Safe When Used as Directed

On Philip K. Dick's 'Ubik'

“A synthesis higher than anything I have ever seen before: the spirit—the finest parts—of Marxism, Christianity, Buddhism—and yet it is above all this; and out of me it draws the most noble drives and aspirations, the mystical and the urgently practical combined.”

-Philip K. Dick (Exegesis 893).

It is summertime here in Texas, and, while we have had a somewhat mild June, 30+ years experience tells me July and August will be brutal. The heat sometimes seems to have an effect on time itself. By late afternoon, as it reaches its long zenith, parking somewhere in the low triple digits and waiting with predatorial patience, nothing moves, not even the shadows. A slight shimmer jumbles the air, but that is just the heat bending the light as the sun bakes down; pray God you are watching from behind a window. There is such a pressure applied from overhead that nothing can breathe. To try to cut through this scene, even a short distance, say from the front door to the car in the driveway, immediately saps your energy. Distances expand. The poor car’s air conditioner must exert itself terribly against the pocket of heat that has swollen up within. As soon as the engine cuts off, the heat expands, reclaiming its rightful territory.

Just two summers ago, BBC posed the question: Will Texas become too hot for humans?, so it is without much exaggeration that I say Some summer days it feels as if the world itself is coming apart. Maybe not in quite the same way as in Phil Dick’s Ubik, but in a similar enough way that I can imagine no better time or place in which to read this particular novel.

Slapdash Writing

PKD is not often lauded for his prose stylings, and I will here make no attempt to swim against the critical tide except to say, for us Dickheads at least, that slapdash writing is a feature, not a bug. The man was pumping out multiple novels a year while doublefisting amphetamines and canned dog food as the universe beamed rays of gnosis into his forehead. He sure as hell didn’t have time for multiple drafts. He had things he had to get down on paper lest they disappear. That a good few of his characters appear paper thin, and his worlds sometimes barely held together with glue, actually compliments his subject matter quite well, especially here in Ubik.

Published in 1969, Ubik reads like two different books struggling for dominance. Whether the sharp narrative turn which occurs about a third of the way through was an authorial choice, or the inevitable degradation, attenuation, and noise that must interfere with a signal broadcast through time and space in order to reach Dick and be transduced into literature is up to the reader to figure out.

Either way, Ubik takes place in a 1992 in which humanity has not only colonized the moon and invented a way to stave off death by placing the recently deceased into a form of cryonic-suspension known as half-life, but also applied a subscription-based service model to everything imaginable, including your own front door, which must be fed coins in order to open.

The protagonist of this world is another one of Dick’s broke-and-horny, working-class everymen, one Joe Chip. We are introduced to Joe in one of my all-time favorite Dick scenes. He’s hungover, in his apartment, feeding coins to his rented ‘pape machine in order to read the gossip column. Then he spends his last dime to start up his coffee maker meaning he does not have the money necessary to open his own front door when a visitor arrives. Not only that, but the door becomes smug, almost mocking, and then threatens to sue when Joe begins to take it off its hinges.

Such indignity is now matched daily in our own fallen world where one might find themselves logged out of their own toothbrush.

We are soon shown that it is Joe’s own fault he is so broke. It seems he does have a good job, working as a tester for a prudence organization called Runciter Associates, owned by Glen Runciter, but he lives in a world that is totally saturated by advertisements and he can’t help but blow all his money as soon as he gets it, largely on luxury items such as authentic Kenyan coffee. As a tester, his duty is to investigate the powers of potential inertials, or individuals with the ability to negate the powers of telepaths and those with precognition, or precogs.

These organizations, such as Runciter Associates, appear profitable, but sleazy. They consult the dead about advertising strategies, run hourly televised ads, and generally ratchet up paranoia in order to turn a profit.

