We Are Pynchon's Fail Sons and Thot Daughters

on Thomas Pynchon's "Vineland"

"Take care of your dead, or they'll take care of you."

There’s a certain lack of seriousness to American life. This feeling that it’s not quite real, that it is happening somewhere else, on a higher level, to which we are only witnesses. Life is what we see on the tube, on the internet, up on Mt. Olympus. That much is evident in our rampant celebrity worship. What we do from day to day is meaningless groveling. We wake up, we go to work, we squirm about in our little fleshy bodies with all their fleshy little problems. We go out to eat, we go to the colon and rectal doctor and sit in the waiting room, we waste away at our miserable jobs, and we stay glued to our phones because they are our windows into the glowing world of Real Life. We are lucky, really, to even get that glimpse. Can you imagine living without access to Life?

This uneasy feeling is a result of an imbalance. We are unplugged from the eternal. We have cleaved our ties to the past and our responsibility to the future, and elected to reside in a sort of Year Zero, a place without past or future, or to borrow a phrase from Jacob Foster, J.F. Martel, and Phil Ford, in their essay: Care of the Dead: Ancestors, Traditions, & the Life of Cultures, an eternal presentism

“Such an outlook makes the past appear something like a faded black-and-white film that, though it clearly refers to reality, plays no active part in it.”

But it’s not only the past that takes on this effect. The future does not seem real either. We are constantly told of global catastrophes just over the horizon, but they never seem to quite reach us, at least not in the way we imagined they would. Even the present becomes ephemeral, as we covered above.

In a healthy society, The Dead, The Unborn, and The Living form a tripart alliance by which meaning is embedded within existence. The Dead are not simply gone. Far from history’s waste matter, they form the very structure in which we exist. From the beginning, the teeming hoards pouring forth from the sea have given their bodies to enrich the soil, creating an earth upon which life could take hold. The Dead have gone before us and created the context in which we live: physically, linguistically, socially, and genetically.

The Unborn, which can be expanded to all those who cannot speak for themselves, such as non-human animals, ecosystems, etc., when seen as equals, give The Living meaning beyond their own existence which so easily might otherwise descend into nihilism, hedonistic pleasure-seeking, and self-enrichment. Their promise expands the scope of time and deflates the dangers of egoism by providing a sense of responsibility for the future, a greater purpose, a destiny.

It is a delicate union and there is danger in any one side claiming dominion over the others. Where The Dead govern, necrocracy rules. Tradition becomes suffocating and society stagnates. Were The Unborn to claim the throne, The Living would become resentful servants of the future and the central impetus of the whole system would dim. But when The Living take charge, they deny their counterparts’ very existence; the past is forgotten and the future misprized causing life to become hollow, disconnected, and listless. That sneaking feeling of irreality sets in. Nihilistic self-enrichment and pleasure-seeking become the only pursuits imaginable. There is no fellow feeling, no ties that bind, and no incentive to preserve anything for the future. Just get while the gettin’s good.

In such a situation, The Dead and The Unborn can make their presence known only through hauntings and possessions.

We live thus haunted and possessed.

Reagan’s Time War

Vineland, Thomas Pynchon’s long-awaited follow up to Gravity’s Rainbow, came in the form of a comparatively simple tale of a single family unit and its messy history1. In the novel’s present day of 1984, Zoyd Wheeler, aging hippie and single parent, is scraping by on disability checks and odd jobs while raising his teenaged daughter, Prairie, until they are (literally) invaded by the past in the form of rogue federal agent Brock Vond, who has had a decades-long obsession with Zoyd’s ex-wife/Prairie's absentee mother, Frenesi. It seems Vond plans to kidnap Prairie in order to flush Frenesi out of her long hiding.

Thus kicks off the novel’s main thrust, which follows Prairie’s flight from Vineland during which she falls in with D.L., her mother’s ex-best friend, and her partner, Takeshi Fumimota. Over the course of the novel’s 380-odd pages, Frenesi’s complex karmic entanglements are slowly revealed, through film, recall, and flashback.

