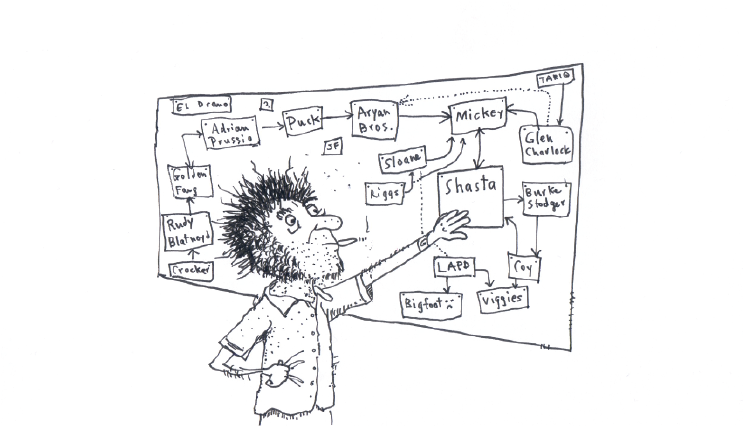

Ultimately, everything really is connected, man. And that’s all well and good. A profound conclusion to arrive at, but not necessarily the answer you want your private eye to deliver or else your results are not only going to be so overwhelming as to be meaningless, but the amount you’re going to have to fork over just to cover all the red string will be astronomical.

(Under the red string, the cork board.)

That is, unless your private eye is willing to work on spec, like Doc Sportello, the perma-stoned hero of Thomas Pynchon’s seventh novel, Inherent Vice, who ends up taking on at least five cases throughout the course of the novel, whether via recruitment or self-assignment, with no guarantee of a paycheck.

Doc lives in Gordita Beach, a fictional LA satellite town based on Pynchon’s old stomping grounds, Manhattan Beach. The word ‘suburb’ summons the wrong image. Not only is the beach town said to be built right on top of a “sacred [portal] of access to the spirit world” (355), but it is a cheap haven for surfers and hippies, or at least it had been, but that all seems to be coming to an end, here in the year 1970. The specter of gentrification haunts the novel1. And not only gentrification in its usual sense, but also a sort of gentrification of the collective soul.

It’s a common theme running throughout Pynchon, and one we have referred to before somewhat vaguely as open windows in history. These windows are cultural epochs in which it seems like stodgy old history might come off its tracks and proceed in some totally new direction; when the artificiality of our world, the single bleating fact that It Does Not Have to Be This Way, becomes a powerful, counter-cultural mantra; or, as the man himself, Michael S. Judge puts it, these are times—

"when another world seems not just possible, but about to emerge from this one. When…you could stand against the day or just a few inches to the side of the day and everything you had been taught, all protocol of daylight and public behavior with which you had been inculcated, it all shifted off its axis just a little bit, and through the crack between that and the edge of the frame you were able to perceive a world which, though ostensibly and outwardly identical with the world you knew, was so charged with the possibility for transformation, with a whole alchemical index of dormant changes, that you could never return to the officially installed public daylight as quite the same person.”

These are the periods Pynchon most likes to use as the setting for his novels: the revolutionary ferment in colonial America in Mason & Dixon, the turn of the century labor unrest in Against the Day, the promise of the internet and the new millennium in Bleeding Edge, but it is the American 1960s that he returns to most often: whether mapping them onto postwar Europe in Gravity’s Rainbow, dropping directly into them both here2 and in The Crying of Lot 49, or lamenting their failures in Vineland.

For every open window, there is a hand to reach out of the dark and slam it shut. Counter-balancing these dreams of new worlds are their violent foreclosures, or what Michael Judge calls Reconquest. This on-going American Reconquista is carried out by the forces Pynchon most succinctly refers to as They, though in Inherent Vice They take on the guise of a sprawling, shadowy cartel known as The Golden Fang.

On the Case

As with so many great noirs, it is a real estate scandal that composes the vortex at the center of this whirlpool of a novel. Doc is dragged into its pull by the reappearance of his ex-old lady, Shasta Fay Hepworth, who lets herself into the Sportello abode one fine California evening. Tailing behind her is a shadow of foreboding and paranoia that will saturate the rest of the novel. Though often remaining just off screen or out of focus, this shadow is not only a stylistic nod to a genre Pynchon is pastiching, but a telltale sign of the impressionist universe that all noir inhabits.