“Telepathic phenomena, having been mastered in the context of capitalistic society, have undergone commercialization like every other technological innovation. So businessmen hire telepaths to steal trade secrets from their competitors, and the latter for their part defend themselves against this ‘extrasensory industrial espionage’ with the aid of ‘inertials’, people whose psyches nullify the ‘psi field’ that makes it possible to receive others' thoughts. By way of specialization, firms have sprung up which rent out telepaths and ‘inertials’ by the hour.” -Stanislaw Lem

Lately, however, business has been down. The psychics that the inertials should be protecting against have disappeared.

Things really kick off when a scout brings a young woman by Chip’s conapt one day to show off a new and profound ability. Typically an anti-precog will disrupt the seer’s ability by flooding their vision into the future with so many different potential futures that they don’t know which is real. Pat Conley, however, operates by directly altering past events, thereby creating a parallel timeline in which the present circumstances have been changed without anyone knowing they were ever any different. This superpower of almost limitless potential is one of Dick’s most creative excuses to write about tits.

“Under the blue, coarse blouse she wore nothing, and he perceived her breasts: hard and high, held well by the accurate muscles of her shoulders.

‘Are you sure you want to do that?’ he said. ‘Take off your clothes, I mean?’

Pat said, ‘You don’t remember.’

‘Remember what?’

‘My not taking off my clothes. In another present. You didn’t like that very well, so I eradicated that; hence this'" (31).

Perky or not, Chip, does not trust the girl. He rushes her to Runciter with a secret codemark on her paperwork meaning Do not hire. Regardless, both Joe and Pat find themselves admitted to a team of the organization’s top inertials for a high-paying job on the moon where it seems their arch rival has gathered all the missing psychics.

All of this, the missing psychics, the spy thriller intrigue, which takes roughly the first third of the book, turns out to be something of a misdirection, for the lunar job is a set-up, although we never exactly find out who is behind it. Was it Runciter’s rival, Ray Hollis, or Pat, or are the two in cahoots? Either way, the team is met with a bomb. Post-explosion is when things get all wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey, as the good doctor would say.

Before the bomb, things are a bit wacky; people dress in spider silk and spinner caps, sure, but the world pretty much makes sense. People behave naturally enough, given their environment. After the bomb appears, no one reacts naturally. There is practically no urgency in the lead-up to, or in the aftermath of, the explosion. It reads very much like a dream sequence, one of those nightmares where you can’t seem to run despite imminent danger, and the characters all speak in Wes Anderson deadpan:

“His rotund, colorful body bobbed about, twisting in a slow, transversal rotation so that now his feet, rather than his head, extended in Runciter’s direction.

‘I’ve heard of this,’ Runciter said to Joe. ‘It’s a self-destruct humanoid bomb. Help me get everybody out of here. They just now put it on auto; that’s why it floated upward.’

The bomb exploded” (67).

Runciter dies and Chip takes charge, leading the team off the moon and trying to get Runciter into cold-pac in time that his mind will remain preserved enough for half-life, alongside his wife, Ella, in a Swiss moratorium. The lack of urgency continues, however, and things just feel off. The survivors are allowed to flee without resistance, but they do so in no great hurry.

Runciter’s body, on the other hand, is decomposing at warp speed. Before they are able to get it back to the ship, it deteriorates beyond saving. At first, Chip and the gang blame it on the bomb blast. Radiation, maybe. Something had made them old. Not only those subjected to it, but also their material possessions. Packs of cigarettes that had been on site turn to dust at a touch.

But this theory falls apart when, back on Earth, far away from the lunar attack, freshly brewed coffee turns to mold and new cream curdles. It is as if everything around them has begun aging at an incredibly rapid speed. Before long, it begins to happen to living members of the inert A-Team: Wendy Wright is found mummified in Chip’s hotel closet the morning after she was meant to meet him there for some hokey-pokey.

After a time, things stop turning to dust and mold and instead begin reverting to earlier forms: Vehicles into older models, tvs into radios, until eventually the entire world of 1992 has retreated to 1939, with only Chip and the other inertials having any knowledge of the ~future~.

