is at hand. Ishmael experiences this being in the world most vividly during a strange episode of working with spermaceti. His task is to “squeeze these lumps back into fluid” (468), and he loses himself in the tactile nature of the work, which at times becomes almost erotic and produces an overwhelming love for both the physical chore at hand, the world at large, and his shipmates with whom he is performing the labor.

What Wilson describes as an almost impossible longing, similar to the swell of feeling when observing a wondrous landscape, a feeling for which there is no correlating action, Ishmael is able to actually fulfill, at least momentarily. He feels his way into the world, escaping, for a time, the Black Iron Prison and becoming enmeshed in the moment to the point, that in a sudden vision of heaven, he sees even the angels are lined up, squeezing spermaceti.

Next Time

The exploration of the Gnostic Pulp Trilogy continues with Gravity’s Rainbow, in which the harpoon becomes the rocket, and The Black Iron Prison becomes endemic; we trade out Ishmael for Slothrop, and Ahab for a global cartel of Nazis, American business interests, and the controlling logic of capital.

Works Cited

Aubin, Hermann, et al. “History of Europe.” Brittanica, 18, Oct. 2022,

https://www.britannica.com/topic/history-of-Europe.

Beachy-Quick, Dan. A Whaler's Dictionary. Milkweed Editions, 2008.

Christman, Matt. “Grill Stream.” Let the Bodies Hit the Space, Episode 235, Apple Podcasts, 30,

Dick, Philip K. The Exegesis of Philip K. Dick. Edited by Jonathan Lethem et al., Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2012.

Dreyfus, Hubert. Melville’s Moby Dick.

Ford, Phil. “Radical Mystery: A Preliminary Account.” Patreon, Weird Studies, 24 Mar. 2022, https://www.patreon.com/posts/radical-mystery-64180412.

Hoeller, Stephen A. “The Gnostic World View: A Brief Summary of GnosticismS.” Gnosis.org, http://gnosis.org/gnintro.htm.

Hyde, Lewis. Trickster Makes the World, FSG, New York, 2010.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick, HarperCollins, New York, NY, 2017.

Martel, J. F. Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice, Evolver Editions, Berkley, CA, 2015, p. 22.

“Shakers” Wikipedia, 13 Jan. 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shakers.

Wilson, Colin. The Occult: A History. Vintage Books, 1973.