It’s a foreboding time, after all. The ~sixties~ may be limping on, but the idea that they might actually birth a new world is faltering. The war in Indochina rages on. Fred Hampton is dead. The Kennedy brothers are dead. MLK is dead. The Manson Trials are on. The so-called counter culture is rife with informants, so that no one can fully trust anyone. And Shasta has gone and gotten herself tangled up with some powerful people. Afraid she might be being surveilled, and with no one else to turn to, she asks Doc for help locating her new boo, a real estate tycoon by the name of Mickey Wolfmann, who has gone missing after having a change of heart and deciding to give his considerable fortune back by building a desert utopia called Arrepentimiento, or Sorry About That.

It never gets much past the planning stage, but it was to be a place “anybody could go live…for free, didn’t matter who you were, show up and if there’s a unit open it’s yours, overnight, forever, et cetera et cetera” (248).

Somewhat reluctantly, Doc agrees to look into it, which makes for Case #1.

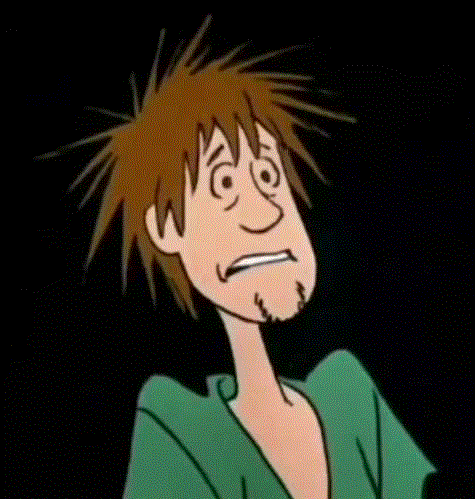

As we here at Gnostic Pulp have warned in the past, an investigation is ripe territory for Trickster. If one is not careful, the gumshoe can quickly find themselves on a wild goose chase. And Doc, he ain’t exactly the careful type. If he were a part of the Mystery Gang, he’d most certainly be Shaggy, into whose cadence Pynchon, like, totally dips throughout this text, man.

Case # 2 arrives in the Sportello office the next day. A man named Tariq Khalil is owed money by a member of the Aryan Brotherhood, Glen Charlock, with whom he did business in prison. Just so happens, get that red string ready, boys, Charlock is now a bodyguard for none other than Mickey Wolfmann. Coincidentally, one of Mr. Wolfmann’s past developments has eaten Tariq’s former home. After getting out of Chino, he goes looking for his former street gang, and finds not only them missing, but the turf itself.

“Not there. Grindit up into li’l pieces. Seagulls all picking at it…Nobody and nothing. Ghost town. Except for this big sign, ‘Coming Soon on This Site,’ houses for peckerwood prices, shopping mall, some shit” (16-17).

Tariq calls this an act of malicious gentrification, revenge for the Watts Insurrection. The so-called riots were a public response to a case of police brutality, not dissimilar to the George Floyd Uprising of 2020.

In a recent Chapo episode, Felix Biederman suggested the Democrats’ continued refusal to do anything to stop the ongoing genocide in Palestine, despite large and frequent demonstrations by their base, is in some ways connected to their reaction in 2020 when Pelosi and others democratic lawmakers were embarrassed into kneeling in the capitol, wearing Kente stoles.

“Never again will they allow the demonstrators in the street to be the arbiters of justice.”

Demonstrations against the genocide in Gaza are carried out by people who believe in a world in which America is no longer inherently a genocidal colonial project3. Likewise, both the Watts and George Floyd uprisings were explosions of It Does Not Have to Be This Way by a public that could plainly see the artificiality of the conditions they have been forced into: living as second class citizens in their own homes. Both the police abuse of Marquette Frye and the murder of George Floyd, are tragically common events4, but in the right conditions their indignity cannot be tolerated and they act as the igniting acts to rebellion, and for a brief moment it seems the old world actually can burn, and something new replace it.