In his Exegesis, Dick expands on this vision of the universe, breaking it down like Shrek, with an onion analogy:

“the past is within things…the onion rings universe. Where is the past? Within what we see, at the hearts…Not behind but ‘below.’ Contained.

Well, if the past is within what we see (smaller concentric rings, constricted) perhaps one can reason that the future consists of larger rings than that which makes up our perceptual present… The next concentric ring of emanation would be the future... Which we reach toward, and which reciprocally reaches down to assist us.”

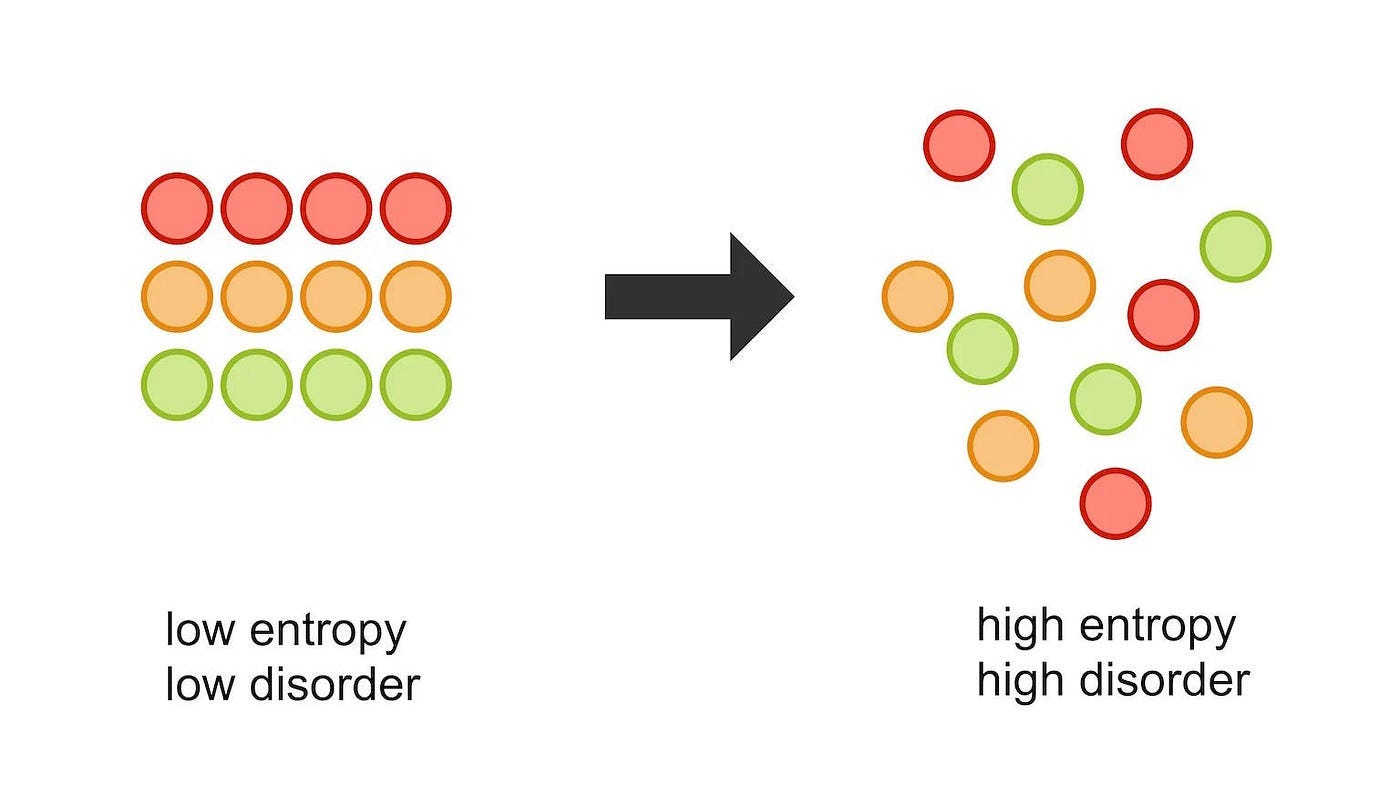

Not only does everything contain within it the past that led to its own creation, but there is some orgonic force continuously flowing outward, towards newer forms. Without that burning furnace of metabolism pushing outward, the form collapses in on itself, degrading into previous forms.