Pynchon excels at situating his works in history, and here he examines the reign of presentism, or the oligarchy of The Living, through the rise of neoliberalism. The doors to the underworld have been plugged and lost. The future has been waylaid and will now be dictated by the present. Another common theme in Pynchon is that of closing the open, cutting up flows into lines and pieces. Here that is happening not only with California real estate encroaching upon the final remnants of redwood forest in the far west, but even the wild vines of possible futures are being dutifully pruned and trained along a particular trellis by sober and determined gardeners.

This is Reagan’s Time War. Not only is Reagan (and here we are using Reagan as shorthand for the class he represents) determined to erase all ties of responsibility to the future by eliminating any funding that allows for a stable society to exist, but he also is dead set on scrubbing out the past, and rewriting it in his own way, using media as one of his prime weapons. Throughout the novel, characters are constantly watching the ‘tube’, including a slew of hilarious inventions, such as the Young Kissinger biopic, dir. by Woody Allen, and the Robert Musil Story staring Pee Wee Herman.

These films rewrite popular history in sneaky ways. Unlike in dystopian works such as Orwell’s 19842, it is not always the state directly reworking history (although they might here be funding it). With the rise of film and television, the tools of control can be Trojan Horsed in through our entertainment. A little sugar helps the medicine go down, after all. And what can’t get a fictionalized reboot can just be memory-holed, tossed into the abyss of severed time while our eyes are glued to the tube:

“‘They can’t take what happened, what we found out.’

‘Easy. They just let us forget. Give us too much to process, fill up every minute, keep us distracted, it’s what the Tube is for, and though it kills me to say it, it’s what rock and roll is becoming—just another way to claim our attention, so that beautiful certainty we had starts to fade’” (314).

All of which is bad news for us because “the human machine functions according to the determined programme ‘maximum pleasure at minimum cost’” (350), or so the anonymous author of Meditations on the Tarot writes in his chapter on Death. It was on a hunch that I turned to this book which just might be the most powerful reference in my humble library. I think of it almost as a living thing. Anytime I have been compelled to consult this text, it has supplied an answer that has been both unexpected and eerily synchronous.

Here, the author goes on to further clarify, writing that it “is only functioning of the human machine when a rich man declares himself anti-communist” (350) and vice-versa because their material conditions benefit from such stances. “But it is a miracle—that is to say an act of freedom— when a rich man abandons his possessions and embraces poverty” (350).

Every human action can be thus separated: miracle or function. Function is the base reaction of the human machine. It happens practically automatically, without need for self-reflection or critical thinking. The miraculous, then, is that which does not just happen; it has to be performed.

“One only does miracles, and all that is done is a miracle, and nothing is done without it being a miracle” (350).

What we are confronted with in Vineland, then, is a world that is the result of a perverted miracle. It’s 1984, and rather than the rich abandoning their positions to fight for communism, the nefarious They have turned the impoverished against themselves and duped them into embracing a system which only exploits. This trick is not one pulled off easily, but over many years and at incredible expense. It works best on a citizenry that has been plucked out of time, removed from the flow of its past struggles, and given little reason to invest in its own future, all of which is part of Reagan’s program.

This dark miracle is nothing less than the installation of a new lifeworld, the successful replacement of the way we, The Living, understand and experience the world. The old metaphor of an organic and timeless, even, perhaps, divine, network has been switched out for its digital counterpart, a program that imitates life, and a vision of the universe that robs meaning from both The Living and The Dead.

“If patterns of ones and zeros were ‘like’ patterns of human lives and deaths, if everything about an individual could be represented in a computer record by a long string of ones and zeros, then what kind of creature would be represented by a long string of lives and deaths? It would have to be up one level at least —an angel, a minor god, something in a UFO. It would take eight human lives and deaths just to form one character in this being’s name — its complete dossier might take up a considerable piece of the history of the world. We are digits in God’s computer…and the only thing we’re good for, to be dead or to be living, is the only thing He sees. What we cry, what we contend for, in our world of toil and blood, it all lies beneath the notice of the hacker we call God” (90-91).