But, as Pynchon’s thesis states, the idea that the world not only could, but should be different, must be violently stamped out. In Watts, fourteen thousand members of the national guard were brought in to do the stomping, and they had quite the effect. As Pynchon himself covered way back in ‘66, even the police murder of a Watts’ man who ran a red light while racing his pregnant wife to the hospital only a year after the uprising did not set off the same response. As he quotes one community preacher, “Make any big trouble, baby, The Man just going to come back in and shoot you, like last time.”

But that suppressed response simmers in the background throughout Inherent Vice, as does the boot ready to clamp it down. This is the threatening atmosphere against which many of the wacky sixties antics throughout the book are back lit, and its presence is what separates this work from so much nostalgia-peddling that goes on in the endless packaging and re-packaging of the sixties which function to bury any kernel of actual revolution that might have once existed beneath so many layers of mediated imagineering it would be impossible to excavate.

Under such threatening circumstances, it is no surprise that when Shasta ends up missing, Doc can’t help but assume the worst5, and bringing her back safely becomes, if not exactly, Case #3, then at least a prayer that never fully leaves his lips.

Case #4 is a more official one. A supposed widow, Hope Harlingen, hires Doc to look into the death of her estranged husband, which she has reason to find suspicious. And Case #5 is one he is pushed into by his cop frenemy, man by the name of Bigfoot Bjornsen, whose partner was killed in what he believes was an inside job carried out by the LAPD itself.

But as we hinted in the beginning, all these cases meet, or seem to meet, in a hub upon the cork board labeled The Golden Fang.

The Golden Fang

Stand on the beach and gaze into the surf in hope of witnessing the return of the sunken continent of Lemuria6, and you’re more likely get a glimpse of the sun gleaming off the heroin-running schooner named The Golden Fang. These are the two worlds at war with one another: the dreamt of new one and the occulted enforcer that maintains this one.

The Golden Fang is not only the name of a boat that is said to be used to smuggle counterfeit currency, heroin from Indochina, and guns to Cuba and other Latin American countries, both of which reek of CIA activity, a la Gary Webb’s Dark Alliance, but it is also the name of a tax haven used by a syndicate of honky dentists, an alliance between organized crime and intelligence, a vampiric method of execution, and the Greek translation of an asylum (Chryskylodon) that is meant to help addicts get clean, often at the cost of turning snitch.

The Golden Fang in its boatly manifestation is a schooner which Doc learns was once named Preserved and had been the property of a blacklisted actor named Burke Stodger, who fled the country in it after being chased out of Hollywood for his communist sympathies.

Only a couple years later, both he and his ride reappear, “as if by occult forces…refitted stem to stern, including the removal of any traces of soul” (93).

Zombies form a motif in the novel, and not only the tequila ones sucked down by Doc and his lawyer, but the actual undead seem to be lurking everywhere. Stodger is a great example. He sold out not only everything he believed in, but the names of others who shared similar beliefs, so as to be allowed to return to the movies and hang out in the golf course clubhouses. Even then, the only roles he can get are “in modestly budgeted FBI dramas like I Was a Red Dope Fiend and Squeal, Pinko, Squeal!” (309).

The boat is forced to suffer a similar fate:

“At the time of her reappearance in the Caribbean, for example, she was on some spy mission against Fidel Castro, who by that point was active up in the mountains of Cuba. Later…she was to prove of use to anti-Communist projects in Guatemala, West Africa, Indonesia, and other places whose names were blanked out. She often took on as cargo abducted local ‘troublemakers,’ who were never seen again. The phrase ‘deep interrogation’ kept coming up. She ran CIA heroin from the Golden Triangle. She monitored radio traffic off unfriendly coastlines and forwarded it to agencies in Washington, D.C. She brought weapons in to anti-Communist guerrillas, including those at the ill-fated Bay of Pigs” (95).

The boat and her former owner have become further victims of the American Reconquest. Not only have they been neutralized, but they’ve been made into their opposites, reconfigured into assets for the other side. This is how Reconquest works. It is the same with the hippies’ drugs, those same portals that were meant to free the mind, are being sold to them by Golden Fang-backed fronts. Not only that, but once they are properly addicted, it is a Golden Fang-backed asylum that will help you kick the habit. They get you coming and going, and as you’re going they might tap you on the shoulder, pull you into a side room, offer you a measly paycheck in return for a bit of information; Nothing crazy, mind you. You will be allowed to live your normal life, as long as you continue to supply us with names, that is.