Now, were this to be a teleological universe, the outer onion rings would have to be out there in some pre-determined future, drawing the present forms towards themselves. This idea is represented in the text by the supposedly dead Runciter manifesting in strange ways, first as a face on a coin, then as a note in a cigarette carton, and finally as a voice on a telephone, spurring Pat1 to hypothesize:

“I see two processes at work…One, a process of deterioration…[the other] something to do with Runciter” (105).

And a page later:

“I think these processes are going in opposite directions. One is a going-away, so to speak. A going-out-of-existence. That’s process one. The second process is a coming-into-existence. But of something that’s never existed before” (106).

The Two Processes

About the time PKD was publishing Ubik, Henry Kissinger was cooking up his own project: Operation Menu, the secret carpet-bombing campaign that expanded the Vietnam War into Cambodia, killed hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of citizens, and played a large role in destabilizing the country and allowing for the rise of the brutal Khmer Rouge regime.

Back on the home front, college students opposed to the atrocities being carried out by their government held protests. On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard fired 67 rounds in 13 seconds into a crowd of these students on the Kent State campus, killing four and injuring nine. The shooters were initially charged, not with murder, but with depriving the students of their civil rights, for which they were later acquitted.

Present at the time was Jerry Casale, co-lead and bassist of the band DEVO, who personally knew two of the victims.

“All I can tell you is that it completely and utterly changed my life. I was a white hippie boy and then I saw exit wounds from M1 rifles out of the backs of two people I knew. I stopped being a hippie and I started to develop the idea of devolution. I got real, real pissed off.”

The band’s name, DEVO, is a shortening of Devolution which is the regression of humankind to a lower or worsened state. It was a response to the failed promise of progress promoted by politicians and the culture at large in the years after the second world war. Casale saw the process at work in the seventies and worsening today:

“It’s expanded way beyond our facile, smart-ass college guy concept. It’s real, and you can see it in the way that the planet’s burning up, but people have their heads in the sand about it like the proverbial ostrich. They’re not stepping up. They’re running away.”

The first of Pat’s two processes might be called one of devolution, of increased entropy and decreased stability. Although the novel is oft praised for capturing the uncertainty of reality, thereby giving the reader no solid ground on which to stand, readers in 2025 might feel right at home in the chaos. The cohesion of social life has drifted away and the lifeblood of our system is pooling in worrisome quantities. At times it feels as if society has lost its impetus and largely given up on any serious idea of the future. It’s cashing out time, baby. The lie of progress is up. Science, technology, and liberal democracy ain’t here to save us. It was all a goddamn marketing ploy. With this driving force bleeding out, we are being dragged downwards, not to some imaginary golden age of yore, but into an age of chaos, of plainclothes gestapo black bagging people on the street, fully broadcast genocide, and environmental oblivion.

Yes, the force of devolution in our world is about as obvious as spaceships turning into Model-Ts. But in Ubik, there is also that second process, that in-breaking voice intent on delivering a message of redemption, like the angel at the end of Fire Walk With Me. The latter half of the novel consists of Chip and the ever-dwindling gang slowly piecing together the fact that it was them who died and Runciter who survived, that they are now collectively in half-life, and Runciter is on the outside trying to get through to them, hence the coins and phone calls, and bathroom stall graffiti reading:

“JUMP IN THE URINAL AND STAND ON YOUR HEAD.

I’M THE ONE THAT’S ALIVE. YOU’RE ALL DEAD2” (120).