The sense of meaning once embedded in human existence is totally absent in this vision of the universe in binary code. This situation forms the backdrop of Vineland. People become numbers. Frenesi, who had been living in a federally funded witness protection program for years, marvels at the ease with which she is cleared out of the system. Her funding is wiped without warning, as easily as pushing a button, and without care for the results “because in this country nobody in power gives a shit about any human life but their own” (229).

And if no one cares for The Living, then what hope is there for The Dead?

Care for The Dead

Vineland’s dead are both metaphorical—the dream of the sixties as remembered in the meat locker of the eighties—and the actual dead, or would-be dead, but they can’t quite move on. Thanatoids3 are undead spirits who inhabit the literal ghost town of Shade Creek lost back in the redwoods. They are trapped in a kind of purgatory, tied up by karmic blockages4, victims of “unanswered blows [and] unredeemed suffering” (173). They spend most of their time watching television. In fact, one even says there could never be a show about thanatoids because all the thanatoid characters would do is watch tv.

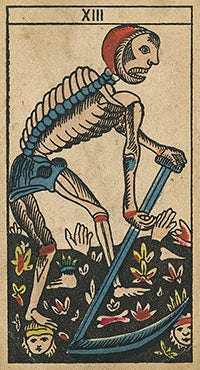

Death’s scythe should severe these ties, so that these restless spirits can be truly dead, but, remember, true Death is being denied in this Eternal Year Zero of Presentism. True Death does not mean absence, but rest, as in a stone surface must be at rest before it can be used as a foundation, but the ground is not only a foundation. The surface is also a seedbed out of which are born The Living, as is seen on the thirteenth Arcanum of the Tarot, Death: new life sprouts from a field made fertile by The Dead5.

In the Meditations chapter on Death, the author spends some time fleshing out the story of Eden. The serpent, like God, promises freedom from death, but this freedom is akin to neoliberalism’s repression of the past and the future rather than any promise of eternity. It is the puffed up ego of the Individual, life colonizing the furthest horizons, but lacking any depth. Only the Divine deals in verticality. While the author of Meditations is a Christian hermeticist, we can take that Divinity metaphorically and read it as Humanity Redeemed, the tripart allegiance restored. In this way, The Dead are not simply extinguished, but they stay with us and provide the scaffolding of our world.

In the Care of the Dead essay, this idea is sketched out through the example of music:

“In artistic practice, the dead are vividly present in our very bodies. When a cellist plays a Boccherini sonata, the shapes and gestures of long-dead hands are revivified in her own.”

Indeed, every time we speak, we are using the language of The Dead. We live in their world. How might we, the future Dead, be better stewards, for the future Living, who are really ourselves? In their essay, Phil Ford suggests the Buddhist practice of keeping an altar featuring pictures of the familial dead who can stand in for all The Dead, and anytime the living gather for no matter how insignificant an event, lighting a piece of incense and inviting them to join.

If that’s too woo woo for ya, the anonymous author of Meditations gives us another way of interfacing with The Dead: Recall, of which there are four types:

Mechanical Memory is the lowest type of recall. It is related to function as it is what is saved automatically. It is unreliable and easily corrupted by false implants, such as interferences from the tube, propaganda, or simply degradation over time. This base type is eventually supplemented by Intellectual Memory. Intellectual Memory fortifies Mechanical Memory by filling in the gaps with rationality and intellect. This, too, is vulnerable because it can be easily swayed by rational (or rational-sounding) rhetoric and reason. Without a moral standing, reason is a dangerous tool. That is why Moral Memory, the third tier, is indispensable, for it allows one to see and connect beyond oneself. It strengthens one’s beliefs through ideology and provides a robust bullshit filter.

Then there is Vertical or Revelatory Memory which is basically anamnesis, or a gnostic unforgetting:

“It is a ‘memory’ which does not link the present to the past on the plane of the physical, psychic and intellectual life, but which links the plane of ordinary consciousness to planes or states of consciousness higher than that of ordinary consciousness…It is the link between the ‘higher eye’ and the ‘lower eye’, which renders us authentically religious and wise, and immune to the assaults of skepticism, materialism and determinism…It is also…the source of certainty…in immortality” (346).