This is the situation Doc finds Coy Harlingen, subject of Case #4, entangled in. In an attempt to kick his heroin addiction, he’d been manipulated into faking his death and doing work for a range of Golden Fang-affiliated forces.

Poor Coy, he’s but a simple surf rock saxophonist. What chance does he have against such a cartel when even Mickey Wolfmann is struck down for going against their interests?

Wolfmann is evidence that no individual, no matter how powerful, can go against the day. In our syndicate reality, the individual simply plays a part. This is true not only of the masses, but also those individuals who make up The Golden Fang itself. It is a self-perpetuating logic that can select and replace the parts it needs. Like God, it is a circle whose center is everywhere and circumference is nowhere.

Under the Mask, the…

This is the mystery Doc is asked to wade into. No wonder no solid shapes ever coalesce. With this many moving parts, it is nigh on impossible to say what, exactly, The Golden Fang is. Like V in Pynchon’s first novel, it is a floating signifier. It refers to something different depending on who is speaking.

Thomas Jones, in his review in the London Review of Books, simplifies the cartel by calling it capitalism itself. Dr. Gregory Marks, in his typically brilliant Wasted World analysis, makes reference to a whole range of academic readings that we here at Gnostic Pulp do not have access to, but which variously liken The Golden Fang to a multinational corporation, the changing focus of American imperial interest, and to a “historical anxiety in its function as an interstitial figure between the era of Fordism and its neoliberal successor”.

Marks himself draws out the theme of fossil capital, adding the face of oil to The Golden Fang’s repertoire, and it fits quite well. The struggle for the control of petroleum has acted as a main driver of the second half of the twentieth century, and through today. Although it is rarely given as an official reason for any conflict, it is pretty much an open secret. Perhaps a limited hangout, in a way. A bluffed lapse that offers a glimpse behind the facade, so as to better hide the rest of what’s going on back there.

Say the Mystery Gang ever did somehow get a drop on The Golden Fang. What face would be revealed beneath the mask? Probably something like the biblically accurate angel meme, and those meddling kids would lose their minds in a Lovecraftian fit of madness.

The Golden Fang cannot be seen directly. It is what is sometimes referred to as The Deep State, the functions of capitalism that must be carried out in order for the system to operate, but which cannot be performed in daylight. For that reason, it is legion. It is dispersed. There is no underground lair in which the ultimate mastermind of The Golden Fang carries out his whims. It is a loose confederation held together by the logic of capitalism itself.

Trying to solve this complex of cases delivers Doc into a vast fog. This is the condition all those who dare peer through the open window pay witness. There is no new world waiting on the other side, for any new world will have to be constructed. There is a blank expanse. Those who venture into it have nothing but one another, like cars moving in a caravan to navigate the hushed whiteness of a dense fog.

“He crept along till he finally found another car to settle in behind. After a while in his rearview mirror he saw somebody else fall in behind him. He was in a convoy of unknown size, each car keeping the one ahead in taillight range, like a caravan in a desert of perception, gathered awhile for safety in getting across a patch of blindness” (368).

As he drives, Doc longs for the fog to burn away and to find himself magically transported to a new world; for Lemuria to have risen from the ocean and pushed aside old, rotten LA, but even if it did, he has to admit, people might not notice. That old idea that It Does Not Have to Be This Way has been stamped out of us so many times, and the artificial reality we live in has been sutured to the surface at such cost that it is exceedingly difficult to see beyond its edges.

“People in this town saw only what they’d all agreed to see, they believed what was on the tube or in the morning papers half of them read while they were driving to work on the freeway, and it was all their dream about being wised up, about the truth setting them free. What good would Lemuria do them?” (315).