But if it’s Runciter behind the coming-into-existence, then what force is behind the devolution? There are continued arguments and theories on this topic, ranging from paranoia surrounding Pat’s abilities to proof of Plato’s Theory of Forms. In the end, it turns out to be the work of a kid named Jory, a character we briefly met in the second chapter as Runciter is visiting his wife, Ella, in half-life. During their meeting, Ella’s presence weakens and is eventually replaced by the neighboring conscience.

Runciter complains to the moratorium’s manager who explains that this can happen after prolonged proximity. Especially when one conscience’s cephalic activity is stronger than its neighbor’s. In another instance of how sleazy a world we are in, the manager offers to move her into isolation and protect her body with Teflon, for a fee, of course. Runciter agrees to pay it, but he is warned it may be too late. Jory may have permeated her permanently.

Despite this rather major mishap, it is to the same Swiss moratorium that Runciter delivers his deceased employees, and into the hands of Jory who has grown powerful enough to generate the world the half-lifers have been occupying since the explosion.

“Wherever you and the others of the group went, I constructed a tangible reality corresponding to their minimal expectations. When you flew here from New York I created hundreds of miles of countryside, town after town—I found that very exhausting” (198).

To sustain his creation, Jory must consume the psychic presence of the other half-lifers. We are given to believe that he has been doing this for years by the time Chip and the gang arrive, and in this way he has grown so powerful that he emits this demiurgic control of the half-life world at large, not only generating the space the inertials have been moving through, but filling it with NPCs. The only real entities they have come into contact with have been one another and the manifestations of Runciter who is trying to reach them from beyond, but for all his powers even Jory cannot keep the world from regressing.

“Jory had…constructed…the world…of their own time. Decomposition back to these forms was not of his doing; they happened despite his efforts. These are natural atavisms, Joe realized, happening mechanically as Jory’s strength wanes. As the boy says, it’s an enormous effort. This is perhaps the first time he has created a world this diverse, for so many people at once. It isn’t usual for so many half-lifers to be interwired” (201).

Jory explains all this to Joe Chip, the last surviving member of the gang, as he begins to consume his lifeforce. Joe grows increasingly weary and wants nothing more than to find somewhere to lie down and let it happen, but Runciter manages to deliver him messages, urging him to reach his hotel room, which he just manages to do, climbing flights of stairs as Jory taunts him. Once there, he finds a can of Ubik, a miraculous spray that is able to stave off Jory’s constant draining. He douses himself with its contents and is instantly rejuvenated.

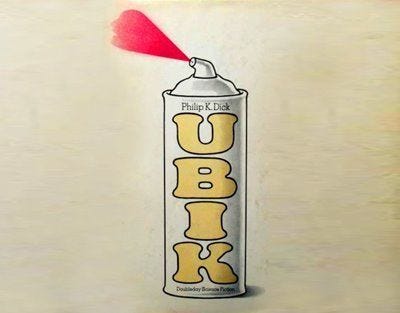

Ubik

While the product only materializes in a usable form in the final pages of the novel, its presence haunts the book, providing not only the title, but epitaphs before each chapter in which Dick uses copywriting language to advertise Ubik in a range of different ways: as if it’s a used car, a light beer, a cleaning/beauty product, etc. He seems to be playing with that unbridgeable gulf between the commodity-as-advertised and the commodity-as-object, but Ubik is that miraculous substance that actually fulfills the promise.

With the final epitaph, Dick drops the advertising language and takes on the tone of a holy text, equating Ubik more to something like the Tao, or Logos:

“I am Ubik. Before the universe was, I am. I made the suns. I made the worlds. I created the lives and the places they inhabit; I move them here. I put them there. They go as I say, they do as I tell them. I am the word and my name is never spoken, the name which no one knows. I am called Ubik, but that is not my name. I am. I shall always be” (215).

By the time Dick began writing his Exegesis in 1974, Ubik had come to mean quite a bit more to him than a macguffin in one of his novels. In the Works Index, it is cited across 169 different pages, or roughly 20% of the doorstop collection, which is more often than any of his other novels.