Not immortality of our personal selves, but immortality realized through The Unborn. This requires an expansion of our scope and the empathy and understanding to see The Unborn in union with, and equals of, ourselves. We are a part of something eternal that stretches back to the beginning of time and out into the limitless future.

In Vineland, it is Sasha, Frenesi’s mother, who is shown to have the greatest Moral and Vertical Memory. As an old Hollywood communist, she is a living connection to a radical past that Reagan’s Time War is eager to eliminate. She is also the direct descendent of Against the Day’s Traverse family, who participated in the all-but-forgotten labor movements of the turn of the century. Her father, Jess Traverse, escaped the Ludlow Massacre, in which the Colorado National Guard opened fire on a striking miners’ camp, and killed more than twenty people, including women and children. This massacre was orchestrated, in part, by John D. Rockefeller, Jr, and goes unspoken in the telling of the history of the United States, as do almost all labor struggles. American history is taught as a series of isolated events, little pearls strung along time’s arrow, but that’s presentism’s lie.

Only The Dead can remind us that things didn’t have to turn out this way; that, indeed, there were people who gave their lives trying to make it otherwise; that the arc of the universe only bends when there are people willing to put their shoulder to it. The Traverse family has maintained these hidden connections. They keep their allegiance to the past and the future alive through their huge, annual family gatherings. All of this gives Sasha a feeling of purpose that is largely missing from not only her daughter, but much of the sixties counter culture, who have sworn off the immediate past and been cut off from anything deeper.

We Are Pynchon’s Fail Sons and Thot Daughters

False starts and dead ends have been the history of the North American left. It’s not that it has simply failed to maintain a connection to its past, but that that connection has been purposely shattered, again and again. Eugene V. Debs, the most popular socialist candidate in American history, was jailed for sedition, and still received a million votes. State- and capital-backed assassinations have brought down popular leaders, from Frank Little, to Joe Hill, to the Rosenbergs and Fred Hampton, and up till the leaders of the Ferguson Uprising.

Beyond that, compromises have been made. Improved technology and ridiculous surplus meant the generations following those striking miners were allowed new comforts. The New Deal bought off revolutionary fervor in exchange for middle class comfort, at least for many white Americans.

“Roosevelt understood that there is no lasting solution to capitalism’s contradictions and that they can only be temporarily mitigated. As the state’s top executive, his task was to bring to bear his considerable political acumen to stabilize the capitalist crisis and prevent a socialist revolution. Along with the police and National Guard, he leaned on the AFL’s lick-spittle compromisers, as he skillfully exploited the divisions within the workers’ mass organizations. The class struggle was heating up, and between 1932 and 1933, the number of strikes doubled. Roosevelt had to act” (Goodman).

The flower children of the revolutionary sixties grew up in the bosom of New Deal America. They were largely raised in these middle class families that had comfortable lives in the suburbs. It may have been these very lives of consumer conformity that first lit their rebellious nature, but their ideological roots were shallow. Put another way, The Dead are theory and The Living praxis. One without the other won’t get you very far. They were cut off from the flow of history, and thus stunted, fighting without the bone-deep conviction needed to face down empire.

Young Frenesi struggles to even believe in the reality of her world. The screen and the camera feel more real than life. And throughout the novel, we see characters seemingly trying to enact their roles through tropes seen in movies: mafia members acting like mafia movies, ninjas acting like ninja movies, hippies acting like movie hippies, etc.

In the sixties, Frenesi’d been a member of a counter-cultural film crew known as 24fps, who in one scene is having an argument about lighting, speaking in the way familiar to any who have spent time around an undergrad film set will recognize. “Film equals sacrifice” type shit. But then, in an internal monologue, Frenesi wonders if she believes even that. “Did she really believe that as long as she had it inside her Tubeshaped frame, soaking up liberated halogen rays, nothing out there could harm her?” (202).