It is important that Inherent Vice takes place in Los Angeles, for that is one of the focal points of this reality’s production. Hollywood endlessly re-contextualizes everything. For those who did not live through it, what better way to experience a past era than via film? And when The Golden Fang has its influence upon Hollywood, it’s like Orwell said:

“The mutability of the past is the central tenet of Ingsoc. Past events, it is argued, have no objective existence, but survive only in written records and in human memories. The past is whatever the records and the memories agree upon. And since the Party is in full control of all records, and in equally full control of the minds of its members, it follows that the past is whatever the Party chooses to make it. It also follows that though the past is alterable, it never has been altered in any specific instance. For when it has been recreated in whatever shape is needed at the moment, then this new version is the past, and no different past can ever have existed. This holds good even when, as often happens, the same event has to be altered out of recognition several times in the course of a year. At all times the Party is in possession of absolute truth, and clearly the absolute can never have been different from what it is now.”

Replace the Party with The Golden Fang, and bing-bam-boom.

The very structures Doc and his fog-bound caravan move through and within belong to Them, to The Golden Fang. The Santa Monica Freeway. The cars. The gas they are burning. It may all be a production, but it is a production for which no expense has been spared.

The sixties were and continue to be so violently foreclosed upon because that was the last time a window capable of threatening the production truly opened within the imperial core. What followed was the last great reset of American society, and everyone has been playing the roles they were cast into since then. The Democrats became nominally the party of justice and social welfare while the Republicans became the party of old-fashioned values and laissez faire capitalism. Some appeasements were handed out to a select portion of the population via the New Deal, and we all moved on, grew up, called it Progress.

But now, some sixty years on, the appeasements have dried up, and the contradictions inherent to this system are squealing too loudly to ignore. The Republicans are doubling down, embracing austerity and fascism, and rather than veering the other way, the Democrats are also moving further right, riding the Republicans’ wake, at about a decade remove. Their bases are meant to follow loyally behind them, but there is so much being papered over that it is proving a challenge, both on the home front, in the form of ICE, the return of the Epstein case, and plainly open corruption, and abroad as the genocide in Palestine.

Trying to accept the official narrative is breaking people’s brains. The production is faltering. A new reset is glaringly necessary.

If there is a window opening once again, it was not lifted by any struggle here, but rather thrown open in Gaza, in one of those pockets of bitter reality where historically less discretion can be used in slamming it shut.

If there ever does come an ultimate rupture, it is not likely to occur in Gordita Beach, amongst the hippies or their equivalents, but rather in one of these places where the sutures holding together the whole apparatus are stapled violently into the Earth at the price of the people living there, where the cruelty is unbearable, and there is no way to carry on living except with the knowledge that It Does Not Have to Be This Way.

[Exit Music]

“Long, sad history of L.A. land use…Mexican families bounced out of Chavez Ravine to build Dodger Stadium, American Indians swept out of Bunker Hill for the Music Center, Tariq’s neighborhood bulldozed aside for Channel View Estates” (17).

Okay, so technically it is 1970 in Inherent Vice, but the cultural epoch known as the sixties, like many of its denizens, dragged its feet and showed up a little late and then overstayed its welcome, so that they bleed over a bit into the next decade.

“yet there is no avoiding time, the sea of time, the sea of memory and forgetfulness, the years of promise, gone and unrecoverable, of the land almost allowed to claim its better destiny, only to have the claim jumped by evildoers known all too well, and taken instead and held hostage to the future we must live in now forever. May we trust that this blessed ship is bound for some better shore, some undrowned Lemuria, risen and redeemed, where the American fate, mercifully, failed to transpire.”

“how very often the cop does approach you with his revolver ready, so that nothing he does with it can then really be accidental; of how, especially, at night, everything can suddenly reduce to a matter of reflexes: your life trembling in the crook of a cop's finger because it is dark, and Watts, and the history of this place and these times makes it impossible for the cop to come on any different, or for you to hate him any less. Both of you are caught in something neither of you wants, and yet night after night, with casualities or without, these traditional scenes continue to be played out all over the south-central part of this city.”

“Ah, fuck no. Not this” (34).

“and what better time than now,” as Doc’s ex-secretary, Sortilège, points out, “with Neptune moving at last out of the Scorpio death-trip, a water sign by the way, and rising into the Sagittarian light of the higher mind?” (102))

great work on this one dude

What a tour! Though born in the late seventies in India, I carry with me a whiff of a different possibility - maybe similar to what was in the sixties.. one that was mostly gone till I read this.