Dick came to believe that he was, at most, co-writing his own works. That they were being beamed to him from some place in the future in order to help guide the world towards redemption. For Dick, Ubik was this guiding force. In a postscript to a letter written to Peter Fitting, he writes:

“In terms of Ubik (not the novel but the force described in my novel) perhaps I was already becoming aware of this total coherence which the universe is moving toward and which bombards us backwards…with information about itself, thus giving us a certain awareness of itself…Ubik talks to us from the future, from the end state to which everything is moving; thus Ubik is not here - which is to say now - but will be, and what we get is information about and from Ubik, as we receive TV or radio signals from transmitters located in other spaces in this time continuum” (10).

Hymn of the Soul

Erik Davis, writing in his brilliant study of Dick in High Weirdness, highlights an ancient Near Eastern story called the Hymn of the Soul that PKD became enthused with while writing his Exegesis. The Hymn, contained in the Acts of Thomas, concerns the story of a boy, a son of the king of kings, who is disguised and sent to Egypt in order retrieve a pearl from a serpent or dragon. However, as if in Fairyland, the boy eats of the food and forgets his quest, his origin, and his identity. He forgets that he is a king’s son, and becomes a slave to the king of Egypt.

Hearing of their son’s waywardness, the boy’s parents send him a letter. When the hero reads the letter, he recalls his true home and true identity, and gains the capacity to complete the task. He returns home where he once again dawns his heavenly garment.

“Though Dick was not drawing these connections at the time he wrote Ubik, in the wake of 2-3-74, he was quick to notice the similarities” (349), Davis writes, comparing this letter from home to Runciter’s in-breaking messages; both are examples of how “the transmundane penetrates the enclosure of the world and makes itself heard therein as a call” (348).

Indeed, the idea of the initiating text is key to Dick’s way of thinking. In the Hymn, the letter from home acts as the source of anamnesis, or unforgetting. In his own life, Dick conceived of Ubik as an outside force sending messages backwards through time, meant to guide humanity towards a fixed/redeemed point in the future. In the novel, Runciter’s messages are meant to awaken the dead to their situation. In all three cases, these messages, once received, still must be acted upon. The hero must face the serpent; Dick must perform the work of writing; and, in the novel, Ubik must be created by those living within their fallen world as a means to heal themselves.

Though we find ourselves far from our heavenly home, living in a system that feasts on our very humanity in order to persist, we must each of us remember our origins, and in the briefly burning furnace of our metabolism, against the ravishing of devolution, we must each of us build our own soul if we hope to survive the chaos abounding.

As Ella says, The battle has to be fought on our side of the glass.

Wait, why’s she hypothesizing? Isn’t she a bad guy. Actually, no. Well, maybe. Either way, we’re moving on. Try to keep up.

You’d think this one would be pretty clear.

Great essay revisiting one of my favorite novels, but one always shrouded in so much complexity and ... hyperreality? Something like that. I'd never heard of the Devo-Kent State connection, Davis's Hymn of the Soul comparison, or that Stanislaw Lem essay, which I'll have to go back to. The reverting forms of backwards-moving times has simmered in my mind for a long time. I started to think of this from a lens of evolutionary biology, I wonder if anyone's written more about that? I'm not sure where telos fits in from that perspective, but life often grows towards something while moving through stages, and generations, too, like the generations it takes to build a civil society or culture. Objects like the spaceship, the car, carriages, they're extensions of human life like tools of any animal, like beaver dams or nests. There's something permanent and immutable about the "form" to the human species. This gets interesting with things like computers, and pets. Anyway, great to feel transported back into Ubik. Wes Anderson should adapt a PKD novel, he needs some new more challenging source material.

Ubik is one of my all-time favorite books.

It pairs well with The Lathe of Heaven by PKD’s close contemporary Ursula K. LeGuin. I feel that those two books are getting at the same idea from different perspectives.