Caught between life and the camera, both become unreal, and she is not the only one to feel that sneaking irreality. Takeshi points out something similar later on,

“We are assured by the Bardo Thodol, or Tibetan Book of the Dead, that the soul newly in transition doesn’t like to admit—indeed will deny quite vehemently—that it’s really dead, having slipped so effortlessly into the new dispensation that it finds no difference between the weirdness of life and the weirdness of death, an enhancing factor … being television, which with its history of picking away at the topic with doctor shows, war shows, cop shows, murder shows, had trivialized the Big D itself. If mediated lives, he figured, why not mediated deaths?” (218).

Brock Vond’s bread and butter was understanding the true dynamic of these college student revolutionaries. He is able to see the weakness at the root of the movement, infiltrate it, and play its members against each other, to great success:

“[His] genius was to have seen in the activities of the sixties left not threats to order but unacknowledged desires for it. While the Tube was proclaiming youth revolution against parents of all kinds and most viewers were accepting this story, Brock saw the deep—if he’d allowed himself to feel it, the sometimes touching—need only to stay children forever, safe inside some extended national family. The hunch he was betting on was that these kid rebels, being halfway there already, would be easy to turn and cheap to develop. They’d only been listening to the wrong music, breathing the wrong smoke, admiring the wrong personalities. They needed some reconditioning” (269).

And he is not entirely wrong. While there were real revolutionary actions occurring in the sixties, such as the anti-Vietnam War effort and the black liberation movement, a fictional contingent of which (Black Afro-American Division (or BAAD)) visits the hippie counter culture who is occupying a campus where they have formed a sort of temporary autonomous zone known as The People’s Republic of Rock and Roll. PR3, in its search for allies, reaches out to BAAD who sends a small party to the seaside campus. BAAD’s arrival cuts a stark difference between themselves and the hippie students. Their discipline and commitment to the movement is immediately evident, for they arrive wearing matching uniforms of “Shiny black Vietnam boots, black-on-black camo fatigues, and velvet-black berets with off-black wide-point stars on them” (230).

BAAD enters into a long debate with the students, who they brush off as “children of the surfing class” (230), that is to say, unserious. The New Deal, one suspects, was quite purposefully not for everyone. It successfully played on race divisions, a favorite move by the good ol’ US of A, by elevating the white working class to a new level of comfort and security, while leaving everyone else to fend for themselves.

BAAD sees the students as cos-players rather than revolutionaries. They laugh off the idea that they are on the same side, saying “The Man’s gun don’t have no blond option on it” (231), and in the end they leave with the keys to a Porsche 911, given over by Rex, one of the most outspoken members of PR3, in a desperate effort to prove his radicality.

Rex is a perfect example of the brittleness of this children of the surfing class revolution, as Vond shortly thereafter uses him as a pawn to kill the accidental leader of the movement, one Weed Atman, proving his notion that they can be bought off on the cheap. This proves true, also, with Frenesi who not only turns fink and sets up Weed, setting off the chain of events that lead to Rex killing him, but she also enters into one of Pynchon’s many sado-sexual relationships with authority when she starts fucking Brock Vond.

The Trillbillies identify this recurring theme of leftist women lusting after fascist men in their episode on Bleeding Edge where a similar relationship occurs between Maxine and Windust, and again in Against the Day, and it’s all over Gravity’s Rainbow. While they joke that maybe Pynchon just has a cuck fetish, they eventually decide it is meant more metaphorically6.

“I think it’s kind of like a biblically inspired thing…the prophet Ezekiel compares Jerusalem to a harlot that has gone astray from God…I think we can question how in good taste this metaphor is, but thinking of it as a metaphor…it’s hard to disagree that America has many times committed adultery against itself in the sense that America says that it is trying to be for freedom and equality and all these lofty goals and basically every generation America is…betraying itself…America has these instincts to be good, but then instead it…lets the worst, greediest people take over.”

In the end, this movement is doomed to fail because it is caught in the same crystalized presentism as that which they are meant to be rebelling against. They have no connection to the past, and, caught as they are in that arrested development desire to “remain children forever”, they have abandoned any future beyond themselves as well. They are largely content to be bought off; to funnel their rebellious energies into consuming counter cultural products, something They will readily provide, because their is nothing They love more than a new revenue stream.

Let the children grow their hair and listen to loud music, throw protests and sing kumbaya. The boot only comes down when you get too close to the money, as we saw last year with the brutal retaliation against the Columbia encampments.

The movement of the sixties’ collapse is not totally due to betrayal, however. Zoyd, proudly, never turns informant, and is eventually awoken to The Living’s responsibility to The Unborn by his sick daughter’s looking up to him and asking “Am I ever going to feel bettor?”

Of course entering into an alliance with The Unborn is not merely a plea for procreation, but rather a belief that the future is just as deserving of existence as those who just so happen to be walking around at this moment, and that maybe the planet and social structures should be treated in accordance with such a belief.

There are, also, those keeping up their end of the bargain with The Dead, such as D.L. who is trained by the Kunoichi as a kind of ninja and eventually sent to Japan and used by the mafia to carry out a mission meant to assassinate Brock Vond using a special technique known as the Vibrating Palm, which requires just a touch, and can be temporally delayed so that the victim might live on up to a year before finally subsuming to the death touch. Vond, however, becomes privy to danger and sends in someone else in his stead, which is how Takeshi receives the touch, and begins desperately seeking an antidote, which brings him to California and the Kunoichi Dojo, where he receives treatment, and D.L. is assigned to assist him for a year in order to atone for her mistake.

Together they set up a Karmalogy Clinic meant to help the Thanatoid community address “injustices not only from the past but virulently alive in the present day”, and they end up helping Prairie address the injustices done to her by helping to organize a mother-daughter reunion right under Brock’s nose.

There is no saving the day, of course. This is a Pynchon novel. On the grand scale, nothing changes. Reagan’s reign will last the rest of the decade. The comforts of the New Deal will continue to be trimmed while revolutionary fervor is repressed in new and exciting ways, including, but not limited to mass surveillance and the deluge of television, film, and eventually the internet. Still, those connections to the past and future are being maintained by small enclaves despite all this. Living room shrines send up incense smoke, calling forth the dead. Deadbeat Zoyd becomes a caring father. The Karmalogy Clinic continues its underground work.

I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to eliminate bindweed from your yard, but it is a notoriously stubborn vine. Rip out its growths and it survives hidden in its vast root system that extends beyond what the limits of private property will allow you to get at. New shoots will continuously be sent forth like an endless game of Whack-a-Mole. Such a vine can only be repressed for so long. Eventually it overwhelms.

{Exit Music]

The meat of the novel is derived out of the messiness of the lives and deaths of Pynchon’s most fleshed-out characters to date, at least at the time of this book’s publication, which is why I find it surprising that David Foster Wallace, that big New Sincerity sap, famously discarded it, writing in a letter to Johnathan Franzen, “I get the strong sense he [Pynchon] spent 20 years smoking pot and watching TV.”

A book alluded to by the novel’s present taking place in 1984.

From thanato-: “death”; and -oid: “resembling”.

Karma is probably the most cited Buddhist concept in popular culture, but it is one that has been drastically vulgarized. Pynchon gets a lot of gas out of California’s bastardization of Buddhism, from Bodhi-Dharma Pizza Temple’s nigh-on inedible hippie pies to the Sisterhood of Kunoichi Attentives, an all-female ninja dojo hidden in the forests of California. Still, one cannot escape the feeling that this is not simple cultural appropriation by California yuppies, but a desperate groping for some kind of meaning in an increasingly meaningless America.

at least in the Marseille edition.

Though this doesn’t get him off the hook for the number off footjobs that occur across his oeuvre.

(Joey from WAC here . . . ) Pynchon was working with a lot of the themes/ ideas/ archetypes we've all been scrambling to bring into digital-era relevance (mostly unsuccessfully). I think DFW came the closest with Infinite Jest, but that doesn't discredit TP for his post-beat/pre-internet prescient contributions. "You (. , ; etc.) never did (. , ; etc.) the Kenosha Kid (. , ; etc.)" AI can't even do Flarf! (although, I'm trying to teach it . . .)

Great read, thanks.